If I were to pick one band to illustrate the convoluted rock trends of the 1980’s, it would be The Cult. This notoriously fractious, unpredictable, and peripatetic band usually hovered somewhere in between the Doors and AC/DC in its overall sound, but ventured into all sorts of other moods. Despite their notorious internal bickering and temporary split-ups, they have managed to remain a force in rock for a quarter century. Anyone with a serious rock collection is likely to own copies of Love (my own favourite) and Sonic Temple. Their Canadian tour last year still pulled in huge crowds, especially here in Toronto. During one of their temporary split-ups, lead singer Ian Astbury started up a garage band called Holy Barbarians, which recorded only this one album, in 1999. Cream is a decent album, worth playing now and then, but it illustrates how much The Cult benefited from the fine guitar playing of Billy Duffy. Without him to balance Astbury, the singer often comes across too heavy-handed. Some of the songs seem stagy and melodramatic. But “Opium” is first rate, and “Brother Fights” is quite good, too. If you are a Cult fan, pick up this album, not only for the sake of completeness, but to show, by contrast, just how the combination of Duffy and Astbury worked.

Category Archives: CO - Listening 2007 - Page 2

First-time listening for September, 2007

17575. The Music of Islam: Volume 1 — Al Qahirah [Music of Cairo]

17576. (Maurice Ravel) Sérénade grotesque

17577. (Maurice Ravel) Valses nobles et sentimentales

17578. (Thelonius Monk) Thelonius Monk with John Coltrane — The Complete April-July 1957

. . . . . Recordings

17579. (Cowboy Junkies) The Caution Horses

17580. (Wilhelm Stenhammar) Snöfrid, Op.5

17581. (Wilhelm Stenhammar) Mellanspel ur kantaten “Sången”, Op.44

Read more »

Marie-Élaine Thibert

Marie-Élaine Thibert is a Montreal singer with a strong voice, which is reminiscent of Barbara Streisand’s. She first came to public attention when she belted out Jacques Brel’s technically difficult song “La quête”, on Quebec’s major talent show, Star Académie. The stadium-show-tunes kind of stuff is not really my kind of music, but I can appreciate the talent here. Quebec seems to grow highly professional mainstream singers as easily as British Columbia grows marijuana. There seems to be an endless supply. But only a few of them, such as Céline Dion, break out into the rest of the world. On the strength of this album, which has confident showmanship, I would guess that she will make it out, probably first in Europe. I haven’t heard all her second album, Comme ça, but it has a hit in a cover of Monique Leyrac’s old standard “Pour cet amour”, a duet with Chris deBurgh (a translation of “Lonely Sky”), and a very fine, subtle song I’ve heard online, “Les herbes hautes”.

Marie-Élaine Thibert is a Montreal singer with a strong voice, which is reminiscent of Barbara Streisand’s. She first came to public attention when she belted out Jacques Brel’s technically difficult song “La quête”, on Quebec’s major talent show, Star Académie. The stadium-show-tunes kind of stuff is not really my kind of music, but I can appreciate the talent here. Quebec seems to grow highly professional mainstream singers as easily as British Columbia grows marijuana. There seems to be an endless supply. But only a few of them, such as Céline Dion, break out into the rest of the world. On the strength of this album, which has confident showmanship, I would guess that she will make it out, probably first in Europe. I haven’t heard all her second album, Comme ça, but it has a hit in a cover of Monique Leyrac’s old standard “Pour cet amour”, a duet with Chris deBurgh (a translation of “Lonely Sky”), and a very fine, subtle song I’ve heard online, “Les herbes hautes”.

The Death of Pavarotti

Well, there’s not much I can say about Pavarotti that others aren’t better qualified to say. He is one of those figures that steps out of a genre. People who hardly ever listen to jazz know Louis Armstrong, people who hardly ever listen to opera know Pavarotti, who successfully stepped into the shoes of Caruso as the ambassador of opera to the broad public. He fulfilled the role brilliantly, using his comical, un-threatening appearance to advantage. It was as if your favourite jolly uncle had super-powers, which he only used after dinner. On hearing of his death, I played his wonderful duet with James Brown, and his rather peculiar one with Lou Reed. Then I went through Pavarotti’s Greatest Hits, with his famed arias from Rigoletto and L’élisir d’Amore, among others. Then I played his album of Neapolitan folk songs, O Sole Mio, and his album of Christmas carols, O Holy Night. Over the course of the next two days, I played a few entire operas in which he starred: Bellini’s Beatrice di Tenda, and I Puritani, where he sang with Joan Sutherland, one of the few women with the stature and lung power to stand up to him in the ring; as well as an early performance of Puccini’s La Bohème, with Freni, directed by von Karajan.

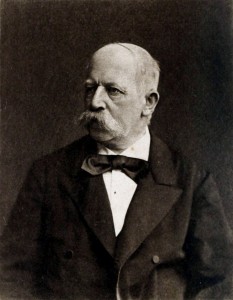

Robert Volkmann

Ten years ago, CBC radio broadcast Robert Volkmann’s Symphony #1 in D. I was charmed by it. The announcer said that it sounded like “a forgotten work by Brahms”. True enough, and Volkmann’s obscurity could easily be explained by saying he was one of Brahms’ many imitators. But that symphony was composed in 1862, and Brahms’ first symphony didn’t appear until fourteen years later. I’ve never been able to find a copy of that symphony, and didn’t hear the whole thing on the CBC broadcast, so it isn’t listed in my listening files. But I have obtained two works by him, the Konzertstück for Piano & Orchestra, and the Cello Concerto. Both are entertaining and well-crafted, but not overwhelming. The cello concerto is worth several listens. Both works reveal his real influence: Schumann. Volkmann lived from 1815 to 1883. He was born in Saxony, spent a short stint in Prague, then the rest of his life in Budapest. He was respected and often played in his lifetime, but fell out of the repertory after his death. It’s more fair to say that he was a serious composer whose work followed on Schumann and anticipated Brahms, whom he influenced significantly. This is not dismissible as mere imitation. But time has a way of casting off such in-betweens.

Ten years ago, CBC radio broadcast Robert Volkmann’s Symphony #1 in D. I was charmed by it. The announcer said that it sounded like “a forgotten work by Brahms”. True enough, and Volkmann’s obscurity could easily be explained by saying he was one of Brahms’ many imitators. But that symphony was composed in 1862, and Brahms’ first symphony didn’t appear until fourteen years later. I’ve never been able to find a copy of that symphony, and didn’t hear the whole thing on the CBC broadcast, so it isn’t listed in my listening files. But I have obtained two works by him, the Konzertstück for Piano & Orchestra, and the Cello Concerto. Both are entertaining and well-crafted, but not overwhelming. The cello concerto is worth several listens. Both works reveal his real influence: Schumann. Volkmann lived from 1815 to 1883. He was born in Saxony, spent a short stint in Prague, then the rest of his life in Budapest. He was respected and often played in his lifetime, but fell out of the repertory after his death. It’s more fair to say that he was a serious composer whose work followed on Schumann and anticipated Brahms, whom he influenced significantly. This is not dismissible as mere imitation. But time has a way of casting off such in-betweens.

First-time listening for August, 2007

17498. (Gustav Mahler) Das Klagende Lied [s. Shaguch, DeYoung, Moser, Leiferkus]

17499. (Illuminati) The Illuminati [with bonus bootlegs]

17500. (Alan Hovhaness) Symphony #24, Op.273 “Majnun”

17501. (Oscar Peterson) Oscar Peterson Plays Duke Ellington

17502. Otantic Azerbaycan Reksleri 2: Music of Azerbaijan

17503. (Frederick Delius) A Walk to the Paradise Garden

17504. On Marco Polo’s Road: The Musicians of Kunduz and Faizabad

17505. (Robert Volkmann) Konzertstück for Piano and Orchestra, Op.42

Read more »

Harry Somers’ Songs

Harry Somers (1925–1999) was probably the most respected composer in Toronto during his generation. The serialist John Weinzweig found him composing, self-taught, as a teenager, and encouraged him to train vigorously in both traditional harmony and in avant-garde twelve-tone techniques. He ended up training under the fairly conservative French composer, Darius Milhaud. In the end, he settled on an eclectic style. Up until now, all I’ve listened to closely was his justly popular Five Songs from Newfoundland Outports. But today, I listened to a collection of his songs, both secular and sacred, by the Elmer Isler Singers. I was surprised at their combination of sassy humour — “Spotted Snakes” is the best example of that — and lyrical beauty. The “Three Songs of New France” are really fine, quite as good as the famed Newfoundland set. The sacred pieces combine conventional reverence with some unconventional twists. I particularly like “God The Master of This Scene” and “Bless’d Is the Garden of the Lord”. There’s a touch of Messiaen in these, but in a clean-cut, wholesome Toronto boy way. Canadian composers, even when they see themselves as bad boys, tend to be polite and well-scrubbed behind the ears. It’s our kismet.

Utopia Triumphans and Tallis’ Spem In Alium

The Huelgas Ensemble, under the direction of Paul Van Nevel, put together a collection of Renaissance polyphonic works for large choirs, which they called “Utopia Triumphans”. In fact, these works are for huge choirs. It starts with Thomas Tallis’ astonishing 40-part motet Spem in alium, and ends with Alessandro Striggio’s 40-part Ecce beatam lucem. Striggio’s piece was performed in England in 1567, and caused such a stir that it was taken as a challenge. It is said that Tallis was commissioned to compose an “answer”, and Spem in alium was the result (however some authorities doubt this story).

The Huelgas Ensemble, under the direction of Paul Van Nevel, put together a collection of Renaissance polyphonic works for large choirs, which they called “Utopia Triumphans”. In fact, these works are for huge choirs. It starts with Thomas Tallis’ astonishing 40-part motet Spem in alium, and ends with Alessandro Striggio’s 40-part Ecce beatam lucem. Striggio’s piece was performed in England in 1567, and caused such a stir that it was taken as a challenge. It is said that Tallis was commissioned to compose an “answer”, and Spem in alium was the result (however some authorities doubt this story).

Motets on this scale are very difficult to mount. The manuscript kicked around for centuries, but no doubt those who looked at it shrugged their shoulders. Interesting, but too much work to put on, and Tallis had little selling power. His reputation was eclipsed by his pupil William Byrd, and if Ralph Vaughan Williams had not composed his Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis, few would have heard his name. But in 1965, the choir of King’s College Cambridge took a chance, and recorded it. Subsequently, there was a revival of interest in Tallis, and today I noticed a site listing it among the “top 10 essential choral pieces”. There have been many recordings of it, the most well known being that of the Tallis Scholars. Perhaps the most amazing tribute to the work is in the National Gallery of Canada, in Ottawa. Here, Maya 3D modeling software, laser scanning and photogrammetry were used to accurately recreate the interior of a beautiful convent chapel which, unfortunately, had to be demolished. Within this model (where even the “sunlight” in the stained glass is artificial), forty speakers set around the chapel each play the sound of a single voice of the forty-part choir, allowing for an especially intense, and variable experience of the piece. Read more »

First-time listening for July, 2007

17395. (Aztec Camera) Stray

17396. (Johannes Brahms) Piano Trio #1 in B, Op.8

17397. (Johannes Brahms) Piano Trio #2 in C, Op.87

17398. (Johannes Brahms) Piano Trio #3 in C Minor, Op.101

17399. (Johannes Brahms) Piano Trio #4 in A, Op. Posth.

(Homayun Sakhi) The Art of the Afghan Rubâb:

. . . . 17400. (Homayun Sakhi) Raga Madhuvanti

. . . . 17401. (Homayun Sakhi) Raga Yaman

. . . . 17402. (Homayun Sakhi) Kataghani

17403. (Karol Szymanowski) Violin Concerto #1, Op.35

Read more »

Sandy Scofield

One of the finest singers in Western Canada, Sandy Scofield glides effortlessly from her Métis and Cree musical roots into a high-level synthesis of jazz, blues, rock and pop. Long known in aboriginal music circles, she deserves to break out into the global music scene. Her music is original, refined, and intelligent. I possess three of her four albums, Dirty River (1994), Riel’s Road (2000), and Ketwam (2002). I have yet to hear all of this year’s release, Nikawiy Askiy, but I’ve heard three songs from it, and they clearly indicate that her musical evolution is continuing without hindrance. Riel’s Road is probably the best introduction to her work, opening with the stunning “Beat the Drum (Gathering Song)”, and going on to explore emotionally the aftermath and consequences of the most dramatic events in post-Confederation Canada’s history, the Métis uprising and death of Louis Riel. However, most of the songs on this album have a folk-jazz feeling. On Ketwam, which focuses on much more traditional aboriginal-métis material, she collaborates with the vocal trio Nitsiwakun, of which she is one member (the other two are Lisa Sazama and Shakti Hayes), with fiddle Daniel Lapp, and with vocalist Winston Wuttunee. The Cree-language songs are the most powerful. The album is truly collaborative. Some are the finest moments belong to Hayes on “Nitsimos” and to “Wuttunee” on “Tapweh” (a traditional round dance that would fit in at any western powow).