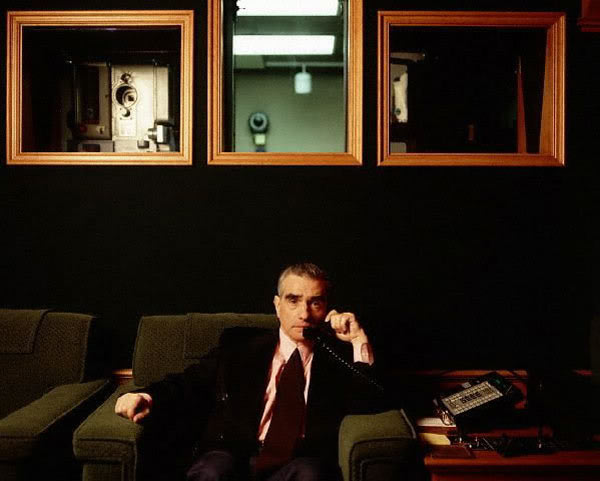

Scorsese is a highly cultured, literate and civilized man, without pretension and remarkably free of snobbery. In this study of the American films that entertained and influenced him, he opens our eyes to the artistry of many Hollywood films ― westerns, gangster films, musicals, and low-budget thrillers ― that film historians and critics would sneer at. This four hours long documentary undermines that obnoxious tendency in all the arts, the glorification of an official canon of “classics”. His analysis of films by forgotten and underrated directors is sharp, but affectionate.

Scorsese is a highly cultured, literate and civilized man, without pretension and remarkably free of snobbery. In this study of the American films that entertained and influenced him, he opens our eyes to the artistry of many Hollywood films ― westerns, gangster films, musicals, and low-budget thrillers ― that film historians and critics would sneer at. This four hours long documentary undermines that obnoxious tendency in all the arts, the glorification of an official canon of “classics”. His analysis of films by forgotten and underrated directors is sharp, but affectionate.

Category Archives: D - VIEWING - Page 28

(Scorcese & Wilson 1995) A Personal Journey With Martin Scorsece Through American Movies

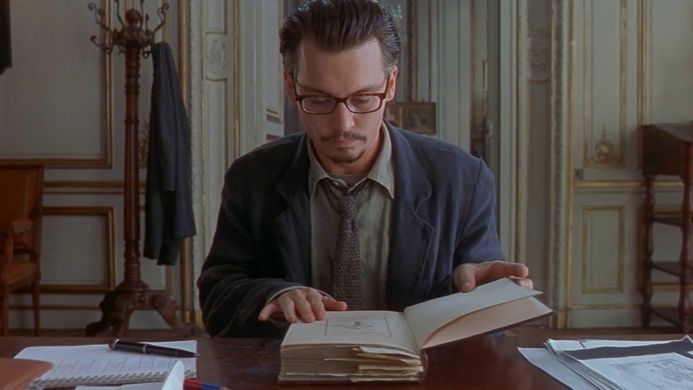

(Polanski 1999) The Ninth Gate

I don’t understand what motivated Polanski to make this muddled supernatural thriller. It’s the sort of thing that works fine in a book, but makes a terrible movie. You can sort of guess what is going on at the end, but doubtless most of the audience left the theatres scratching their heads. A pity, because Johnny Depp’s performance is, as usual, extremely professional. He wrings as much out of the emotionally ambiguous character as he can. Most of us who love books would have been charmed to see an entertaining film in which rare book collectors and dealers are given a fictional life involving murder, intrigue, and hot sex, however inaccurately the technical details of book collecting are presented. But this film doesn’t entertain. Half-way through, one becomes bored with the enigmas, sensing, correctly, that they will not lead to any interesting conclusion.

I don’t understand what motivated Polanski to make this muddled supernatural thriller. It’s the sort of thing that works fine in a book, but makes a terrible movie. You can sort of guess what is going on at the end, but doubtless most of the audience left the theatres scratching their heads. A pity, because Johnny Depp’s performance is, as usual, extremely professional. He wrings as much out of the emotionally ambiguous character as he can. Most of us who love books would have been charmed to see an entertaining film in which rare book collectors and dealers are given a fictional life involving murder, intrigue, and hot sex, however inaccurately the technical details of book collecting are presented. But this film doesn’t entertain. Half-way through, one becomes bored with the enigmas, sensing, correctly, that they will not lead to any interesting conclusion.

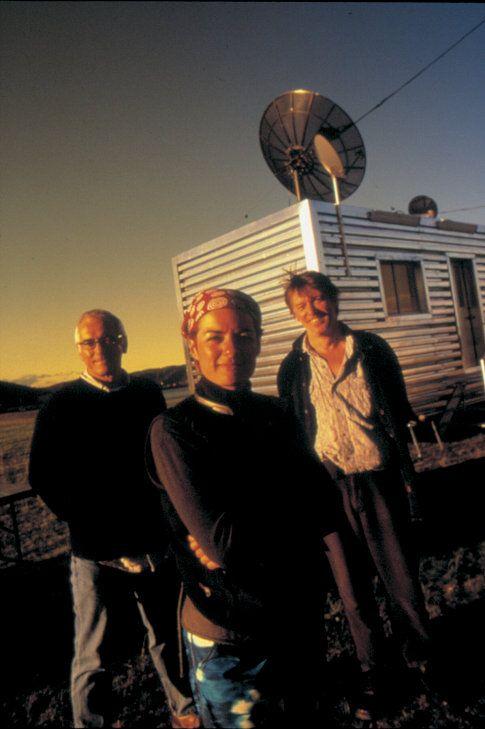

(Briand 2002) La Turbulence des Fluides

I rather like this attempt at a Shyamalanesque thriller by director Manon Briand. Unfortunately, it’s way too slow-moving to satisfy a big audience, and it telegraphs its ending. It focuses on a seismologist, long exiled to Japan, who returns to the town of her birth, Baie-Comeau (on the remote North Shore coast of Quebec) to investigate some anomalies. The town is haunted by the death of a woman in a freak accident, and is full of psychological, as well as physical anomalies. While the film is weak as drama, it is delightful visually and sensually. Both the heroine, Alice Bradley (played by Pascales Buissière) and her jealous lesbian friend (played by Julie Goyet) are extremely beautiful.

I rather like this attempt at a Shyamalanesque thriller by director Manon Briand. Unfortunately, it’s way too slow-moving to satisfy a big audience, and it telegraphs its ending. It focuses on a seismologist, long exiled to Japan, who returns to the town of her birth, Baie-Comeau (on the remote North Shore coast of Quebec) to investigate some anomalies. The town is haunted by the death of a woman in a freak accident, and is full of psychological, as well as physical anomalies. While the film is weak as drama, it is delightful visually and sensually. Both the heroine, Alice Bradley (played by Pascales Buissière) and her jealous lesbian friend (played by Julie Goyet) are extremely beautiful.

(Low 1988) Beavers

It may come as a surprise to film buffs, but Stephen Low’s 1988 documentary film about the life of a family of beavers in Alberta is the most successful Canadian film of all time. With a budget of one million dollars, it grossed over 80 million playing in 230 IMAX theatres. Low’s Montreal-based production company has produced most of the top IMAX format films. His much more recent film, Volcanoes of the Deep Sea, was not run in many U.S. theatres because it contains references to Evolution (yes, rub your eyes and gasp, but that is the level of imbecility that things have sunk to, there). Now, nothing could be more quintessentially Canadian than a documentary about Our Friend the Beaver ― we all had to endure them repeatedly in grade school. Beaver documentaries are probably the equivalent for Canada of the Western for Hollywood, and the samurai epic for Japan. But nothing prepared me for this. The film is brilliant. It is powerful, emotional, moving. It is inspiring. It is beautiful. The cinematography is brilliant. Some of the shots, if they had been devised by Kubrick or Fellini, would be studied in film schools. The composition, colour, and editing are superb. And the acting, by beavers who are apparently professionals trained at Stratford, is top-notch. The love scene, with young amorous beavers dancing in the moonlight, is among the most romantic ever filmed.

It may come as a surprise to film buffs, but Stephen Low’s 1988 documentary film about the life of a family of beavers in Alberta is the most successful Canadian film of all time. With a budget of one million dollars, it grossed over 80 million playing in 230 IMAX theatres. Low’s Montreal-based production company has produced most of the top IMAX format films. His much more recent film, Volcanoes of the Deep Sea, was not run in many U.S. theatres because it contains references to Evolution (yes, rub your eyes and gasp, but that is the level of imbecility that things have sunk to, there). Now, nothing could be more quintessentially Canadian than a documentary about Our Friend the Beaver ― we all had to endure them repeatedly in grade school. Beaver documentaries are probably the equivalent for Canada of the Western for Hollywood, and the samurai epic for Japan. But nothing prepared me for this. The film is brilliant. It is powerful, emotional, moving. It is inspiring. It is beautiful. The cinematography is brilliant. Some of the shots, if they had been devised by Kubrick or Fellini, would be studied in film schools. The composition, colour, and editing are superb. And the acting, by beavers who are apparently professionals trained at Stratford, is top-notch. The love scene, with young amorous beavers dancing in the moonlight, is among the most romantic ever filmed.

And it’s a documentary about beavers.

Honest. I kid you not.

(Kapur 1998) Elizabeth

Why on earth was this nominated for Best Picture in its year? It’s glossy, and could be reasonably entertaining to someone who does not know what a travesty of history it is, but it isn’t a particularly outstanding film. The contest between Catholicism and Protestantism during the Reformation (in which both sides were relentlessly fanatical and vicious), is still played out in English film and literature to this very day. This particular film is pretty obvious in its partisanship: Protestantism (symbolized by Elizabeth) is good and Catholicism is bad. In England, there is still a kind of anti-Catholic sentiment which is played out in cartoon form in films such as this. Every cliché is there. Foreign Catholic priests skulk around in the shadows with sinister, swirling robes, and look like demons. A French nobleman is a screaming fag, mincing about. Elizabeth spouts anachronistic sentiments of selfless patriotism and “individual conscience”. Her executions and persecutions are explained away as unfortunate zeal by subordinates, or understandable reactions to treachery, or necessary steps in a grand plan to build the future glories of England (cue the Elgar marches). Essex doesn’t really mind having his head chopped off — it’s all part of true love. Mary Queen of Scots is mentioned, briefly, but there’s no follow up. Such side-taking is common enough, and there are pro-Catholic interpretations that are every bit as silly. But in this film, historical facts are so grossly misrepresented that no amount of acting or costume splendour can make it worth watching without belly laughs. Siskel & Ebert loved this film, but I don’t think they paid much attention in high school history class.

Why on earth was this nominated for Best Picture in its year? It’s glossy, and could be reasonably entertaining to someone who does not know what a travesty of history it is, but it isn’t a particularly outstanding film. The contest between Catholicism and Protestantism during the Reformation (in which both sides were relentlessly fanatical and vicious), is still played out in English film and literature to this very day. This particular film is pretty obvious in its partisanship: Protestantism (symbolized by Elizabeth) is good and Catholicism is bad. In England, there is still a kind of anti-Catholic sentiment which is played out in cartoon form in films such as this. Every cliché is there. Foreign Catholic priests skulk around in the shadows with sinister, swirling robes, and look like demons. A French nobleman is a screaming fag, mincing about. Elizabeth spouts anachronistic sentiments of selfless patriotism and “individual conscience”. Her executions and persecutions are explained away as unfortunate zeal by subordinates, or understandable reactions to treachery, or necessary steps in a grand plan to build the future glories of England (cue the Elgar marches). Essex doesn’t really mind having his head chopped off — it’s all part of true love. Mary Queen of Scots is mentioned, briefly, but there’s no follow up. Such side-taking is common enough, and there are pro-Catholic interpretations that are every bit as silly. But in this film, historical facts are so grossly misrepresented that no amount of acting or costume splendour can make it worth watching without belly laughs. Siskel & Ebert loved this film, but I don’t think they paid much attention in high school history class.

(Menzies 1936) Things To Come

H. G. Wells participated directly in this pioneer Science Fiction film of 1936. The film is visually fascinating. No expense or effort was spared in it’s art direction, to put across the 1930’s vision of the future, with it’s moving sidewalks and colossal shoulder-pads. It is also imbued with the totalitarian atmosphere of that era. Wells envisions a world war coming (he places it in 1940), which drags on for decades until the world is reduced to barbarism. Then a technocratic force of scientist-airmen takes over the world and builds it into a “utopia”. It is all white walls and glass tubing. One character explains that their savage ancestors lived “half-out-doors” before they learned the superiority of artificial light. Finally, in 2036 AD, an expedition is sent to the Moon, despite the attempt of an “anti-progress” artist to sabotage the project. Read more »

H. G. Wells participated directly in this pioneer Science Fiction film of 1936. The film is visually fascinating. No expense or effort was spared in it’s art direction, to put across the 1930’s vision of the future, with it’s moving sidewalks and colossal shoulder-pads. It is also imbued with the totalitarian atmosphere of that era. Wells envisions a world war coming (he places it in 1940), which drags on for decades until the world is reduced to barbarism. Then a technocratic force of scientist-airmen takes over the world and builds it into a “utopia”. It is all white walls and glass tubing. One character explains that their savage ancestors lived “half-out-doors” before they learned the superiority of artificial light. Finally, in 2036 AD, an expedition is sent to the Moon, despite the attempt of an “anti-progress” artist to sabotage the project. Read more »

(Franklin 1995) Devil in a Blue Dress

I just recently discovered the fiction of Walter Mosley [see review of “47”]. I haven’t yet read any of his “Easy Rawlins” series of mysteries, but I just saw this film,.made from the first one. Why hadn’t I heard of this film? It’s a superb Chandleresque thriller, with fine acting in every role. The scenes between Denzel Washington and Don Cheadle are particularly fine. The setting, Los Angeles in the 1940’s, when thousands of African-Americans had recently migrated from the Deep South to work in the aircraft plants, is meticulously recreated.

I just recently discovered the fiction of Walter Mosley [see review of “47”]. I haven’t yet read any of his “Easy Rawlins” series of mysteries, but I just saw this film,.made from the first one. Why hadn’t I heard of this film? It’s a superb Chandleresque thriller, with fine acting in every role. The scenes between Denzel Washington and Don Cheadle are particularly fine. The setting, Los Angeles in the 1940’s, when thousands of African-Americans had recently migrated from the Deep South to work in the aircraft plants, is meticulously recreated.

(Curtiz & Keighley 1938) The Adventures of Robin Hood

It’s doubtful that anyone will ever match the charm that Errol Flynn brought to the role of Robin Hood in 1938. The film still holds up well as an entertaining adventure, after 68 years. It helps that it was done in the superb colour process of that era — better, but more expensive, than the process used in the 1950’s and 1960’s. The Robin Hood tales are supposed to take place in the Twelfth Century, but they first appear in a series of folk ballads that emerged centuries after the time, though Piers Ploughman, written in 1370, refers to “the rhymes of Robin Hood”. The Robin Hood of the film, our Robin Hood, is essentially the one created by the Nineteenth Century children’s writer and (brilliant) illustrator, Howard Pyle. The film is fairly consistent with Pyle’s Robin. But for millions of people around the world Robin Hood will always be Errol Flynn, and the mythical hero of Britain incarnate in a roguish and ribald Tasmanian.

It’s doubtful that anyone will ever match the charm that Errol Flynn brought to the role of Robin Hood in 1938. The film still holds up well as an entertaining adventure, after 68 years. It helps that it was done in the superb colour process of that era — better, but more expensive, than the process used in the 1950’s and 1960’s. The Robin Hood tales are supposed to take place in the Twelfth Century, but they first appear in a series of folk ballads that emerged centuries after the time, though Piers Ploughman, written in 1370, refers to “the rhymes of Robin Hood”. The Robin Hood of the film, our Robin Hood, is essentially the one created by the Nineteenth Century children’s writer and (brilliant) illustrator, Howard Pyle. The film is fairly consistent with Pyle’s Robin. But for millions of people around the world Robin Hood will always be Errol Flynn, and the mythical hero of Britain incarnate in a roguish and ribald Tasmanian.

FILMS APRIL-JUNE 2006

(Leiner 2000) Dude, Where’s My Car?

(Scott 2005) Kingdom of Heaven

(Douglas 1954) Them!

(Lester 1966) A Funny Thing Happened On the Way To the Forum

(Armstrong 1999) MidSomer Murders: Ep.9 — Blood Will Out

(Page 2002) Into the Great Pyramid [documentary series]

(von Scherler Mayer 2002) Guru

Read more »