Those of us who admire a wild and irreverent spirit in music have long looked to Charles Ives (1874–1954) as our patron saint. With his multimetric chaos, his noisy brass bands, cheerful mixing of popular and classical themes, his temporal dyssynchronies and his startling flights into the infinite, he fulfilled every requirement for an eccentric genius ahead of his time. And he was profoundly, quintessentially American. But he was little known in his lifetime. The bulk of his compositions were written then tucked away, unperformed, in a New England barn while he pursued a more successful career as an insurance salesman. He also published pamphlets advocating what we would now call “direct democracy” and got into a heated argument with a young Franklin Roosevelt over his idea of promoting government bonds cheap enough for the ordinary citizen. But it was not until the 1960’s that his works were frequently played, and his name became familiar to classical musicians and listeners. Much of this change came about through the ardent advocacy of conductor Leonard Bernstein. It is possible to listen to a performance of Ives’ Symphony #4 today and experience it as “modern, avant-garde music” even though it was composed in the 1910s! (It wasn’t performed until 1965).

But fascinating as Ives is, he is not alone in the story of American music. Another composer, living a full century before him, shared many of Ives’ characteristics. Like Ives, he was self-taught, eccentric, experimental and ahead of his time. Like Ives, he wore his patriotism on his sleeve, loved loud noises and order disguised as chaos, and was drawn to transcendental themes. He died 13 years before Ives was born, and Ives probably never heard of him. Unlike Ives, however, he has found no high-profile champion. His works are played only occasionally and few people have heard them.

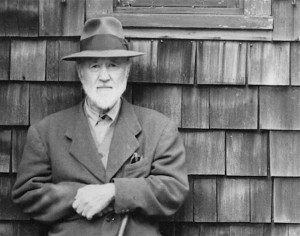

The man in question was Anthony Philip Heinrich. He was born in 1781, in the northernmost village of Bohemia, in what was then a predominantly German-speaking part of that land. Like Ives, he pursued a successful career as a businessman, relegating music to a hobby. But the Napoleonic wars ruined him, and he found himself penniless in Boston in 1810. He plunged into a new life enthusiastically, determined to be a wandering musician on the opening frontier. He traveled mostly on foot, living rough, through Pennsylvania, Ohio and Kentucky. This experience instilled in him a profound love of nature and an idealistic patriotism for his adopted country. Finally he settled in a log cabin in Kentucky and began to compose. America as yet had no real symphony orchestras and few trained musicians. His larger compositions could only be played in Europe. Eventually, he participated in founding the New York Philharmonic, and achieved some public success, but this quickly faded, and he died, reduced again to poverty, in 1861.

His music not only drew on American folk music and on the melodies and rhythms of Native Americans [Comanche Revel; Manitou Mysteries; The Cherokee’s Lament; Sioux Galliarde], but it was saturated with the signature element of American music: improvisation. Musicologists would no doubt classify him as his century’s most consistent practitioner of musical indeterminacy. Bird song filled his music, which often sported spectacularly grand ornithological titles: The Columbiad, or Migration of American Wild Passenger Pigeons and The Ornithological Combat of Kings. Perhaps the piece that sums him up is the vocal/orchestral suite, The Dawning of Music in Kentucky, or, the Pleasures of Harmony in the Solitudes of Nature. Nothing he composed followed the musical conventions of Europe. Altogether, I’ve heard 18 of his works, and all of them gave me pleasure, while some of them seemed to me both radical and profound. In other words, the qualities that drew me to Ives were present in Heinrich a century before.

It’s important, in this dark time for America, to remember that the nation that has sunk to the level of electing a scurrilous con-man, criminal and traitor to its highest office has in the past, over and over again, nurtured creative men and women imbued with the spirit of liberty, and will no doubt do so again. At this moment, I’m listening neither to Ives nor Heinrich, but to a country-rock album from 1968, The Wichita Train Whistle Sings. It’s by Mike Nesmith, remembered mostly as being one of television’s Monkees, but actually a man of varied talents. You can hear many elements of Heinrich and Ives bubbling through this almost, but not quite forgotten album. And they are bubbling in many works by singers, composers, garage bands, rappers, and electronic artists today. To use another Mike Nesmith album title: And the Hits Just Keep On Comin’.

0 Comments.