The extended blog entries called “Meditations” have proven to be the most popular items on this website. While some of these essays have some scholarly trappings (citations, etc.), they are primarily personal documents, and thus may contain colloquial prose, profanity, or other non-academic elements.

Anyone is entitled to reprint these pieces, as long as they are not altered, and credit is given.

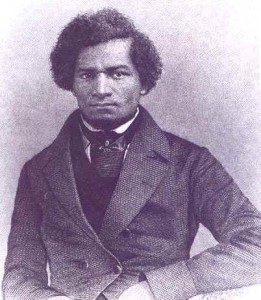

[Frederick Douglass (1818–1895), born a slave in Maryland, U.S.A., secretly taught himself to read, and successfully escaped slavery in 1838. His autobiography catapulted him to prominence in the anti-slavery movement. Widely known as the “Sage of Anacostia”, Douglass was the most prominent and influential African-American of his century, and one of the greatest philosophers of freedom in human history. In both word and deed, he struggled for the freedom and equality, not only of African-American males like himself, but for women, native Americans, immigrants, and all other human beings. One of his favorite quotations was: “I would unite with anybody to do right and with nobody to do wrong.”]

From A Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845):

Very soon after I went to live with Mr. and Mrs. Auld, she very kindly commenced to teach me the A, B, C. After I had learned this, she assisted me in learning to spell words of three or four letters. Just at this point of my progress, Mr. Auld found out what was going on, and at once forbade Mrs. Auld to instruct me further, telling her, among other things, that it was unlawful, as well as unsafe, to teach a slave to read. To use his own words, further, he said, “If you give a nigger an inch, he will take an ell. A nigger should know nothing but to obey his master–to do as he is told to do. Learning would spoil the best nigger in the world. Now,” said he, “if you teach that nigger (speaking of myself) how to read, there would be no keeping him. It would forever unfit him to be a slave. He would at once become unmanageable, and of no value to his master. As to himself, it could do him no good, but a great deal of harm. It would make him discontented and unhappy.” These words sank deep into my heart, stirred up sentiments within that lay slumbering, and called into existence an entirely new train of thought. It was a new and special revelation, explaining dark and mysterious things, with which my youthful understanding had struggled, but struggled in vain. I now understood what had been to me a most perplexing difficulty–to wit, the white man’s power to enslave the black man. It was a grand achievement, and I prized it highly. From that moment, I understood the pathway from slavery to freedom.

elsewhere, Douglas said:

To make a contented slave it is necessary to make a thoughtless one. It is necessary to darken the moral and mental vision and, as far as possible, to annihilate the power of reason.

From Thomas Paine’s The Rights of Man:

Man has no property in Man.

These meditations are constructed with a particular discipline. Every effort will be made to ensure that their terminology is consistent and meaningful. The reader will probably notice the conspicuous absence of some terms that are elsewhere accepted. The terms “capitalism” and “socialism”, for example, are not used anywhere because I consider them to be buzzwords without identifiable meaning. The terms “left” and “right”, supposedly representing a “political spectrum” of ideas and practice, have never been used in my work. This classification of political ideas is pernicious nonsense, and its use reduces any political discussion to incoherent gibberish. Instead, I will rely on a rational classification of political movements and ideas. The terms “West” and “Western”, along with their revealingly tendentious correlate “Non-Western”, are also renounced. They are embarrassing remnants of a narrow-minded past, still used with annoying imprecision and capriciousness. Worst of all, they came into use because of a profound misunderstanding of the world’s mosaic of societies. My reasons for these judgments will be expounded in an appendix to the Meditations.

Apart from this discipline, I’ll avoid creating an idiosyncratic jargon of my own. I prefer plain language. When I use a word or a phrase in some way that differs from general custom, or the reasonable expectations of readers, I will make every effort to make my meaning clear. However, language being a slippery thing, I can expect to fail at this now and then.

Works of serious thought are not written without an implied audience. The writer cannot avoid having some mental image, however vague, of who is likely to be reading their words. Often it can be easily recognized, for example, that a given writer assumes that the reader resides in their own country, or is of the same gender, or has a similar social or educational background. The more serious the subject matter, the more narrow this assumed audience is likely to be. Occasionally, a “we” or an “us” will appear in a work that makes it plain that the author assumes that “we” or “us” excludes most of the human race. This is not one of those works. It’s intended for all human beings, everywhere on the planet. If I had my druthers, I would prefer it to be simultaneously written in every language. Unfortunately, I can only write expressively and precisely in one language, English. Fortunately, that language is the world’s most widely distributed, and a work written in English can find it’s way into the hands of a diverse readership, scattered across the globe. I am more concerned that my ideas reach people in places like Papua New Guinea, Transylvania, Bourkina Fasso, or Burma than that I gain popularity among my own compatriots. I have friends and acquaintances in all these places, and the mental picture of a reader that hovers in my mind, as I write, includes them. They have bigger problems to deal with than my own countrymen. The subjects I discuss are more urgent for them. I live in the astonishingly lucky country called Canada. Compared to most places in the world, it has no serious political problems to speak of. I will try not to forget that, and I will try not to glibly dismiss the experience of people for whom the definition and application of democracy are life-and-death issues.

0 Comments.