When Walter Scott published the first of his novels, Waverley, in 1814, he was already well-known as a poet. The book was so spectacularly successful that it launched him on a career as a novelist known in every corner of the world. His influence in 19th Century Canada, for instance, was such that nobody with pretention to education was without a set of “Waverley novels”. When I worked on various Ontario farms, I often saw them in Victorian-era farmhouses. I found a complete set in a barn, for which I negotiated payment in hay baling. That set (gorgeously bound) is long gone, but now I have another, acquired in a small Ontario town. Many of the scenes and characters of Scott’s novels are preserved in Toronto street names. Anyone familiar with Canadian history knows that in the 19th Century, its literary icons were, in descending order of importance: the Bible, Robby Burns*, Shakespeare, Scott, and Dickens.

People are now more likely to read one of the later novels, such as Rob Roy, or Ivanhoe, if they read any Scott at all. These are more accomplished, and closer to modern taste. But it’s worth looking at his first effort, because it demonstrates what a revolution in writing Scott initiated. The first five chapters are written more or less in the picaresque style of Fielding (a Scot-hater) or Smollett (a Scot). I suspect that Scott stopped, unsatisfied, and resumed writing after a hiatus, because by the sixth chapter, the reader starts to experience something more like the continuous flow of “you are there” description that you expect in later prose. By chapter 24, we are getting stuff like this:

The various tribes assembled, each at the pibroch of their native clan, and each headed by their patriarchal ruler. Some, who had already begun to retire, were seen winding up the hills, or descending the passes which led to the scene of the action, the sound of their bagpipes dying upon the ear. Others made still a moving picture upon the narrow plain, forming various changful groups, their feathers and loose plaids waving in the morning breeze, and their arms glittering in the sun.

You won’t find anything like that in Fielding. Scott was a great stylistic inovator. You can feel the eighteenth century dropping behind you as you read, and the nineteenth century coming into view. He was also a profound innovator in literary ideas, and in social conscience. Stories about the past, by convention, had always been set in classical antiquity, a kind of symbolic place that was not really meant to be the “past”, as we think of it now, but as a higher plane of reality. With Waverley, Scott invented the historical novel, and to boot he set it in a period whose political conflicts were still fresh and tender wounds in the social fabric of the British Isles. He dared to make the Highlanders of Scotland, heretofore only considered uninteresting savages (even by the Scots in the Lowlands), the central characters of an epic tale. The events of the Jacobite Rising, he revealed to a surprised world, were every bit as worthy of artistic representation as the battle of Thermopylae, or the death of Caesar. This was innovation enough, but he went much further. Scott was, as far as I can tell, the first writer of English prose to describe peasants, servants, and highland outlaws with exactly the same respect and sympathy as the upper classes. Before that, it was barely acknowledged that they were human, let alone that they might have individual characters, interests, and emotions. Scott describes all his characters, of whatever social stratum, with the same objective interest. This now seems to us an obvious desideratum, but when Scott did it, it was revolutionary.

—

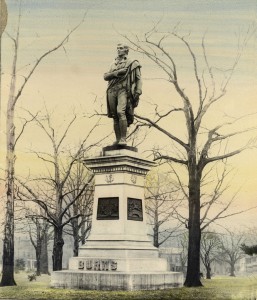

* To illustrate this, I would point to the park two blocks south of where I live. In the late 19th century, it was the centre of the city’s most prestigeous district. Anywhere else in the former British Empire, it would have a statue of Queen Victoria. But in Toronto, it has a huge statue of Burns. The name beneath it reads only “Burns” — no first name being thought necessary.

There are Burns monuments scattered about, with a remarkable variety of representation. The one in Montreal, as big as the one in Toronto, is younger-looking and mannishly sexy. One in Adelaide, Australia makes him really Oscar Wilde-ey, with a baby face and cute pose (I’m not sure what they were thinking). One in Dunedin, New Zealand makes him look like Moses, and one in London makes him look like a chubby businessman.

0 Comments.