My friend, the artist Taral Wayne, recently showed me some ancient Indian coins and asked me what I could tell him about the city-state for which they were minted. He thought I might be interested because he was sure they were from one of the ancient republics. He thought it might be named “Yaudheva”, which was what was scrawled by the coin dealer on its mounting card. There was also another word describing the figure au verso, but neither Taral nor I could make it out clearly.

This was all a bit misleading. Yaudheva would mean something like ” — ? — which is godlike”, an unlikely name for a city. But after looking through my old notes on ancient Indian republics, it dawned on me that it must just be a mix-up between “v” and “y” by the dealer.

Once I knew that it was actually Yaudhiya, then it was simple to untangle. That is the name of one of the republican confederacies of north-western India. I have extensive notes on the Yaudhiya republics. They are not as well-known as the Audumbara republics, but they are reasonably well-recorded from the 5th Century BC onwards. They are mentioned in lots of ancient literature, including the Mahabharata, the Puranas and in Panini’s treatise on grammar. They acquired fame, and a reputation for valour, by defeating Alexander, halting his progress into India. The coin is probably from the Yaudhiyan republic of Rohtika (or Rohitaka), some ruins of which survive in the minor provincial city of Rohtak in the State of Haryana.

The Yaudhiyan confederacy was a collection of city states sharing the same tribal ancestry, much like the early Latin cities. The Yaudhiyan tribes spread across what it now the Punjab. They developed republican forms of government quite early, and maintained them quite late, despite temporary submissions to the Kushan kings. When they threw off the Kushans, they proudly re-established their republican constitutions. But they continued to mint coins following the Kushan model, and corresponding roughly to the Greek drachma, on which the Kushan coin was based.

The inscription on the coin is in Brahmi script, and this is fairly easy to translate, using an online sanskrit dictionary. The kind of easy words that appear on coins didn’t change much in the shift from Sanskrit to the Prakrits. Anyway, the key words are really obvious. The inscription reads “yaudia ganasia jaia”, which means, roughly “hail to the yaudhiyan people!”. This clinches the identification of it as the product of a republic. Such an inscription would never appear on a coin struck for a king, and was, in fact, an explicitly republican formula phrase.

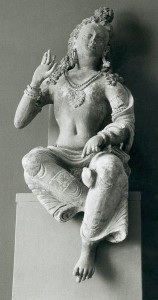

The god on one face has to be Karttikeya, an extremely archaic avatar that probably dates from the Indus civilization, and was eventially absorbed into Vishnu. He appears in the Mahabharata as the son of Agni, riding into the Yaudhiyan territory on the back of a peacock. The peacock motif still appears in folk art around the city of Rohtak, to this day. Karttika was the patron deity of the Yaudhiyan states, making the identification pretty certain. The goddess on the other side is probably his consort Devasan (known as “Kaumari” to the Yaudhiyans). The word that neither Taral nor I could make out was most probably “nandipada”. This word referred to a symbol used by the early Buddhists to designate an elected council, so it was yet another bit of democratic symbolism. This does not mean that it was a Buddhist coin… the terminology was common between Buddhists and the republics from which they drew their political terminology. Karttika is recognized in Buddhism as equivalent to the Hindu god Skanda.

The coin is of northern (Punjab or Haryana) origin, but Taral’s observation that it “looked southern” in style was very astute. The cult of Karttika traveled south and seems to have become popular in the medieval Tamil Chalyuka states, which later became very Shivaist. Obviously the artistic style and some of the symbols became associated with the strong Shiva worship in the south.

Taral enjoys collecting coins. That particular hobby has never attracted me, but I would definitely make an exception for this coin. It’s an article that I would certainly like to have, perhaps mounted on a frame and displayed in my living room, along with my Hausa sword, my Escher print, and my vial full of Sahara sand. It is such an intense concentration of early democratic symbolism! It would fit in well with an ancient greek ostracon (a broken potsherd used for voting), or a traditional Amerindian council pipe.

But it would mean more than that to me. It would be a reminder of a transformation in human society that has been in the works since the first millennium BC, and is only now starting to really gather steam.

Ancient India, in that era, was a patchwork of city states and confederacies like Yaudhiya. Politically, these states underwent convoluted struggles between monarchist, aristocratic, oligarchical, and democratic factions, identical to those recorded in the history of Athens. The world religion of Buddhism emerged during this struggle, and was closely identified with the democratic factions. It was in this hotbed of controversy that many crucially important ideas made their first known appearance.

The ancient world had three major focal points of population, economic activity, and cultural invention: the valleys of the Yellow and Yangtze rivers in China; the plains of northern India encompassing the drainage of the Indus and Ganges; and the more diffuse cluster of activity encompassing the Tigris and Euphrates, the Nile, and the East Mediterranean Sea. Each developed early urban civilizations, writing, and sophisticated technologies. By the first millennium BC, the three foci began to have significant interactions. A maze of trade routes, over land and sea, connected the three areas. Along these routes, additional urban centers and “echo” civilizations popped up, in due course. Thus came into being a continuum of intensified human activity, with an east-west axis, along which trade goods, inventions, artistic motifs, and ideas could travel. Eventually, this axis would extend tentacles eastward as far as Japan; south-eastward into Southeast Asia, Indonesia, and the Pacific; south-westward along the coast of Africa; and north-westward into Western Europe. India, snuggly in the middle, tended to get everything, and in the early phases of this process, was probably the global centre of both economic and intellectual activity. One has only to glance at the work of Panini to see this: his Sanskrit grammar shows an analytic approach, employing the clearly articulated concepts of root, phoneme and morpheme which were only understood by European linguists two thousand years later. In fact, modern structural linguistics developed from the study of Panini, rather than from the usual Greece-Rome-Medieval-Renaissance sequence of influences. His use of metarules, transformations, and recursions hinted at things like the Turing machine and the information theory underlying modern computing. Panini was able to operate on this sophisticated intellectual level because he was not a hick. He was living in the most information-rich and cosmopolitan part of the world.

Similarly, almost all of our mathematics comes from India. The modern numerical system, with its all-important “zero”, seems to have originated in the early Buddhist universities (such as Nalanda) in central India, and rapidly evolved into an advanced mathematics. Indian mathematics disseminated over the web of trade routes, along with the closely associated game of chess and the practice of multiple-entry book-keeping, displacing cruder systems of mathematics. Try doing algebra with Roman numerals! The whole world now does its math with Sanskrit numerals, transmitted through Persia, the Arab world (hence they are called “Arabic Numerals” in English), and ultimately everywhere. When we cash a “check” at a bank, we are using the Persian word for it, as it was formulated by Parsi merchants in the city of Broach, not far from modern Bombay. And we use the same word when we make a winning move in chess, for the same reason.

The important thing about this “world-wide web” of trade routes was that it didn’t matter where something was invented. Eventually, anything created anywhere would find its way to every place on the continuum. Whether it was a manufacturing process, like silk-making, an idea, like algebra, or an artistic style, it would spread like a good joke on the internet.

What I am leading up to, here, is a discussion of what, for want of any better word, I will have to call Cosmopolitanism. Actually, I wish I could coin a more distinct and appropriate term. But let’s use cosmopolitanism for now.

There have always been people who were not content to live out their lives in one valley, or to confine their thoughts to the traditions of one place. No matter what sentimental attachments to their origins they might have, they need the stimulus of the new, the distant, the exotic, to make their lives complete. They need to be able to choose from a big smorgasbord, to make their own particular sandwich. They want more than just the same old baloney.

Perhaps the first place that any large number of people could express this attitude was Afghanistan and Central Asia in the period 300BC to 700AD. During this period, the cities of this region were the Grand Central Station of world civilization. It was here that Buddhism became a world religion, spreading eastward into China and the Far East. It was here that chains of silk road cities converged from five directions. It was here that the classical art of the Greek world fused with Indian and Chinese styles to form what is sometimes called “Greco-Buddhist” art. The earliest versions of this art style have traditional subject matter from India interpreted with sculptural techniques and poses almost identical to those in Greek sculpture. By the end of the period, the various influences were so interwoven that, looking at one Bodhisatva from Seventh Century Afghanistan,

you could hardly guess where it was from. A representation of the Greek hero Hercules acting as protector of the Buddha speaks for itself, and another Bodhisatva (not shown) from nearby Xinjiang, in western China, would look at home in a European church.

The public in these cities had access to everything that could be had in the world. They attended theatres that played the tragedies of Sophocles and Euripides, the comedies of Aristophanes, the dance dramas of Bharata Muni, and the Sanskrit plays of Bhasa and Kalidasa. They wore silks from China and cottons from Egypt. They worshiped, at various (and overlapping) times in Zoroastrian, Mithraist, Hindu and Buddhist temples, Bon and shamanistic sacred sites, Jewish synagogues, Christian churches, and Muslim mosques. Zoroastrianism, perhaps the first of the “universal” religions (that is, meant to be applicable to any people, regardless of locality or ethnicity), originated there. European, Chinese, and Indian travelers frequented these regions. Some of the texts from the region include sophisticated debates between Buddhists and Greek Philosophers. As late as the twentieth century, huge caches of such cosmopolitan texts were found in remote mountain villages.

Even when Islam came to dominate the region, in the middle ages, some of the greatest minds of the Islamic world, such as Ibn-Sina (Avicenna) and Al-Farabi flourished in the Central Asian silk road cities. It was not until the disastrous Mongol invasions that the region began to decline.

It’s not surprising that the Taliban, today’s quintessential enemy of everything that is civilized, tolerant and cosmopolitan, destroyed the colossal Greco-Buddhist statue at Bamyan, a masterpiece of that wonderful syncretism. This was a disgusting act of ignorance, fanaticism and barbarism.

The Islamic world, at its height, created an atmosphere conducive to cosmopolitanism. One of my childhood heroes was Ibn-Battuta. If ever there was a “man of the world”, it was he. Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Battuta (أبو عبد الله محمد ابن بطوطة ) was a native of Tangier, Morocco, of Berber origin (as was St. Augustine, btw). Addicted to travel, he covered roughly 117,000 km (73,000 miles) over a thirty-year period, making copious notes of his observations, which were, on the whole, urbane and humane. Unlike most medieval travelers, he was interested in the texture of daily life.

He crossed North Africa, explored the Nile, toured through the Middle East, then traveled the Silk Road to Central Asia. After living in Mecca for awhile, he began another journey, exploring Ethiopia and much of East Africa. A third voyage took him through the Byzantine Empire. He met the Emperor Andronicus III Palaeologus during his month stay in Constantinople. He went north, to the middle of Russia, across Central Asia again to Afghanistan, then down to India, where he held a position as judge in an Indian sultanate. Eventually, leery of the instability of the regime, he talked the Sultan into appointing him ambassador to China, which he reached after a long and adventurous detour to Indonesia and Vietnam. Eventually, he grew homesick, and re-crossed the entirety of the hemisphere, while the Black Death was sweeping ahead of him. However, he could not resist side trips to Italy and Spain. Barely home long enough to catch his breath, he realized that there was a whole unknown world to the south needing exploration. His journey to West Africa is our first historical source for that region.

Finally, he returned home to Tangier for a quiet, and well-earned retirement. He published his adventures in A Gift to Those Who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Traveling. I am happy to say that there is a crater on the Moon named after him. [6.9° S 50.4° E, in Mare Fecunditatis, if you want to look for it]. He would have loved going to the Moon.

Even among people whom he found rather crude (he was not impressed by the standards of personal hygiene among Europeans, for example), Ibn-Battuta was unusually sympathetic and hopeful for the best. When kidnapped, attacked by pirates, or threatened with execution (which happened now and then), he showed little rancor. Though he always assumed the religious superiority of Islam, he knew the difference between a principle and an arbitrary custom. He was a true cosmopolitan.

Ibn-Battuta was, of course, an exceptional person. When he undertook his travels, the physical difficulties involved were mind-boggling. He usually journeyed alone, at his own expense, and entirely on personal whim, motivated by pure curiosity. We can say this of no other great traveler before recent times.

We are now entering a new century, and a new millennium.

And in this new period, travel anywhere around the world is relatively easy. Many of the totalitarian regimes of the last century have fallen, opening up new areas for relatively unhindered travel. English has become the “Latin” of the world, a convenient second language, used almost everywhere, and it is gradually losing its historical associations with colonialism and cultural arrogance. At the moment, there are several competing “economic engines” producing relatively high standards of living, and generating popular and high culture. Much of the world is well-educated. There are already many families that have come to think of themselves as essentially global citizens. A Gujarati Hindu family that spent four generations in Uganda, then dispersed to London, Amsterdam, Sydney, Los Angeles, Trinidad, Vancouver, Montreal, and Singapore will, by necessity, have a worldliness previously known only to multi-millionaires, royalty and diplomats, though they may be doing nothing more spectacular than owning corner stores, running muffler shops, clerking in banks, or programing computers.

Above all, the internet now allows any child in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan to chat with another in Tuvalu as easily as if they lived next door. Those children are not going to grow up in the same way, or think in the same way, or experience the world in the same way, as any of those who lived in the last ten thousand years. We will soon have thousands of Ibn-Battutas, then millions of them, then hundreds of millions of them. Even the current pull-blankets-over-your-head trend in today’s America, and the retrogressive paroxisms of Islamic and Christian fundamentalism that we are currently experiencing, are probably just the death rattles of expiring mentalities. It is hard to imagine a generation raised to maturity on the internet taking them seriously.

This does not mean that a majority of people will exhibit much cosmopolitan sophistication. Most of us tend to fit in to whatever pattern of tastes and customs surrounds us at first hand, and most of us want to have a home and a family and a neighbourhood that remains fairly stable. Only a few of us are afflicted with chronic wanderlust, or feel a perpetual yearning for novelty and the exotic. But if you walk through a modern city like Toronto, or Amsterdam, neither of which is particularly large or politically powerful, you will not only see a tremendous variety of people and customs, but a level of personal idiosyncrasy, and tolerance for it, that would have been impossible only a generation ago. The park down the street from me, a small neighbourhood gathering place, seems to accommodate a bible study group, gay sunbathers in thongs, a Filipino family barbecue, school children playing ball hockey while chattering in Russian and Tamil, some others playing basketball, mothers minding babies in strollers while reading paperbacks, chess-players, kids smoking marijuana in a circle, a girl dancing, a couple of surly-looking punks, old men passing around a bottle of scotch in a paper bag, a man in a jelebi reading the Qur’an, small children splashing in a wading pool, and a group of drag queens rehearsing a performance of As You Like It, without anyone feeling particularly out of place, and without anyone even thinking they are in anything but a normal situation.

When I was a child, in Northern Canada, I might as well have been living on an uncharted desert island. The world was as remote and unreachable to me as the planets in the science fiction stories I read. For all intents and purposes, New York City, or for that matter, an ordinary suburb, might as well have been Isaac Asimov’s Trantor. The world was something I deduced existed from the vague hints supplied by a handful of library books, and a picture encyclopedia my mother bought in installments.

I have reacted to this, perhaps to the amusement of others, by attempting to absorb as much of the world as I can. I’m determined to treat my whole planet with the nonchallance of a city-dweller dropping into another neighbourhood to check out a new restaurant, to feel “at home” anywhere on Earth. Timbuktu? Kathmandu? Tegucigalpa? Just another “neighbourhood”, with its own style, its own peculiarities and attractions, but just as much where I have a right to be as anyplace else. This is, of course, not really possible. The world is too complex, has too many cities, too many countries, too many wonders, and too many secrets for me to experience them all before I drop dead of exhaustion, just as I will never be able to read all the books I want to, or hear all the music I want to. My cosmopolitan experience will always be superficial.

But then, if I were to enclose myself in one place, follow some rigid and conformist pattern of behaviour, restrict myself to a narrow range of experience, and maintain only a handful of friendships with people of similar background, age, and locality, I would still be just as superficial. Because the infinite subtlety of human individuality would defeat me just as thoroughly. A person is lucky if they think they can understand one human being other than themself.

0 Comments.