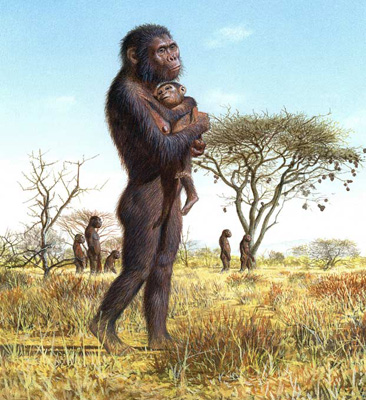

Did early hominins evolve on the savannah? Almost anyone who reads works on paleoanthropology would say “yes.” I would like to explain why I’m tempted to say “no.”

A long time ago, I was chatting with an ornithologist. We were discussing the Canadian province of Saskatchewan, the southern third of which consists of the classic North American prairie landscape. I casually referred to some “prairie birds”, including among them the willett and the killdeer. My friend corrected me. “Those aren’t prairie birds at all,” he said. “They live on the riverbanks. That’s a totally different ecosystem. It doesn’t matter that it’s only a few hundred yards wide and six hundred miles long, it’s not the prairie. Different plants and animals, living a different lifestyle.” This was something I hadn’t grasped. The prairies of Saskatchewan support species like the lark bunting, the bobolink, the western meadowlark, and the sharp-tailed grouse, which all nest, feed and frolic on the grasslands, and are all bona fide “prairie birds”. Further to the north, in the great Canadian forest, you will find woodland species like the blackpoll and Tennessee warbler, the pine siskin, and the nuthatch. But the willett and the killdeer live and work in a riparian niche, the complex ecosystem of riverbanks and lakesides, which is fundamentally different from the grasslands that surround them.

In the 1980’s, when I read extensively on the subject of human evolution, I noticed that paleoanthropologists did not make this distinction. Virtually every book and article discussed some aspect of hominin evolution “on the savannah.” Now, a savannah is a grassland, much like the prairie of Saskatchewan, except that it is dotted with trees that are not sufficiently close together to form a canopy. Like prairie, its ground cover is grass, forming a tighly woven matrix. It supports a variety of grazing animals, and the predators that dine on them. Most of us have a mental picture of the African savannah, formed by numerous television nature specials and old films like Born Free. Almost every book or paper about hominin evolution talks about the savannah as the ecosystem in which it took place. Yet, whenever I read particular reports of hominin fossil finds, it transpired that the actual site involved was, at the time the creature was living, the banks of a river, a lake or a stream. In other words, from the point of view of any field naturalist, not on the savannah.

Why is this distinction important to the study of human evolution? Well, in the books I consumed in the 1980s, the mental image of the savannah as the crucial environmental determinant of hominin evolution was so powerful that it generated no end of dubious speculation. Man the Mighty Hunter still dominated ideas of hominin evolution, and virtually everything about our predecessors’ bodies, as interpreted through fossil remains, invited explanation as an adaptation to hunting on the savannah — despite the occasional sarcastic remark from female paleoanthropologists that, after all, the dentition of hominins and other evidence pointed to the importance of gathered vegetable food. But nobody was busy concocting scenarios in which tuber-digging drove modifications in skeletal structure. Some of the ideas that floated about were downright absurd. Hominins supposedly lost their fur so they could sweat more efficiently as they ran after game on the savannah (despite the fact that no other savannah hunter, such as any of the big cats, found any disadvantage in possessing fur). The notion that language evolved so that hunters could shout instructions at each other, and that upright posture evolved to facilitate running after game still have currency. Even back in the 1980s, I found these interpretations far from plausible. I was pretty familiar with hunters in various environments, and I knew perfectly well that any hunters who ended up doing a significant amount of running were pretty poor, and probably unsuccessful hunters. Successful hunting is done by predicting where game is likely to be, spotting evidence of animal presence, tracking the animals down, and surprising them where they are, usually by maintaining silence and concealment. Most traditional hunters have an elaborate code of hand signals to use when they hunt in groups, because the last thing you want to do is make noise. If the game is on the run, pursuing it in the same fashion is likely to fail. Most large game animals can run faster than humans. Expending a huge amount of calories in running, on the slim chance that you will catch up with prey, is a shortcut to starvation. Human beings have evolved to be pretty good runners, compared to other primates, but they are not in the league of dozens of game species that have remained resolutely quadrupedal. Links between bipedalism and hunting, and between language and hunting struck me as an absurd Daffy Duck cartoon of hominins running across the grasslands, waving spears and shouting. Few seemed to notice that such an evolutionary pathway would perforce lead to greater sexual dimorphism, rather than the steadily decreasing dimorphism in the fossil record. If male hunting tactics drove skeletal change, then there would be nothing driving the same change in females.

So it was that, strictly as a reading observer, and not as any kind of professional in the field, I began to look around for a more plausible scenario. Now, the reader must not get my intentions wrong. In some areas of science, such as ornithology and optical astronomy, there is a strong tradition of “amateur” participation. Ornithology depends on the observations of many thousands of non-professionals, and their contribution to science is respected. But archaelogy and paleoanthropology are fields that attract all sorts of non-professional cranks, and most professionals in these fields shudder when they hear the word “amateur”. I am not a scientist working in any aspect of human evolution. I am merely someone who follows the science as it appears in publication, for my own edification, and because my studies of human society and history include human evolution and prehistory as part of a comprehensive overview. My speculations were then, and are now, merely for my own entertainment.

It struck me, back then, that constantly calling upon the environment of the savannah was a red herring. Remembering the words of my ornithologist friend, I tried to keep in mind that early hominins were riparian critters, inhabitants of river banks and lakeshores. I surmised that they spent far more time near water than out on the grasslands, a pattern that has been replicated by nearly every human society in subsequent history. Now, what are the outstanding features of such an environment? Two come quickly to mind. One is that a riverbank has a complex ecology with a wide variety of food sources for any creature that has the curiosity and dexterity to poke and pry. The other is that it is an extremely dangerous environment. The grazing animals that live on the grasslands must come to lakes and rivers to get water. But they don’t stick around. It is precisely there that they are most vulnerable to predators. In Africa, they rely on the safety of numbers, with herds accepting losses from big cats or crocodiles with each trip to the water source. Early hominins would have faced the same peril, though they would be a less desirable dinner than a tasty gazelle or water buffalo. Being attacked by a predator when going to the river for water is actually still a significant peril for humans in rural Africa. But suppose this danger could be turned into an opportunity?

The opportunity I had in mind was theft. What if you could take advantage of the fact that game animals will come to the riverside or lakeside, and that predators would follow them and kill them? What would be needed would be some way of driving the predators away after they made their kills, then stealing the fresh kills. There had been, even back then, some speculation about early hominins being scavengers rather than hunters, but I think those who were advancing this idea were thinking more of the kind of scavenging that is done by minor carnivores that “clean up” the kills of major predators, who usually leave significant amounts of leftovers after they have gorged themselves on the best bits. This is not what I had in mind. I was thinking, rather, of hominins dividing their attention between gathering the numerous tidbits that can be found on riverbanks — birds’ eggs, crayfish, nuts, tubers, small burrowing animals, fruit, berries, frogs, fish — and the theft of fresh kills from predators. How do you steal from a big cat? You let it make its kill, then you drive it away. But, how do you drive it away?

You throw rocks.

The more I looked at the physiological changes that distinguished early hominins from their simian relatives, the more they seemed to me to line up with throwing rocks. Chimpanzees regularly throw things (usually excrement, which they fling as a sign of hostility), but they are not very good at it. Their wrists are not well-shaped for it, their fingers are too long, and their arms and shoulders don’t have the right configuration for pitching things accurately. But it is precisely these features that are dramatically modified in early hominins, and the changes are as dramatic as those in the lower body and spine that favour bipedalism. Human beings, the inheritors of these changes, may not be able to run like a cheetah, or outperform other animals in many tasks, but they are spectacularly good at throwing things. One has only to look at children playing baseball or cricket to see that humans have evolved phenomenal throwing skills. Early hominins had all these features — they have remained remarkably stable ever since. They probably were as good at throwing rocks and hitting the mark as we are.

This scenario also plays into the riverside/grasslands dichotomy. Walk around on a grassland and try to find a rock that will fit into your hand. You won’t. It’s along river banks that you find pebbles and rocks, and especially rocks that have been rounded by tumbling to make them fit in the hand, and deposited in handy piles. A small group of hominins, able to collect and stockpile throwing rocks, able to throw them accurately, able to work together, sometimes throwing from concealment, sometimes surrounding and attacking from all sides, should have been able to drive away even a top predator like a big cat, leaving a fresh kill for the taking. Hominins would not have had to find animals, because animals would have come to them, to known drinking places. Hominins would not have had to bring down an impala or a buffalo, because a predator would have done it for them. It would have been dangerous work, requiring as much courage as any form of hunting, but it would have been a viable strategy, one that could have provided the intermediate evolutionary feedback that ultimately lead to pursuing large game. Bipedalism, the good binocular vision already extant among primates, and strategic mutations in the structure of the wrist and shoulder, would have constituted a dealing of the cards that would have trumped the big predators. Observing when and where game animals would come to drink would have been in harmony with the constant observation that accompanied all the other forms of food acquisition characteristic of a riparian environment. Unlike the savannah grazers who came to the water hesitantly and departed as quickly as they could, hominins would have been able to stick by the shore and exploit its resources thoroughly.

I reasoned that bipedalism was more useful in this context than in chasing game on grasslands, and that

most of the rather odd changes in skeletal structure that appeared among early hominins fit in better with this scenario. Tool use, which appears quite early in the form of modifying hand-sized rocks and pebbles, also seems to unfold naturally from it. First you throw rocks, then you begin to select rocks that throw best, then you stockpile rocks, then you devise ways of carrying rocks, then you start breaking rocks up to get the size you want, then you start modifying them by striking them against each other, then you start devising new uses for them (scrapers, pounders, cutters, wedges). The need to carry throwing rocks and the need to make food caches, hanging from trees, or buried in river banks, would have stimulated another range of tools: containers. Unfortunately, containers tend to be made from perishable materials that leave no remains, so they have been sorely neglected in studies of early technology. All these processes, including the throwing, would not be gender-dependent. Even if males took the lead in the “theft-hunt” there would still be sufficient reason for females to develop along similar lines, and most of the skills and consequent attributes would overlap with other forms of food gathering. Hunting on the savannah would not have been something that drove evolutionary changes, but a later extension and modification of the original strategy. Even today, the hunting undertaken on the savannah by traditional-style hunters in the Kalahari or the Australian outback has more in common with riparian food-gathering techniques than it does with the hunting done by animal predators. It’s all based on close, calm observation, and coordinated activity, not on the ability to exert energy in sprinting.

Some of these points had been made long before, by the advocates of the “aquatic ape hypothesis” (Max Westenhöfer, Alister Hardy, and Elaine Morgan), but their viewpoint was not taken seriously by the great majority of scientists when I was doing my first reading, and is still not taken seriously today. Nor am I an advocate of it. However, while some of the points overlap, recognizing that our ancestral environment is better described as riparian than savannah-based is not the same as the aquatic ape hypothesis. The stone-throwing scenario did not play any part in the aquatic theory. I have a feeling, however, that focusing on the riparian environment is somewhat taboo, because it suggests an “edging toward” a theory which is usually considered to be cranky.

So, in the 1980s, I settled on this image of hominid evolution, purely for my own way of envisioning human origins. I occasionally discussed it with friends, but little else. Now, here we are, decades later, and I’m in the middle of one of my cyclical reading binges in paleoanthropology. How is my imagined scenario looking now?

Well, I’m happy to say that many lines of inquiry have been moving things in its direction. Most of the trends make me feel that my speculations were anticipitory. There is still a lingering habit of describing our ancestral habitat as the “savannah”, but there’s been a steadily growing realization that the ecological issues are more complex. The environmental background of hominin evolution was not just a static reproduction of the modern African veldt. The “mighty hunter” theme is considerably toned down, and there is more attention given to food gathering (though it is rarely linked to major physiological changes). The skeletal changes have been reconsidered from a greater variety of theoretical viewpoints. There have been significant studies made, in recent years, of the physiology of human and primate throwing skills. One recent researcher even casually mentioned that rock-throwing might have been used to drive away predators. All that’s missing is a small shift in viewpoint, a realization that all these modifications of the older views can be reshaped into a coherent whole.

0 Comments.