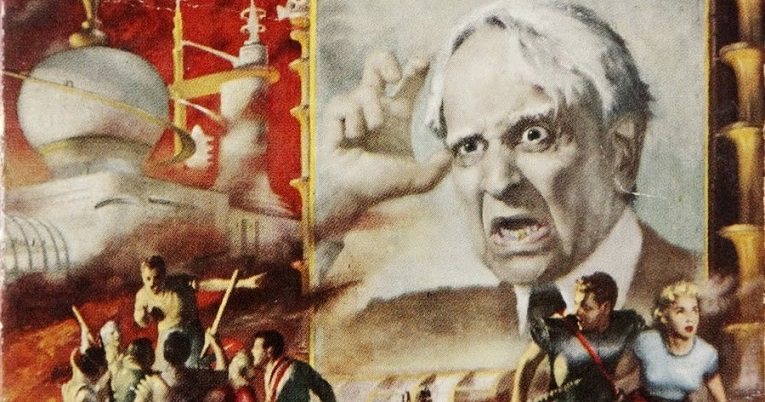

In a hurry to get out the door, I grabbed a paperback at random for subway reading. It was a battered copy of Robert Heinlein’s Revolt in 2100 which I had last read in 1985. It’s three stories are early Heinlein, material that had first appeared in the pulp magazines in the 1930s and 1940s. The stories that he wrote at that time were framed within a putative “future history.” That is to say, that the stories were not directly connected, but all existed in the same projected imaginary future, covering several thousand years. Much was made of this “future history” at the time, but Heinlein abandoned the project to pursue other writing paths from the 1950s until his death in 1988. The books that collected the “future history” stories each reproduced a chart placing the stories in time, with notes on technological, social and political events. It was, Heinlein always maintained, a work of speculative imagination, not of attempted prophecy. But some of its speculations weren’t too far of the mark. In stories written in 1940 an 1949, he had the first landing on the moon take place in 1978. In subsequent reality, it occurred in 1969. But what is especially interesting is that the “future history” has the United States succumb to a fundamentalist religious dictatorship somewhere close to the year 2017. One of the stories is about the rebellion against this dictatorship. At the end of the volume, first published in 1953, Heinlein provided a postscipt, Concerning Stories Never Written, in which he explained that some of the stories listed in the chart, those taking place during the early part of the dictatorship, he chose not to write because the subject matter was too depressing. Concerning their main premise, he wrote:

As for the second notion, the idea that we could lose our freedom by succumbing to a wave of religious hysteria, I am sorry to say that I consider it possible. I hope that it is not probable. But there is a latent deep strain of religious fanaticism in this culture; it is rooted in our history and it has broken out many times in the past. It is with us now; there has been a sharp rise in strongly evangelical sects in this country in recent years, some of which hold beliefs theocratic in the extreme, anti-intellectual, anti-scientific, and anti-libertarian [1].

Further on, he added:

…a combination of a dynamic evangelist, television, enough money, and modern techniques of advertising and propaganda might make Billy Sunday [2]’s efforts look like a corner store compared to Sears Roebuck. Throw in a depression for good measure, promise a material heaven here on earth, add a dash of anti-Semitism, anti-Catholicism, anti-Negroism [3], and a good dose of anti-“furriners” in general and anti-intellectuals here at home and the result might be something quite frightening — particularly when one recalls that our voting system is such that a minority distributed as pluralities in enough states can constitute a working majority in Washington.

Heinlein imagined his fictional dictator, Nehemiah Scudder, as a backwoods hick bankrolled by big-money tycoons and helped along by the Republican establishment, with murky ties to the Ku Klux Klan. The key to his power is his use of television. This is remarkable considering that broadcast television in the United States had existed for only three years when Heinlein wrote this. Few people thought television was politically significant until a decade later. Equally interesting is his reference to the peculiarities of the American electoral system that went largely unnoticed until they made Nehemiah Scu…— I’m sorry, I meant Donald Trump — the President of the United States of America. Religious fanaticism is not the only component of Trumpism, which is a totalitarian ideology similar to Nazism, Communism and Fascism. Like all such totalitarian movements, it brings together many disparate groups and motives. But religious fundamentalists form a considerable block of Trump’s credulous “core” following — and among them many are “Dominionists”, i.e. believers and promoters of a literal religious dictatorship abolishing the separation of Church and State. There is even a bizarre movement that explains Trump’s obvious irreligion, sexual perversion and personal corruption as “proof” that he is a vehicle of divine intervention — a typical sort of mental gymnastic that one expects from the religious fanatic.

Heinlein is a writer who has been bizarrely co-opted by some of the most evil and treasonous movements in today’s America. He is often quoted by people who are essentially disciples of Nehemiah Scudder. A similar process has taken place with George Orwell. Orwell, an anti-totalitarian who utterly despised Conservatism, is regularly quoted by Conservatives to support the very things that Orwell opposed. Everybody who thinks and writes seriously has to take into account that their work might be exploited and distorted in this fashion.

—-

[1] the term “libertarian”, in 1953, did not signify the “Libertarian” political movement of today, but instead meant roughly what the term “liberal” is now used to signify.

[2] Billy Sunday (1862–1935) was an evangelist with fundamentalist views whose popularity peaked somewhat before World War I. He pioneered many of the techniques used by later evangelists in mass rallies, which were then modified for radio and television. He attached himself to the Republican party, and campaigned against immigration from Europe, the teaching of evolution, dancing, card-playing, attending the theatre, reading novels, and the usual sexual “sins”. He was one of the key motivators in the movement toward alcohol prohibition that culminated in the 18th Amendment in 1919.

[3] The use of the terms “Black” and “African-American” were unknown in 1953. Liberals and non-racists at that time referred to African-Americans as “Negro”, as did most African-Americans themselves.

0 Comments.