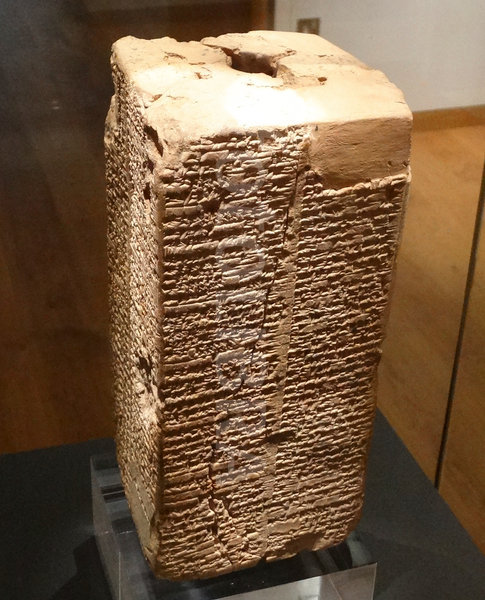

The earliest known historical document is a Sumerian king list, of which there are 16 extant copies. It is somewhat mythical in tone (the second king, Alalgar, is said to have ruled for 64,800 years. But many of the kings seem to have been real, and some seem to have had humble origins, which the chronicle is careful to point out. We are told that “The divine Dumuzi, the shepherd, ruled for 36,000 years”, that “Etana, the shepherd, who ascended to heaven and put all countries in order, became king; he ruled for 1,500 years”, and “The divine Lugal-banda, the shepherd, ruled for 1200 years”. Not only shepherds aspired to kingship: “The divine Dumuzi, the fisherman, whose city was Ku’ara, ruled for 100.” He was the king just before Gilgamesh, of epic fame, who is generally thought to have been a real person. Other tradesmen in the king list include Kiš, Su-suda, the fuller, Mamagal, the boatman, Bazi, the leather worker, and Nanniya, the stonecutter. Altogether, even in a long king list, this seems a remarkable number. Perhaps there is, embedded in this list, a hint at some misinterpretation in our ideas of the nature of Sumerian kingship.

The earliest known historical document is a Sumerian king list, of which there are 16 extant copies. It is somewhat mythical in tone (the second king, Alalgar, is said to have ruled for 64,800 years. But many of the kings seem to have been real, and some seem to have had humble origins, which the chronicle is careful to point out. We are told that “The divine Dumuzi, the shepherd, ruled for 36,000 years”, that “Etana, the shepherd, who ascended to heaven and put all countries in order, became king; he ruled for 1,500 years”, and “The divine Lugal-banda, the shepherd, ruled for 1200 years”. Not only shepherds aspired to kingship: “The divine Dumuzi, the fisherman, whose city was Ku’ara, ruled for 100.” He was the king just before Gilgamesh, of epic fame, who is generally thought to have been a real person. Other tradesmen in the king list include Kiš, Su-suda, the fuller, Mamagal, the boatman, Bazi, the leather worker, and Nanniya, the stonecutter. Altogether, even in a long king list, this seems a remarkable number. Perhaps there is, embedded in this list, a hint at some misinterpretation in our ideas of the nature of Sumerian kingship.

But most remarkable of all was a woman king (apparently not a queen who came to power through widowhood), Kubaba. The text reads: “In Kiš, Ku-Baba, the woman tavern-keeper, who made firm the foundations of Kiš, became king; she ruled for 100 years.” Surely there’s a interesting tale behind this terse entry. If she is a real historical figure (and one shouldn’t assume so), her reign may have been in c.2400 BC. It’s thought that she overthrew the rule of En-Shakansha-Ana of the 2nd Uruk Dynasty to become monarth. The people of the ancient Near East certainly thought her remarkable. Kubaba (or Ku-Baba or Kug-Bau) also appears in the text known as the Weidner Chronicle, in this most remarkable passage:

In the reign of Puzur-Nirah, king of Akšak, the freshwater fishermen of Esagila

were catching fish for the meal of the great lord Marduk;

the officers of the king took away the fish.

The fisherman was fishing when 7 (or 8 ) days had passed […]

in the house of Kubaba, the tavern-keeper […] they brought to Esagila.

At that time BROKEN [An indication by the writer that the tablet he was copying was damaged.] anew for Esagila […]

Kubaba gave bread to the fisherman and gave water, she made him offer the fish to Esagila.

Marduk, the king, the prince of the Apsû [the sweet waters below the earth], favored her and said: “Let it be so!”

He entrusted to Kubaba, the tavern-keeper, sovereignty over the whole world.

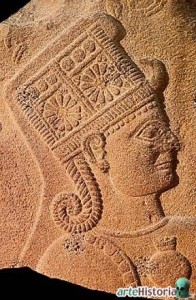

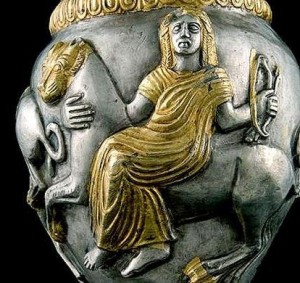

Her rule was associated with peace and prosperity, and shrines to her honour appeared throughout Mesopotamia. She seems to have been slowly transformed into a Mother Goddess popular in the Kingdoms of Mitanni, as the tutelary goddess who protected the Syrian city of Carchemish, and then later in Hittite, Luwian and Phrygian cosmologies. As a goddess, she was often represented holding a mirror in one hand and a poppy capsule or pomegranate in the other. She still retained her name Kubaba among the Luwians, on the edge of the Greek world. To the Phrygians she was “Mother Kubelya”. and from them the Greeks seem to have gotten their goddess Cybele [Κυβέλη]. In most places, she was the subject of orgiastic cults. Cybele’s most ecstatic Greek followers were males who ritually castrated themselves, after which they were given women’s clothing and assumed “female” identities.

Of course, in the intellectual climate of today, pundits would probably be debating: “Is she a success because she’s a woman, or because she’s a tavern-keeper?”.

Representations of Kubaba/Kubelya/Cybele from various times and places:

0 Comments.