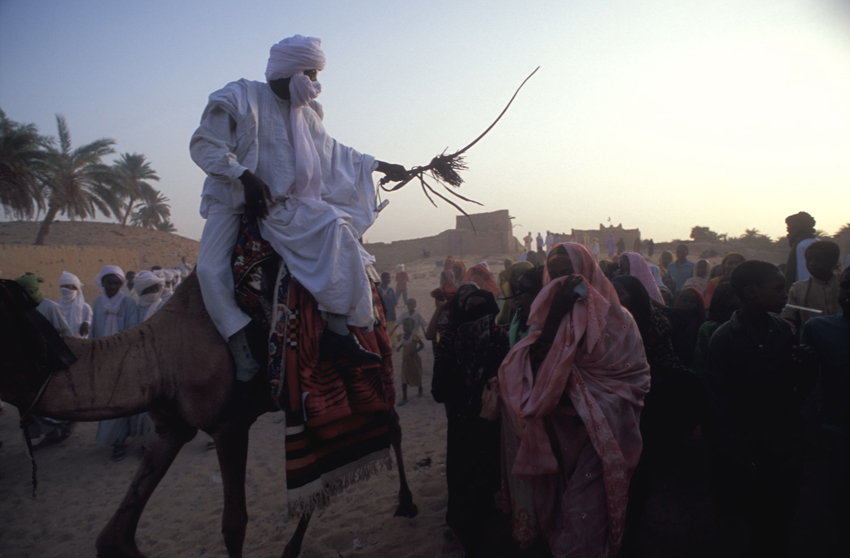

It seems that a relentless treadmill of events forces me to write, in this blog, about nothing but dictators, famines, and wars. For those of you who are tired of it, let me confess that I am, too. I wanted to devote a new entry to one of my real passions ― landscape, music, reading, nature, erotic pleasure, the exquisite freedom of the road. But an article forwarded to me unleashed a flood of memory and opened up private boxes that I’ve generally kept shut. And it was about a dictator. Now, I write a lot about dictators, and the observant among you will notice that I don’t much like them. But, in most cases, this is the result of studying history. Dictators are people I’ve mostly encountered in books. But there is one exception. There is a dictator with whom my relationship is more concrete, and has nothing to do with books. He is one of the “small-fry”. His crimes are monstrous, but his numerous victims were people the world cared nothing about. The slaugther and horror took place right next door to the current slaughter in Darfur, and was on the same scale, but in those pre-internet days it might as well have taken place in another solar system. The man I’m talking about is Hissène Habré.

Category Archives: AS - Blog 2008 - Page 4

Monday, April 14, 2008 — Jeune Afrique 8 avril 2008 AFP: Les députés modifient la Constitution pour juger Hissène Habré — A Personal Ghost Comes Back in a Brief News Report

16106. (David Matas & Hon. David Kilgour) Bloody Harvest: Revised Report into Allegations of Organ Harvesting of Falun Gong Practitioners in China [report]

David Kilgour has been one of Canada’s longest serving Members of Parliament (27 years), as a Cabinet Minister, and as Secretary of State for Asia-Pacific Affairs. Few Members of Parliament are as widely respected. One journalist has written: “in the past 25 years, no Canadian could take this kind of moral time-test and pass with such flying colours as David Kilgour.” — and no Canadian politician comes even close to him as a consistent and principled advocate of human rights. He has published four books on varied subjects, ranging from Espionage to Canadian-American relations. David Matas is a lawyer and lecturer on constitutional law, international law, and civil liberties. He was in the Canadian Delegation to the Stockholm International Forum on the Holocaust, and since 1997 has been the Director of the International Centre for Human Rights & Democratic Development. Read more »

Wednesday, April 9, 2008 — Tibetan Freedom Movement: Beware of Slimy Fellow-travelers

It has been wonderful to see the public protests against the 1936 Berlin Olympics soon to be held in Beijing. For once, an instinctive revulsion against totalitarianism is driving a global movement of protest. But every legitimate protest movement attracts slimy elements, who seek to cash in on a human rights issue to cover up their anti-human-rights agenda. Both the Civil Rights movement and the Anti-War movements in the 1950s and 1960s were infiltrated by totalitarians, seeking to exploit a just cause for their own nefarious purposes. Read more »

Wednesday, April 2, 2008 — Distinguishing Between Fake and Real Human Rights Issues

A friend of mine has been complaining about a much-publicized legal case, where a Sikh employee at a lumber yard is demanding that he be exempted from new safety laws, which require a hard helmet when working with lumber. There is no question of the employer using the law to further prejudice or racism. Sikhs are highly respected in the community. The employee has been there for years, and the company wanted to solve the problem by shifting him to an indoor position, where there would be no conflict. In the distant past, there have been several legal squabbles where it was obvious that regulations were being used to further intolerant agendas. However, there have been none of those kind of things, to my knowledge, for decades, and this certainly is not one. Is this a “human rights” issue, as many claim? No, it is not. Read more »

Saturday, March 29, 2008 — The Poisoning of a People

I just saw an old movie from the early 1980’s called Testament. It was an attempt to show the lives of the people of a small American town after a nuclear war. It’s a very simple film. In it, the nuclear war happens off-stage. It portrays a California town, far from targets. As it gradually loses contact with the rest of the world, its citizens do the best they can to maintain their families and community, while radiation sucks away their lives. The film was made with respect for its audience. The people in it seem to come from another America, one where you would expect that people would do their best, even in the most hopeless conceivable situation. A few exploiters, a few look-out-for-number-one assholes turn up, to be sure, but most people are ready and willing to behave like free and civilized men and women, even when faced with this ultimate test.

I recognized the film’s basic truth, because I knew those people. Decent, hard-working Americans, who generally treated each other with mutual respect. There were millions of them, across the country. The film was set in Northern California, a place I had lived, and knew well. A few years later, there was a devastating earthquake, there. Those same kind of people were everywhere, behaving with both competence and decency. Read more »

Monday, March 24, 2008 — What Alika Lafontaine Tells Us About Ourselves

There is an interesting television contest here in Canada. It’s called Canada’s Next Great Prime Minister. People between the ages of 18 and 25 are asked to submit a five-minute Youtube presentation in which they address one current political issue. Ten finalists are chosen, and brought to a “political boot camp”. From these, four are selected to be voted on by the audience. They not only present their views, but are subjected to an intense grilling from a panel of three former Canadian Prime Ministers and one Provincial Premier (yes, in Canada, Prime Ministers appear on game shows, and even on comedy skit shows). There is a $50,000 prize. Read more »

Saturday, March 15, 2008 — Barking Up the Wrong Tree

Read any history book, and chances are you’ll encounter presumptions, explicit or implicit, about something called “cultural evolution”. Historians have long felt that historical events were taking place within the framework of some kind of process or processes which should be described using terminology borrowed from the biological sciences. Societies, we are told, “evolve” in the same sense that equus “evolved’ from eohippus.

Read any history book, and chances are you’ll encounter presumptions, explicit or implicit, about something called “cultural evolution”. Historians have long felt that historical events were taking place within the framework of some kind of process or processes which should be described using terminology borrowed from the biological sciences. Societies, we are told, “evolve” in the same sense that equus “evolved’ from eohippus.

But societies are not biological organisms, and they are not species. Moreover, the term “society” does not correspond to any real thing with which either organism or species form credible analogies. Organic evolution is not an apt, or relevant analogy to apply to human cultures. Those who seek to describe human history as a parallel to biological evolution are profoundly misunderstanding both.

A species is defined, biologically, as the sum total of individual organisms which are sufficiently close, genetically, to be able to successfully reproduce. While there may be practical difficulties in determining how and where this limiting factor applies in given cases (these are called “species problems” in biology), all cases are ultimately supposed to be determined by the same test, in the same frame of reference. In this sense, “species” is a reasonably objective and consistent concept in biology. When we say that Odobenus rosmarus [Walrus] is a species and that Acer saccharum [Sugar Maple] is a species, we are defining each by the same standards.

The terms “society” and “culture”, however, are not defined by any regular and consistent principle. They do not refer to anything that is agreed upon by historians, and when historians talk about “cultural evolution”, they could be referring to almost any arbitrary conglomeration of individual human beings, reified into a hypothetical identity. They may be applying their hypothetical template to whoever happens to be in some arbitrarily defined geographical area, or to some people who speak the same language, or to people who are subject to a particular set of laws, or to people who are related by putative kinship, or who are mobile but traveling together, or any nebulous assembly of these elements. There is no agreed upon principle defining a society or a culture. The subdivisions of the human race being discussed are not made by any coherent principle, and there is no consistent test or value involved. This alone makes talking about “cultural evolution” nothing more than a vague analogy to biological evolution, and a dubious one, at that. Read more »

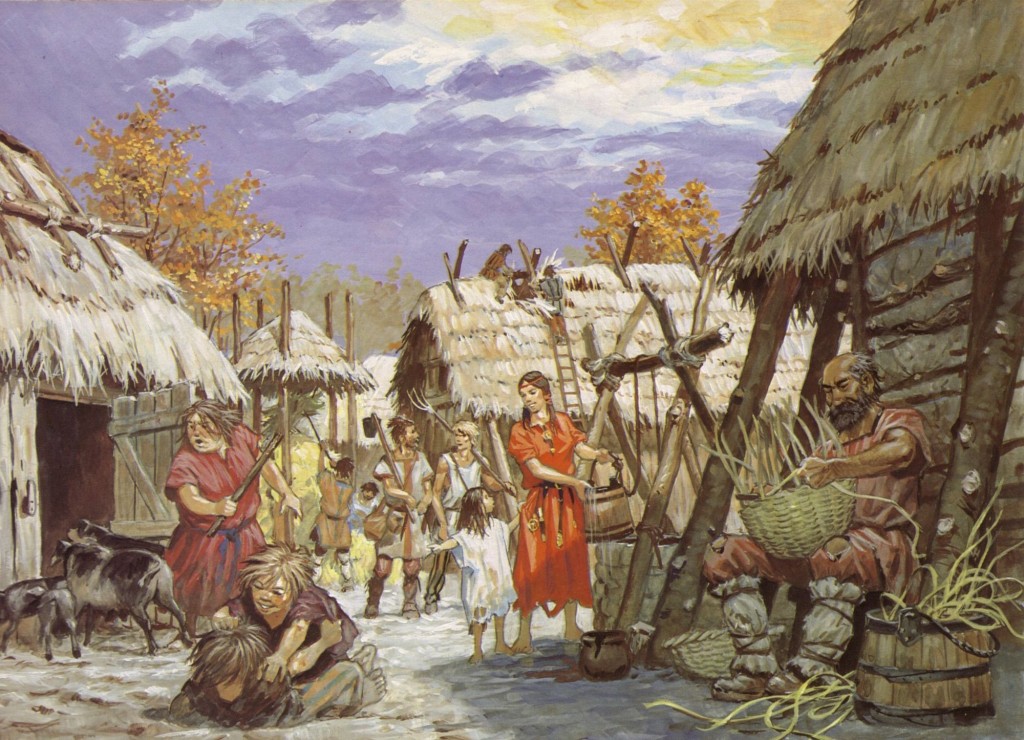

Friday, March 12, 2008 — “I Called the New World to Redress the Balance of the Old”… A Final Word on the European Neolithic

I’ve been asked to explain exactly what I think happened during the period when agriculture was introduced to Europe, and how it differs from the current consensus among prehistorians. First of all, let me make it clear that I’m proposing a modification of that consensus, not a radical alteration of it. I think that the currently most accepted views are hampered by a number of factors: 1) an over-reaction to the previous generation’s reliance on hypothetical migrations, resulting in a preference for static models of human behaviour, 2) a failure to profit from useful comparisons with the history and anthropology of the New World, 3) the pervasive influence of invalid notions of economics and social evolution, inherited and uncritically absorbed from 19th century thinkers.

The dominant school, today, of interpreting the Neolithic arose in reaction to earlier schools of thought, which viewed prehistory as a series of migrations and invasions of ethnic groups, each one held to account for some difference in material culture. Language and ethnicity were, with only perfunctory reservations, assumed to be congruent. The spread of agriculture in Europe and the spread of Indo-European languages were assumed to be different events, taking place at different times. It was assumed that agriculture spread into Europe, from its origins in the Middle East, starting sometime around the sixth millennium BC. Much later, Indo-European tribes of conquerors, empowered by their domestication of the horse, swept across Europe (as well as Iran, Central Asia, and India) imposing their language, religion, and social structure on everyone in their path. The “original homeland” of the Indo-Europeans, these putative conquerors, was thought to be somewhere in the present Ukraine, and much effort was made to determine this location by examining the various Indo-European languages. Thus, the original farmers of Europe were held to be non-Indo-European-speaking natives, subsequently overpowered by an Indo-European élite, who imposed their language on all but a few isolated groups — the Basques, the Finno-Ugrian peoples of the North, and the Etruscans. The most eloquent champion of this model was the Lithuanian-American archaeologist Marija Gimbutas (1901–1994). Gimbutas envisioned a pre-Indo-European agricultural society in Europe which was matristic and “Goddess-centered”, and peaceful, while the conquering Indo-Europeans were patristic and violent. These Indo-Europeans were identified as specifically being the Kurgan culture of the western Eurasian steppes. This rather cartoonish view of the Neolithic, which relied on culturally comfortable notions of gender duality and also on traditional, but biologically naive, ideas of race and ethnicity, had a tremendous influence, not only on historians, but on popular culture. Read more »

SECOND MEDITATION ON DICTATORSHIP (written March 1, 2008)

The argument behind this series of meditations is that aristocratic elites, whether they are dressed up in military uniforms, business suits, or the regalia of royalty, are identical in purpose and function. Differences between them are trivial and cosmetic, not structural. The term “dictatorship” applies equally to all places where an unelected gang of hoodlums rules over people and territory, whatever their supposed ideology or whatever style they chose to prance around in. I further contend that they are neither morally legitimate, nor “government” in the sense that democratically elected administrations are. Dictators are merely criminals, no different from the criminals that rob convenience stores or attack women in darkened car parks. The only difference is the amount of money they steal and the number of people they murder or maim. Read more »