I’ve been asked to explain exactly what I think happened during the period when agriculture was introduced to Europe, and how it differs from the current consensus among prehistorians. First of all, let me make it clear that I’m proposing a modification of that consensus, not a radical alteration of it. I think that the currently most accepted views are hampered by a number of factors: 1) an over-reaction to the previous generation’s reliance on hypothetical migrations, resulting in a preference for static models of human behaviour, 2) a failure to profit from useful comparisons with the history and anthropology of the New World, 3) the pervasive influence of invalid notions of economics and social evolution, inherited and uncritically absorbed from 19th century thinkers.

The dominant school, today, of interpreting the Neolithic arose in reaction to earlier schools of thought, which viewed prehistory as a series of migrations and invasions of ethnic groups, each one held to account for some difference in material culture. Language and ethnicity were, with only perfunctory reservations, assumed to be congruent. The spread of agriculture in Europe and the spread of Indo-European languages were assumed to be different events, taking place at different times. It was assumed that agriculture spread into Europe, from its origins in the Middle East, starting sometime around the sixth millennium BC. Much later, Indo-European tribes of conquerors, empowered by their domestication of the horse, swept across Europe (as well as Iran, Central Asia, and India) imposing their language, religion, and social structure on everyone in their path. The “original homeland” of the Indo-Europeans, these putative conquerors, was thought to be somewhere in the present Ukraine, and much effort was made to determine this location by examining the various Indo-European languages. Thus, the original farmers of Europe were held to be non-Indo-European-speaking natives, subsequently overpowered by an Indo-European élite, who imposed their language on all but a few isolated groups — the Basques, the Finno-Ugrian peoples of the North, and the Etruscans. The most eloquent champion of this model was the Lithuanian-American archaeologist Marija Gimbutas (1901–1994). Gimbutas envisioned a pre-Indo-European agricultural society in Europe which was matristic and “Goddess-centered”, and peaceful, while the conquering Indo-Europeans were patristic and violent. These Indo-Europeans were identified as specifically being the Kurgan culture of the western Eurasian steppes. This rather cartoonish view of the Neolithic, which relied on culturally comfortable notions of gender duality and also on traditional, but biologically naive, ideas of race and ethnicity, had a tremendous influence, not only on historians, but on popular culture.

However, Gimbutas’ concepts always encountered skeptics and critics, and in the 1980’s, their criticisms were synthesized by the British archaeologist Colin Renfrew. Renfrew’s opinions contradict almost every element of Gimbutas’ imagined Neolithic. He believes that the Indo-European languages originated in the Middle East, in central Anatolia, among the people who first domesticated plants and animals. The spread of agriculture and the spread of Indo-European languages were, he believes, effectively congruent. His argument is that farming, even of the most primitive kind, would automatically support an overwhelmingly denser population, and that whatever hunter-gathering societies existed before the arrival of farmers would have been rapidly outnumbered and displaced. Only a handful of “native people”, who were astute enough to adopt agriculture before they were displaced, managed to preserve their non-Indo-European languages, accounting for the survival of the Basques today. Invasions and conquests by a later Kurgan culture across the huge area from Western Europe to Bengal, Renfrew dismisses as a fantasy. From the 1980’s onward, Renfrew and his followers picked apart the inconsistencies and questioned the archaeological and linguistic evidence for Gimbutas’s thesis. They were largely successful in doing so, and currently, a model that basically reflects Renfrew’s views dominates. It is widely held within the broader framework of what is usually called “Processual Archaeology”, In recent years, there has been a lot of archaeological writing which has either described itself or been labeled as “Post-Processual”, but none of it seems to address the questions under consideration here (and it is sometimes difficult to determine exactly what questions it addresses — it seems to consist mostly of vaguely associating archaeological sites or artifacts with paragraphs of inchoate, and sometimes completely meaningless jargon lifted from outmoded and inane French philosophical fashions of the 1970’s, much in the same way that you find faded Motley Crue t–shirts on the backs of Brazilian favella children.)

My problem with this consensus is not with its basic elements, but with the way it has been applied. I think that some unexamined “baggage” has accompanied the development of the new consensus, in much the same way that the old one carried along dubious notions that were not reflected in the evidence.

Since the old consensus pictured extensive migrations of warrior aristocrats sweeping across the Neolithic world, the new consensus reacted by emphasizing static populations. They pictured a “wave-front” of agriculture moving out of Anatolia, overtaking the world of hunter-gatherers bit by bit. Great care was taken to picture as little physical movement of people as possible. Each farming family would simply grow, and its children would clear and farm adjacent land. By a sort of random, brownian motion, the farmed territory would gradually expand. It would not be necessary for anyone to have moved more than a few kilometers from where they were born. The aboriginal population of hunter-gatherers would be gradually displaced, and would have played no significant role in this process. Underlying this vision are several presumptions, all of them as uncritically accepted and as dubious as the presumptions that motivated the Kurgan school. The first is the presumption that ancient populations were essentially static, and that nobody knew or was aware of anything or anyone very far from where they lived. The second is that people rarely traveled any great distances. The third is that there is a neat evolutionary progression of societies from “simple” to “complex”, a presumption that has been locked into historical thinking since the nineteenth century, without any coherent definition of either simplicity or complexity. Hunter-gatherer societies are thought to be inherently “simple”, hence their effects must be insignificant, and their displacement by farming societies an inevitable destiny. The fourth assumption is that trade is an activity which can only be associated with later or more “complex” societies; consequently, any archaeological evidence of long distance commerce must be interpreted in such a way as to deny that it is really trade. If there are objects found in one part of Europe that obviously come from another, distant place, then they must have moved there in a gradual, unconscious, and undirected process. Trade must have not really been trade ─ it must have been a kind of ceremonial “gift exchange”. Since some examples of ceremonial gift exchange can be found in every society (for example, anyone who is nice to the Chinese Communist Party has a good chance of getting a panda), and since there are some ethnological examples of products drifting slowly in gift exchanges from tribe to tribe, in isolated areas like the Amazon and Papua-New Guinea, these are taken as the template. All of these presumptions, taken together, fit into a world view of people behaving as unconscious automatons in an “evolutionary” model of neat stages and static populations.

My criticism is based on the fact that we have, in North America, well-documented and understood examples of people operating in a world in which neolithic-style agriculture, hunting and gathering, and nomadic warriors interacted. We know exactly how trade operated among these people, and exactly how goods traveled from one place to another, and have a good picture of how populations moved. We know these things because, in many cases, we have unbroken cultural traditions, and centuries of eye-witness descriptions, to go along with the archaeological evidence. In many cases, we can actually go and talk to people who have practiced neolithic agriculture, were once mounted warriors, or who still practice a hunter-gathering life-style. And the picture presented by all this evidence is very unlike the picture of European prehistory held by the current consensus.

Now, nobody can prove that the customs and economies of North American Indian societies are similar to those of Neolithic Europeans, but it certainly seems logical that our knowledge of them should inform our choices when we make speculative reconstructions of the latter.

I wrote earlier about the extensive mobility and trade of the traditional culture of the Hudson’s Bay region. Now I would like to take a look at a society which offers obvious parallels to early farming societies in Europe.

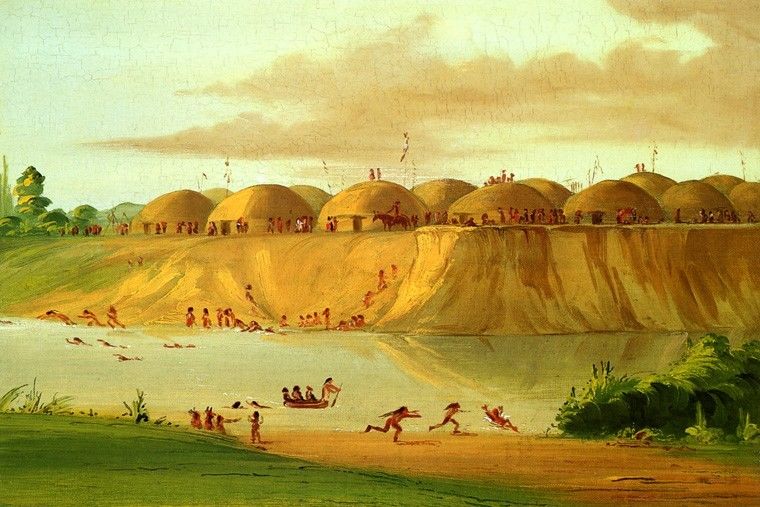

Along the Upper Missouri river, in North and South Dakota, there existed, for roughly a thousand years, a string of agricultural villages. The Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara peoples inhabited the area, which was a fertile river valley crossing the open prairies. The surrounding prairies were inhabited by nomadic, non-agricultural tribes. Archaeological evidence suggests that the Mandans established themselves there sometime before the ninth century AD, and had migrated westwards from previous centers in Iowa and Minnesota, and that they are historically connected with agricultural populations further east. The Mandan were later joined by linguistically related Hidatsa people, and the two groups have influenced each others’ material cultures in such a way as to make it difficult to untangle them, though they remained politically independent from each other. The Mandan have explicit traditions of teaching the Hidatsa how to farm, and the Hidatsa traditions concur with this. Conversely, the Mandan assert that they were taught how to hunt Buffalo after they arrived in the Dakotas. The Arikira were an agricultural people with roots in the southern Mississippi valley, who migrated northward along the Missouri until they encountered the Mandan and Hidatsa. They also came to share many elements of their material culture with the other two, and also remained politically independent. They belong to an unrelated linguistic family.

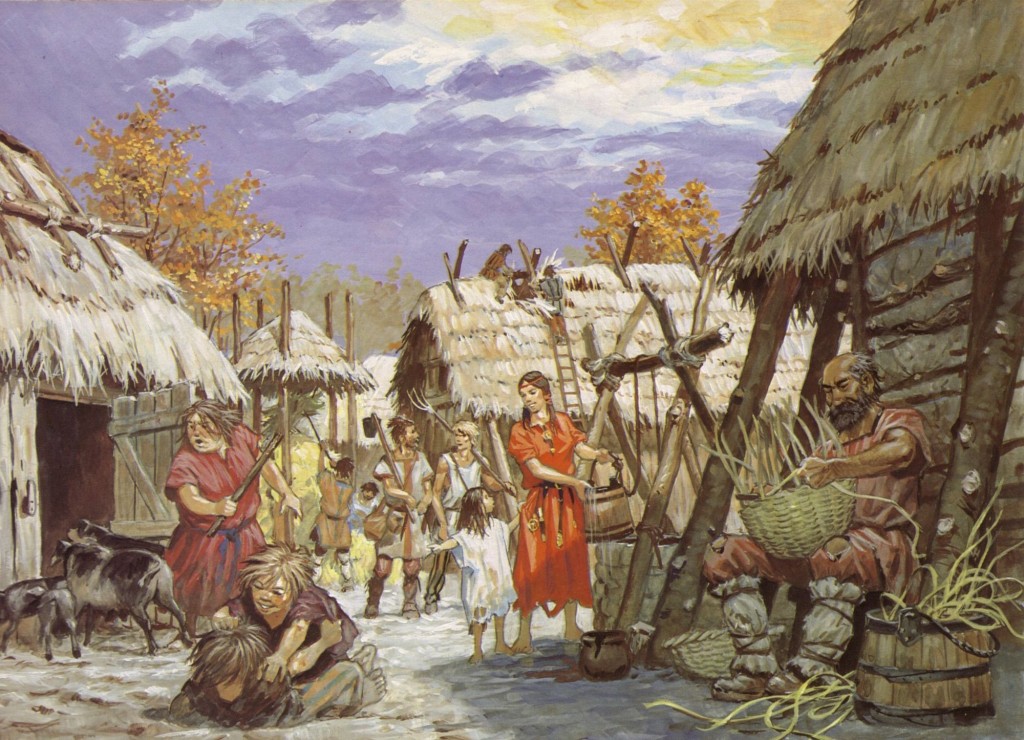

At the height of their prosperity, in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, these three peoples numbered about 25,000 in substantial villages, some better described as towns, with solid, spacious houses, ceremonial buildings and plazas, protected by substantial wooden palisades. Though their farming was intensive, and they produced an agricultural surplus, they hunted buffalo and wild game on the adjacent prairies, and fished for sturgeon and catfish in the river and its branches. They also foraged and hunted for a wide variety of delicacies and raw materials that could be found in the rich river ecosystem. They closely monitored and managed sources of critically essential timber. Agriculture, and the construction of houses and fortifications was traditionally undertaken and managed by women. War and hunting were the principle province of men, though there was some fluidity and overlap in these roles. There were no kings or aristocracy. Each town or village was self-governing, through a variety of councils. Political power was diffused into specialized offices, with no individual or faction exercising power outside of its special function. Some clans claimed preeminence through inherited “sacred bundles”, which conferred authority and prestige in distinct areas, but other, powerful bundles could be purchased, and individuals from low-prestige clans could climb to positions of authority. Warfare, more often than not, was divorced from established privilege, as young men without wealth or influence often stirred up trouble in the hope of gaining influence as warriors. The matrilineal, exogamous Clans, which exercised considerable social control, also cared for the old and destitute. They also made lateral loyalties between villages, and even between tribes, But young men were educated by their fathers’ clans. Age-grade societies cut across clan lines and were entered by purchase. These were repositories of ceremonial traditions, arts, and technical skills. The best description of Upper Missouri village political organization would be a diffuse, multi-layered conciliar politics heavily influenced by an unstable oligarchy. Above the village level, political alliances sometimes followed ethno-linguistic lines, and sometimes did not. The prevalence of warfare serious enough to merit expensive fortification did not, ipso facto, imply that any warrior aristocracy was in charge, as archaeologists often presume in an Old World setting.

We have detailed descriptions of the first contact with Europeans from the journals of the Canadian explorer La Vérendrye and his party. Since La Vérendrye was primarily interested in trade, we have a good picture of the economics of the region from long before any substantial interactions with Europeans. For the next century, only a trickle of similar visitors arrived, and the only notable European influence was the incorporation of some European products into their already extensive system of trade.

This system of trade is what is important to look at closely. It long predates any European influence, is entirely autochtonous in origin, and was not a manifestation of ceremonial gift exchanges or of accidental, unplanned, or unconscious practices. Farmland was owned by village women in individual plots. The average plot produced a substantial surplus, and each woman, after feeding her family, processed the crops, chiefly corn and a variety of squashes, into store-able dried forms, and kept them in individually owned storage caches. The products of fishing, hunting, and gathering were similarly processed to make both fresh, and store-able preserved jerkies, pemmicans, and candies. The food surplus from all these activities was substantial, and there was also a wide range of craft production, including excellent pottery, copper-ware, basketry, fine leathers, farm tools, toys, musical instruments, domestic appliances, and decorative objects. This, too, was undertaken on a scale that considerably exceeded local needs.

This is because the Three Associated Tribes were the region’s preeminent merchant-traders. It is perfectly clear that this trade was not a mere ceremonial “gift exchange” network, nor was it based on prestige items or trinkets. Whatever luxury or prestige goods were exchanged, they were mere side-effects of a large-scale trade in mundane goods, starting with agricultural staples. According to numerous first-hand accounts, “vast quantities” of food products were traded. Both food and non-food products were often manufactured from raw materials purchased from other tribes, then resold to third parties. For example, western hunting tribes sold hides for dried corn and squash, and the villagers turned them into high-quality leather goods to sell to tribes in the East. Sales took place at regularly scheduled trade fairs, organized by the villages, at which individuals sold their stocks. Visitors came from hundreds of kilometers away to buy and sell at these fairs.

The villages of the Upper Missouri were at the heart of a complex network of organized commerce that encompassed two concentric areas. The first area was one of direct trade. This was the zone were buyers and sellers traveled to engage in single exchanges. This zone was approximately the size of England. A larger zone surrounded this, in which trade goods moved by two or three “jumps” until they reached the Three Associated Tribes. This area was the size of Western Europe. There is no evidence that any substantial amount of trade goods traveled in a crawling, incremental fashion from one village or group to another over short distances. This is illustrated by the enduring mercantile connection between the Upper Missouri, and the lower Columbia River. The Crow people were closely related to the Hidatsa. They had accompanied them in their migration from Minnesota, but had not, according to tradition, adopted farming. Instead, they ranged the plains to the southwest, and maintained a special relationship with the Hidatsa, carrying goods back and forth to the renowned Shoshone Rendezvous, seven hundred kilometers to the southwest, near present-day Green River, Wyoming. There, they met Nez Percé, Ute, and Flathead traders, who carried goods to The Dalles, in Oregon, another six hundred kilometers to the west (1,600 km by river). As the Upper Missouri villages were the great entrepot of the High Plains, The Dalles performed the same function in the Northwest, and on a greater scale. Initially, its attraction was as the most productive salmon fishery of the whole Columbia basin. Thousands gathered there, in the fishing season, not just to fish, but to trade. As Elizabeth Vibert describes it, in Traders’ Tales:

Centuries before Europeans arrived in the region, The Dalles had become the nucleus of the Northwest Coast-plateau trade system. It has been argued that in terms of the variety of goods traded there, the diversity of cultures represented, and the sheer intensity and volume of trade, the place was preeminent among Native American trade rendezvous in North America. From the Great Plains came buffalo robes and other buffalo products, feather headdresses, parfleches, and catlinite (pipestone); from the coast, whale and seal bone and oils and ornamental shells, including the prized haiqua (dentalium); from the Great Basin, obsidian and other stone tools; from the Plateau, basketwork, canoes, hemp, and other plant materials, pelts and hides; and from the Plateau, Great Basin, and California, food plants like bitteroot, camas, and wapatoo. Goods traded at The Dalles have been traced to archaeological sites from Alaska to California, and a thousand miles to the east.

To illustrate how things worked, consider the elegant awl cases, which most Hidatsa women carried on their belts to protect a mundane, but essential tool. The Hidatsa crafted beautiful ones, for themselves, and for sale to others. These were decorated with dentalium shell, from the Pacific coast. We can trace the steps the dentalium took to reach the Upper Missouri: from the Tillamook regional trading center at the mouth of the Columbia to The Dalles; from there to a secondary trading center at Snake River or Camas, in Idaho; from there to the Shoshone Rendezvous; from there to the Hidatsa. The product, dentalium, was not by any stretch of the imagination a non-functional prestige artifact. It was a good quality raw material employed to make a high-quality, but utilitarian object used exclusively by women. It was used in many other crafts, by many people west of the Mississippi. The transactions necessary involved only four steps, averaging about 700km in distance. An equivalent trade network in ancient Europe would have stretched from the Black Sea to Britain.

Ceremonial gift exchanges performed the same role they do in modern societies ─ they acted as social lubricants facilitating more practical and extensive commercial transactions, or they marked political negotiations. Chiefs giving out ceremonial gifts had to buy them from producers or traders, in the first place, just as a modern politician giving gifts to a visiting politician has to buy them from the normal economy. Gift exchanges were dependent on the commercial economy, so they could not be the economy. Normal commerce was not managed by kings or war-leaders. There were no kings. Trade was planned and directed by individual entrepreneurs (often women) and by committees and councils convened for the task. Until the advent of the horse, war-leaders, no matter how eminent, did not direct trade. They bought its products, like everyone else. However, the arrival of horses brought to prominence a commodity that could be augmented as easily by raiding and theft as by breeding and trading, and were from the beginning owned by the hunters who doubled as warriors. This produced an important change in who engaged in trade, and how it was done.

It’s perfectly clear that the Three Affiliated Tribes had a good knowledge of large-scale geography, knew where products came from even when they came through intermediaries, and undertook both economic and political strategies to place themselves advantageously in a continent-wide system of trade. La Vérendrye sought out the villages after hearing descriptions of them from hunting peoples in Canada. At the western end of Lake Superior a Cree named Auchagah spontaneously sketched a map for him, on birch bark, that covered hundreds of kilometers. It was no different in conception, technique, or assumptions of significance than with any map that a European would have spontaneously sketched under similar circumstances. The Mandans and other plains peoples made elegant maps drawn on cured buffalo hide that showed river systems in accurate detail, of which we have surviving examples. The Mandan councils immediately undertook negotiations to establish a direct trade with the Canadians and employed a subtle subterfuge to prevent Blackfoot traders from gaining a foothold as middlemen.

When I look at this kind of large-scale trade network, what strikes me most dramatically is that sedentary agricultural people, prairie nomads, fishermen, and isolated bands of hunters all participated in the trade network on an equal basis, and trade was of economic importance to all of them. People could not, in fact, be automatically pegged to a specific category, and there is no evidence that particular modes of production constituted a fixed evolutionary sequence, or distinct “levels”. People who lived as mobile hunters in Michigan also operated large-scale copper mines that supplied customers as far away as Mexico. Other “nomadic” people set up large permanent fish weirs in order to sell the products to distant farming villages, though thy could easily have lived comfortably off of hunting in their area. This did not in any way alter their self-identification with linguistic and cultural relations who did not do this. All these intricate variations lead me to conclude that the trade-networks long predate agriculture, and that agricultural villages expanded into areas, like the Upper Missouri, already well-known through trade and travel. The sites of Mandan villages were selected, I believe, because they were already known to be productive centers of fishing, harvesting wild prairie turnips, berry picking, and good places to drive herds of buffalo over bluffs. North America’s network of rivers was an effective system of highways that could carry goods and people swiftly over long distances, and this network was as familiar to everyone as English people are now familiar with the M4 and M6. Significant gaps between agricultural regions along the Missouri, as well as clear traditions of migration (the three Tribes each arrived from different directions) demonstrate that a slow-moving “wave-front” of agriculture was not how agriculture spread, at least in this part of the world. All the evidence points to agriculture being a practice that took advantage of an already extensive trade and transport network to establish itself at strategic nodes, which were already significant for fishing, specialized hunting, as pre-agricultural trading places, or for the availability of specialty products. The Three Tribes were as much concerned with the availability of suitable construction timber as they were with the fertility of the soil, when they placed or moved their villages, and it is not accidental that a major move created a new village called Like-a-Fishhook.

The scale, complexity, and economic importance of long-distance trade networks has long been familiar stuff among New World archaeologists, but somehow, this has had only reluctant, and devalued influence on the theoretical framework of European prehistory. There, old habits that regard commerce as ignoble, travel as unnatural, pre-ordained stages as the essence of history, and hierarchy as the preferred ordering principle of society still shape attitudes toward the past. Such ideas, of course, influence New World archaeologists and historians as well, but apparently not quite so rigidly.

So, what do these examples from North America, where we have some secure knowledge of social systems and economies, have to say to us when we contemplate Neolithic Europe, where we have none? They can tell us nothing for certain, but they can give us a good idea of what was possible, and even what was most likely.

What seems most likely to me is that agriculture spread through Europe by plugging itself into an already-existing network of trade and travel. It would have involved individuals and small tribes, or clans, moving significant distances, usually along rivers, but occasionally jumping from one river system to another. Agricultural villages would have appeared at locations already economically significant as fishing & gathering settlements, or strategic trading places. Agriculture would not have expanded as a self-contained subsistence strategy, but as part of a widespread “market system”, producing goods for exchange in a pattern that already existed for fish and game products, and for commodities such as furs, amber, and flint, and manufactured goods such as axes and knives. It would not have advanced in a “wave-front”, by the process of slowly adding farms to tbe edges of a uniform block of agrarian culture, as envisioned by Renfrew, but by intensifying nodal points in a web-like network that predated the technology. Rivers, not land, would have been the critical factor, and fishermen and fishing settlements along these rivers would have played a significant role. Notice that, in the North American parallel I contemplate, the largest trading emporium, The Dalles, was first and foremost a fishing center, from which trade radiated via a network of rivers. In this region, sophisticated trade networks clearly preceded agriculture, because it was still not agricultural at the time of European contact. Further north, along the British Columbia coast, villages existed with elaborately ranked aristocracies, commoners, and slaves, but without agriculture, contradicting neat schemes of cultural evolution. Plateau peoples, just as productive and industrious, were even more egalitarian than the people of the plains. Their domestic and commercial management of fisheries, more than 350 species of plants, and dozens of kinds of hunting, in a social framework where most people were multi-lingual, loyal to multiple groups and localities, and put together co-operative enterprises involving hundreds of people at a time, can hardly be called “simple” with a straight face. Their economy was as complex as any farming society’s. Most notions of “simplicity” and “complexity”, and of “cultural evolution” are dubious in the extreme, reflecting unconscious prejudices and a lack of curiosity about how people do things if they aren’t familiar to one’s own experience.

What seems most likely to me is that agriculture spread through Europe by plugging itself into an already-existing network of trade and travel. It would have involved individuals and small tribes, or clans, moving significant distances, usually along rivers, but occasionally jumping from one river system to another. Agricultural villages would have appeared at locations already economically significant as fishing & gathering settlements, or strategic trading places. Agriculture would not have expanded as a self-contained subsistence strategy, but as part of a widespread “market system”, producing goods for exchange in a pattern that already existed for fish and game products, and for commodities such as furs, amber, and flint, and manufactured goods such as axes and knives. It would not have advanced in a “wave-front”, by the process of slowly adding farms to tbe edges of a uniform block of agrarian culture, as envisioned by Renfrew, but by intensifying nodal points in a web-like network that predated the technology. Rivers, not land, would have been the critical factor, and fishermen and fishing settlements along these rivers would have played a significant role. Notice that, in the North American parallel I contemplate, the largest trading emporium, The Dalles, was first and foremost a fishing center, from which trade radiated via a network of rivers. In this region, sophisticated trade networks clearly preceded agriculture, because it was still not agricultural at the time of European contact. Further north, along the British Columbia coast, villages existed with elaborately ranked aristocracies, commoners, and slaves, but without agriculture, contradicting neat schemes of cultural evolution. Plateau peoples, just as productive and industrious, were even more egalitarian than the people of the plains. Their domestic and commercial management of fisheries, more than 350 species of plants, and dozens of kinds of hunting, in a social framework where most people were multi-lingual, loyal to multiple groups and localities, and put together co-operative enterprises involving hundreds of people at a time, can hardly be called “simple” with a straight face. Their economy was as complex as any farming society’s. Most notions of “simplicity” and “complexity”, and of “cultural evolution” are dubious in the extreme, reflecting unconscious prejudices and a lack of curiosity about how people do things if they aren’t familiar to one’s own experience.

I also suspect that the pre-eminence of Indo-European dialects as trading languages may have played as much a role in their spread as agriculture, and would account for the relatively modest degree of divergence they display. If Indo-European speaking farmers had been as immobile as current theory suggests, then after five thousand years of presence in Europe, there should have been considerably more divergence than there is. By 1000 BC, the speech of peasant communities should have been mutually unintelligible every fifty kilometers from each other, the kind of situation you have in New Guinea. But if Indo-European dialects had become lingua-franca along well-frequented trade routes, then their actual degree of divergence makes sense.

Within this framework, it is much easier to understand the complex pre-agricultural settlements like the one recently studied at Argus Bank, in Denmark, where inshore fishing with weirs, deep-sea fishing in boats, river fishing, and hunting supported a substantial population. Early farmers would have been attracted to such places, because they provided a solvent market for surplus agricultural products, and a wide range of useful non-agricultural products to buy with that surplus, just as the Mandan and Hidatsa grew corn and squash where it could be traded for the products of the prairie. It is this kind of dynamic synergy that would create an expansion of population and village life, not self-contained subsistence farming. It is already understood that nomadic pastoralism evolved in symbiosis with settled agriculture, and could not have existed without an agricultural base. I think that we will see that agriculture developed and expanded in symbiosis with fishing and hunting, in a similar way.

Within this framework, it is much easier to understand the complex pre-agricultural settlements like the one recently studied at Argus Bank, in Denmark, where inshore fishing with weirs, deep-sea fishing in boats, river fishing, and hunting supported a substantial population. Early farmers would have been attracted to such places, because they provided a solvent market for surplus agricultural products, and a wide range of useful non-agricultural products to buy with that surplus, just as the Mandan and Hidatsa grew corn and squash where it could be traded for the products of the prairie. It is this kind of dynamic synergy that would create an expansion of population and village life, not self-contained subsistence farming. It is already understood that nomadic pastoralism evolved in symbiosis with settled agriculture, and could not have existed without an agricultural base. I think that we will see that agriculture developed and expanded in symbiosis with fishing and hunting, in a similar way.

This also makes for a much more sensible interpretation of the pattern of goods from distant sources found everywhere in European archaeological sites, and of the mines and production centers that we know produced far more commodities than could possibly have spread by short-distance gift exchanges, no matter how pervasive. You do not dig up hundreds of tons of native copper so that it can trickle away from you in gift exchanges over the next few centuries; you do it because there is a large paying market for copper. Any prehistoric mine that depended on gradual diffusion of its products through its immediate neighbouring people could not long function. It would saturate the local market, then cease to exist. The existence of these mines implies the existence of regular, long distance trade, along rivers, with constant pressure to reduce the number of middlemen.

Anyway, that’s how I picture things happening in Neolithic Europe. It is not a contradiction of the basics of current theory, but it seems to me to eliminate some elements of it that have not been thought through judiciously. I will lay bets that, ten years from now, it will be the consensus, not because I have had any influence, but because further archeology will make it obvious.

Another element of New World history is worth calling attention to, when discussing European prehistory:

One of the most dramatic changes in Native North American society was the introduction of the horse. I find it fascinating to read discussions of how many centuries or thousands of years it must have taken to domesticate the horse, and to spread it’s use in the old world. Some of the speculations and conclusions seem very odd to me.

The horse first appeared north of the Rio Grande when Spanish soldiers subdued some of the Pueblo Indian villages in what is now New Mexico. By the 1650’s, the Spanish were maintaining large herds near Santa Fe and Taos. While the Spanish forbade local Indians from owning or riding horses, some Ute and Comanche prisoners, enslaved by the Spanish, learned how to ride them. When the Pueblo peoples temporarily drove out the Spanish, in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, they had little interest in the animals, but the Ute and Comanche prisoners happily stole them and began to raise them. Within twenty years, they had developed special breeds capable of running alongside buffalo without fear. By 1700, they were selling surplus horses to the Shoshone, the Kiowa and other neighbouring tribes. By 1740, they were making regular roundups and sales trips to the Mandan-Hidatsa trade fairs. By 1770 horses were part of an intricate network of breeding and marketing as far north as Alberta and almost everywhere west of the Mississippi that had terrain that could support them. By the end of the 18th century, there were numerous plains tribes who were so strongly identified with horses and horsemanship that almost every aspect of their lifestyle and material culture reflected it. Among Plains peoples, horses were always individually owned, though they were often borrowed, or rented.

Yet these facts seem to have had little influence on interpreting the evidence for the domestication of the horse in the Old World, or in how it is thought to have been used, or how it is thought to have spread. The impression is given that the ancient peoples of the Old World, unlike those of the New World, were pretty dumb. They domesticated the horse, and just sort of let it hang around for centuries before making it pull a wagon, then spent another thousand years before thinking of riding it, and so on. Perhaps the archaeological evidence supports this. I don’t know. I’m not qualified to judge. But if it does, isn’t it just a little bit embarrassing?

0 Comments.