This was Timothy Findley’s fourth novel, and it attempts to get into the morbid world of the celebrities and intellectuals who cosied up to the Nazis and the Italian Fascists. This was identical, psychologically, to the coterie of celebrities who cosied up to the Communists. It was a loathsome time, in which there were very few voices who spoke for anything good. Everyone was some kind of sleazy creep. Ezra Pound, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, Harry Oakes, Rudolf Hess, and von Ribbentrop appear as characters, among others, all seen through the eyes of a fictional Hugh Selwyn Mauberley (the persona of some of Pound’s poems), whose frozen corpse is found in an Alpine hotel, with a testament scrawled in pencil on the walls of three rooms. It’s a good and intriguing read, but the absence of any character that one can feel any sympathy for left me feeling worn out by the end. But that has always been my response to the intellectual world between the two World Wars. Frankly, I don’t care about the fact that people like Ezra Pound of Bertolt Brecht were talented writers — they were disgusting little pieces of shit, and no amount of cleverness or artistry makes them admirable. The Nazi-Communist-Fascist mentality was the lowest ebb of the human mind, when geniuses degraded themselves into moronic savages. There is probably no way to write about it, or read about it, without feeling ill. We are still suffering the aftereffects of that intellectual holocaust.

Category Archives: BN - Reading 2008 - Page 6

READING – MARCH 2008

15738. (Unto Salo) Ukko, The God of Thunder of the Ancient Finns and His Indo-European

. . . . . Family

15739. (Émile Benveniste) Les valeurs économiques dans le vocabulaire indo-européen

. . . . . [article]

15740. (Bernard Wailes) The Origins of Settled Farming in Temperate Europe [article]

15741. (Bernice Morgan) Cloud of Bone

15742. (Edgar Polomé) Germanic and Regional Indo-European [article]

15743. (William F. Wyatt, Jr.) The Indo-Europeanization of Greece [article]

Read more »

15956. (Timothy Burke) [blog Easily Distracted] Competency as a Cultural Value [article]

This is an interesting discussion of the psychological reality of American politics, and why Democrats from a professional background don’t connect with it. However, it makes unwarranted assumptions about the rationality and “procedural savvy” of the social group the author sees himself as belonging to. In my experience, they have demonstrated exactly the same degree of susceptibility to superstition, magical thinking, and irrational mumbo-jumbo as any of the proles that he contrasts them to. You rarely see this kind of discussion in Canada. We really do live in different worlds, now. It is a good article, making some good observations, despite the patronizing tone, and the annoying use of the silly neologism “competency” in place of the English word “competence”. Available at Burke’s blog Easily Distracted, or through Brad DeLong’s site..

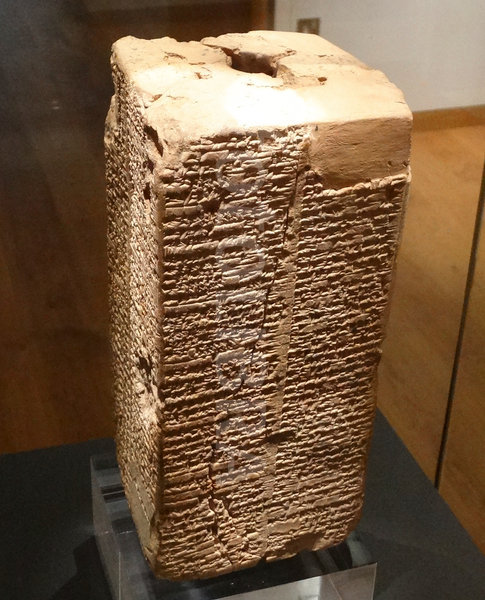

15821. (Anon. attr. to Damiq-ilišu of Isin, ruled 1816–1794 BC) Weidner Chronicle, ABC 19 [aka Esagila Chronicle] 15822. (Anon. late third millennium BCE, Ur III period) Sumerian King List based on version G, an octagonal prism from Larsa

The earliest known historical document is a Sumerian king list, of which there are 16 extant copies. It is somewhat mythical in tone (the second king, Alalgar, is said to have ruled for 64,800 years. But many of the kings seem to have been real, and some seem to have had humble origins, which the chronicle is careful to point out. We are told that “The divine Dumuzi, the shepherd, ruled for 36,000 years”, that “Etana, the shepherd, who ascended to heaven and put all countries in order, became king; he ruled for 1,500 years”, and “The divine Lugal-banda, the shepherd, ruled for 1200 years”. Not only shepherds aspired to kingship: “The divine Dumuzi, the fisherman, whose city was Ku’ara, ruled for 100.” He was the king just before Gilgamesh, of epic fame, who is generally thought to have been a real person. Other tradesmen in the king list include Kiš, Su-suda, the fuller, Mamagal, the boatman, Bazi, the leather worker, and Nanniya, the stonecutter. Altogether, even in a long king list, this seems a remarkable number. Perhaps there is, embedded in this list, a hint at some misinterpretation in our ideas of the nature of Sumerian kingship.

The earliest known historical document is a Sumerian king list, of which there are 16 extant copies. It is somewhat mythical in tone (the second king, Alalgar, is said to have ruled for 64,800 years. But many of the kings seem to have been real, and some seem to have had humble origins, which the chronicle is careful to point out. We are told that “The divine Dumuzi, the shepherd, ruled for 36,000 years”, that “Etana, the shepherd, who ascended to heaven and put all countries in order, became king; he ruled for 1,500 years”, and “The divine Lugal-banda, the shepherd, ruled for 1200 years”. Not only shepherds aspired to kingship: “The divine Dumuzi, the fisherman, whose city was Ku’ara, ruled for 100.” He was the king just before Gilgamesh, of epic fame, who is generally thought to have been a real person. Other tradesmen in the king list include Kiš, Su-suda, the fuller, Mamagal, the boatman, Bazi, the leather worker, and Nanniya, the stonecutter. Altogether, even in a long king list, this seems a remarkable number. Perhaps there is, embedded in this list, a hint at some misinterpretation in our ideas of the nature of Sumerian kingship.

But most remarkable of all was a woman king (apparently not a queen who came to power through widowhood), Kubaba. The text reads: “In Kiš, Ku-Baba, the woman tavern-keeper, who made firm the foundations of Kiš, became king; she ruled for 100 years.” Surely there’s a interesting tale behind this terse entry. If she is a real historical figure (and one shouldn’t assume so), her reign may have been in c.2400 BC. It’s thought that she overthrew the rule of En-Shakansha-Ana of the 2nd Uruk Dynasty to become monarth. The people of the ancient Near East certainly thought her remarkable. Kubaba (or Ku-Baba or Kug-Bau) also appears in the text known as the Weidner Chronicle, in this most remarkable passage: Read more »

15802. (James Turner) Rex Libris: I, Librarian [comix]

I can’t describe this amusing graphic novel any better than the back cover blurb: “The astonishing story of the incomperable Rex Libris, Head Librarian at Middleton Public Library. From ancient Egypt, where his beloved Hypatia was murdered, to the farthest reaches of the galaxy in search of overdue books, Rex upholds his vow to fight the forces of ignorance and darkness. Wearing his super thick bottle glasses and armed with an arsenal of high technology weapons, he strikes fear into the recalcitrant borrowers, and can take on virtually any foe from zombies to renegade literary characters.

15800. (Aron Ralston) Between a Rock and a Hard Place

How could I pass up a book about a guy who is climbing in a part of the Utah Desert that I’m very fond of, gets pinned by a fallen boulder for six days, and has to hack off his own arm with a utility knife to get out of it? Aron Ralston’s book about his experience is actually very well written, and entertaining throughout. He wisely structures it so that his autobiography, chiefly outdoor adventures in the mountains and deserts of the U.S., alternates with the details of his most dramatic experience. It took place in the Canyonlands area made famous in Edward Abbey’s Desert Solitaire. Those of us who are emotionally attached to the red rock deserts of the Four Corners region are generally willing to undergo some hardships to enjoy its beauty — but not quite as much as Aron did.

15772. (Elizabeth Vibert) Traders’ Tales: Narratives of Cultural Encounters in the Columbia Plateau, 1807–1846

I have some problems with this book (mostly impatience with anything anyone says that has the term “post-” in it; that always puts my teeth to grinding). But most of it is reasonable and useful. Of special interest to me:

The basic distinctions that traders [North West Company and Hudson’s Bay Company traders living among the Columbia Plateau Indians– P.P] drew between “fishing” and “hunting” peoples illustrates well the power of contemporary discourse concerning the influence of environment on society. As is made clear in the chapters that follow, the identities these labels describe are in large part inventions of the traders. All Plateau peoples included a range of subsistence strategies — fishing, gathering, and hunting — in their seasonal round… The emphasis itself was seasonally and historically variable, however, and communities described as “hunters” at other times gathered and fished.… … As for the influence of environment on “hunters’ and “fisherme,” the groups that occupied the banks of the Columbia River were cast as hopelessly indolent, supposedly because the river “afford(s) an abundant provision at little trouble for a great part of the year.” Those who lived in areas that were richer in animal life, and particularly those who hunted on the buffalo plains, were judged far more industrious. Clearly, the traders’ material interests figure prominently in the imagery that casts fishing peoples as lazy and hunters as hard-working.

My impression is that many historians, archaeologists, and even anthropologists have hardly progressed at all from the world-view of these Company factors.

15758. (Ceron-Cerrasco, Ruby) ‘”Of fish and men” = “De iasg agus dhaoine”: A Study of the Utilization of Marine Resources as Recovered from Selected Hebridean Archaeological Sites

My whining about the lack of serious attention to fishing in archaeology and theoretical prehistory may be outdated. This report on a recent dig in the Outer Hebrides describes everything I’ve wanted to see done for the last fifteen years. A few dozen projects like this will supply us with the data to transform our understanding of prehistoric economies.

15755. (Flannery O’Connor) Wise Blood

This is a masterpiece of American literature that will present difficulties for a Canadian reader. This was Flannery O’Connor’s first novel, written in 1949. O’Connor (1925–1964) was a native of central Georgia, and the old segregated American South that she writes about more than confirms the adage that “the past is a foreign country.” The world of Wise Blood is closer to another planet than a mere foreign country. Widely regarded as the heir to William Faulkner, literary convention has placed O’Connor in the annoyingly patronizing academic compartments of “Southern Gothic” and “Regional Fiction”. (If you write in New York, of course, that isn’t “regional”). Much is made of the “grotesque” elements in her fiction. But she was not much pleased with that kind of peg-boarding. “Anything that comes out of the South is going to be called grotesque by the northern reader, unless it is grotesque, in which case it is going to be called realistic,” she once remarked.

This is a masterpiece of American literature that will present difficulties for a Canadian reader. This was Flannery O’Connor’s first novel, written in 1949. O’Connor (1925–1964) was a native of central Georgia, and the old segregated American South that she writes about more than confirms the adage that “the past is a foreign country.” The world of Wise Blood is closer to another planet than a mere foreign country. Widely regarded as the heir to William Faulkner, literary convention has placed O’Connor in the annoyingly patronizing academic compartments of “Southern Gothic” and “Regional Fiction”. (If you write in New York, of course, that isn’t “regional”). Much is made of the “grotesque” elements in her fiction. But she was not much pleased with that kind of peg-boarding. “Anything that comes out of the South is going to be called grotesque by the northern reader, unless it is grotesque, in which case it is going to be called realistic,” she once remarked.

O’Connor was a Catholic, something which is pretty normal here in Canada, where it doesn’t involve much in the way of metaphysical or psychological complexity. But in Georgia, it makes one an outsider, and philosopher. O’Connor was fascinated by faith, apostasy, sin and redemption, and in the religiously supercharged world of the South, and especially the region where the Mountain culture interacts with the Deep South, there was plenty of material to chew on. Wise Blood tells the tale of Hazel Mote, traumatized son of a preacher who hates religious faith, but finds himself involved in every kind of religious experience. He is a virtual catalog of heresies and bizarre religious practices, while he tries to avoid belief. He is surrounded by an assortment of odd characters, each one driven by some equally peculiar belief. One character ends up worshiping a mummy in a museum. It all does seem grotesque, a kind of surrealistic fantasy. But the irony is that nothing happens in the book, and no character is represented, that has not existed in real life.

That is the real power of the book. Everything in it is relentlessly faithful to reality. It’s written with incredible control, precision and economy (it is really a novella, rather than a novel). Not a word is wasted, not a word is wrong, not a word is out of place. Dialect and idiolect are rendered with absolute perfection. Sometimes a single, short sentence will create a crystal clear visual image in the reader’s head. The prose sings,

I could not come from a more different cultural background, and my interests and preoccupations could not be more different than O’Connor’s, but this book still held me in complete absorption. What must it do for someone for whom it’s closer to the bone? I would love to sit down and talk over this book with my old friend William Breiding, who must surely have read it. William? Send me your thoughts on this one.

15752. [2] (Roy W. Meyer) The Village Indians of the Upper Missouri: The Mandans, Hidatsas and Arikaras

Current interests led me a second reading of this excellent history (it’s approach is historical, not ethnological) of the Mandans, Hidatsa and Arikaras of North and South Dakota.

Scholars trying to reconstruct the Neolithic societies of Europe, especially regarding trade, early agricultural settlement, and the movement of people, would profit by studying the valley of the Missouri River. Here we have a mixture of first-person eye-witness sources and archaeological data that shows us much about the interaction of nomadic and agricultural peoples, which Old-World historians could learn a lot from, if they bothered to look. The relevance to understanding the European Neolithic seems to me obvious, but the parallels and examples have not been explored or exploited. Exactly why this is, so, I’m not sure. But of particular relevance is the detailed knowledge we have of Mandan and Hidatsa trade: the products involved, how they moved, how far, how many people where involved, and with what economic concepts and processes. They do not at all resemble the picture conjured up by historians in the Old World of How Things Must Have Been Done. One cannot prove, of course, that the European Neolithic farmers, hunter-gatherers, and nomads had the same kind of economy as existed in the center of North America in a later period, but the data certainly is relevant to guessing what was likely or probable. Read more »