14673. (Anthony Boucher) The Case of the Seven Sneezes

14674. (Marshall McLuhan) The Gutenburg Galaxy

14675. (Gerald Posner) Secrets of the Kingdom ― The Inside Story of the Saudi‑U.S. Connection

14676. (Evangeline Walton) The Children of Llyr

14677. (Nancy Phelan & Michael Volin) Sex and Yoga

14678. (Jared Diamond) Guns, Germs and Steel

Read more »

Category Archives: BP - Reading 2006 - Page 4

READING – JUNE 2006

14694. (Shoma A. Chatterji) Subject: Cinema, Object: Woman, a Study of the Portrayal of Women in Indian Cinema

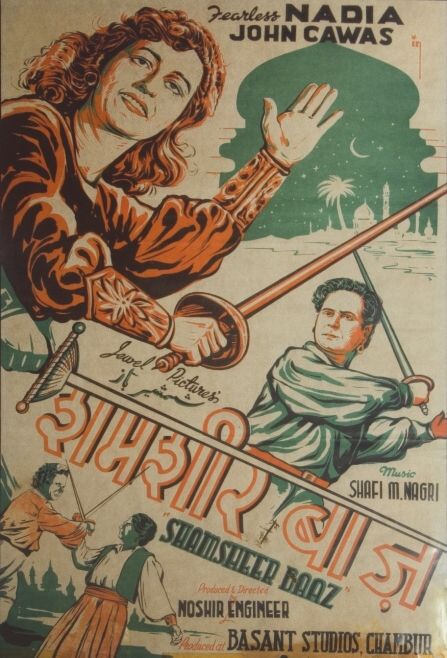

Who would have guessed that, as early as the 1930’s, there was an action heroine in Indian cinema, who did all her own stunts, and defied all the conventions of passive and simpering femininity, and played second fiddle to no male? That’s the most remarkable information in this study. Starting with Hunterwali (1935), Fearless Nadia starred in a series of extremely popular adventure films. “The female protagonist entered the scene on horseback, with the clarion call of ‘Hey-y-y‑y’, hand raised defiantly inn the air, riding in with the pride and arrogance that was more befitting of Douglas Fairbanks.” This remarkable actress had started out as a steno-typist, but, inclined to be plump, took dancing lessons. Then she joined a traveling circus, and a ballet troop. Her amazing film stunts (all real) included hoisting strong men on her back, fighting four lions, swinging from chandeliers, leaping from cliffs into waterfalls. She rode, swam, tumbled, wrestled and fenced her way through numerous films, often with a mask and a whip, until she was nearly fifty.

Who would have guessed that, as early as the 1930’s, there was an action heroine in Indian cinema, who did all her own stunts, and defied all the conventions of passive and simpering femininity, and played second fiddle to no male? That’s the most remarkable information in this study. Starting with Hunterwali (1935), Fearless Nadia starred in a series of extremely popular adventure films. “The female protagonist entered the scene on horseback, with the clarion call of ‘Hey-y-y‑y’, hand raised defiantly inn the air, riding in with the pride and arrogance that was more befitting of Douglas Fairbanks.” This remarkable actress had started out as a steno-typist, but, inclined to be plump, took dancing lessons. Then she joined a traveling circus, and a ballet troop. Her amazing film stunts (all real) included hoisting strong men on her back, fighting four lions, swinging from chandeliers, leaping from cliffs into waterfalls. She rode, swam, tumbled, wrestled and fenced her way through numerous films, often with a mask and a whip, until she was nearly fifty.

14693. (Walter Mosley) 47

I’ve been remarking that some of the best written books, in recent times, have been published in the “juvenile” market. This book proves my point. It’s a beautifully written, emotionally powerful, and highly imaginative demonstration of what it means to be a slave. No topic is closer to my heart, and, frankly, I wish that I had written this book. “47” is a plantation slave, who, in the 1830’s, encounters an alien being who is stranded on earth. He tells his tale from the viewpoint of now, since he has become effectively immortal, and still retains the 14-year-old body. But the science fiction element of the story is underplayed. Mosley concentrates on making the reader hear, taste, smell, and feel the reality of slavery. It’s a fine piece of work.

(J. R. R. Tolkien) Tree and Leaf

The first item, the essay “On Fairy Stories”, is essential reading for anyone with a serious interest in Tolkien. It makes clear exactly what he was doing, and why. It was written during the height of the dominant position of “realism” in literature, when anything even remotely imaginative was considered trash by literary people. Tolkien was particularly annoyed by those who saw fantasy, especially the particular kind of fantasy that he called “fairy-story”, as exclusively for children. He writes:

Among those who still have enough wisdom not to think fairy stories pernicious, the common opinion seems to be that there is a natural connexion between the minds of children and fairy-stories, of the same order as the connexion between children’s bodies and milk. I think this is an error; at best an error of false sentiment, and one that is therefore most often made by those who, for whatever private reasons (such as childlessness), tend to think of children as a special kind of creature, almost a different race, rather than as normal, if immature, members of a particular family, and of the human family at large. Actually, the association of children and fairy-stories is an accident of our domestic history. Fairy stories have in the modern world been relegated to the ‘nursery’, as shabby or old-fashioned furniture is relegated to the play-room, primarily because adults do not want it, and do not mind if it is misused.

Touché. I can still remember when that attitude was gospel, when a good science fiction writer like Kurt Vonnegut had to vociferously deny that he wrote SF so he could be taken seriously, and the encyclopedias described H. G. Wells as the author of Tono Bungay, Mr. Brittling Sees It Through, and, embarrassingly, “some scientific romances”.

contents:

14691. [2] (J. R. R. Tolkien) On Fairy Stories

14692. [3] (J. R. R. Tolkien) Leaf by Niggle

14682. (Tim Wynne-Jones) The Knot

I’ve enthused before about the work of Tim Wynne-Jones. This is an early novel of his. His writing was not quite as sharp as it has since become, but this novel still held my attention. In part, it’s because the story (a sort of fusion of Charles Dickens and Raymond Chandler) focuses on my own neigbourhood in Toronto, and concerns the underside of that neighbourhood at the very time when I was myself part of that underside. I recognize and remember almost every physical feature in the book. Some of the places, buildings, and social configurations no longer exist, but reading this novel brought them back to me with the intensity of the smell of piss in a dark city alley.

READING – MAY 2006

14657. (Dan O’ Neill) The Firecracker Boys

14658. [2] (William Shakespeare) Henry V [play]

(Groff Conklin –ed.) 5 Unearthly Visions:

. . . . 14659. (Eric Frank Russell) Legwork [story]

. . . . 14660. (Walter M. Miller, Jr.) Conditionally Human [story]

. . . . 14661. (Raymond Z. Gallun) Stamped Caution [story]

. . . . 14662. (Damon Knight) Dio [story]

. . . . 14663. (Clifford D. Simak) Shadow World [story]

14664. (Michel Tremblay) Quarante-quatre minutes, quarantes-quatre secondes

Read more »

14671. (Barbara Haworth-Attard) Theories of Relativity

This is a juvenile novel about a teenager living on the streets of an unidentified Canadian city. He is not, strictly speaking, a “runaway”, but the equally common “thrown away”, effectively kicked out of a disfunctional single-family home. Unlike most books of this sort, Haworth-Attard’s treatment is neither sentimental, nor preachy. This kind of street life is something I know well, and I can vouch for the accuracy of most of the details. I found only a few small improbabilities, and those subject to interpretation. The author has done her homework. As a story, it reads well. The characters are believable, and the use of Einstein as a leitmotif is deftly handled. In recent years, fiction aimed at teenage readers is being written at a very high level quality, especially in Canada. Ironically, one has to go to teenage fiction to find the honesty, serious subject matter, and emotional intensity that are vanishing from genre fiction aimed at adults.

14668. (Martin Brauen) Dreamworld Tibet

Of all places in the world, Tibet has attracted the most fantastic mystification. Martin Brauen’s book is a study of the bizarre images, dreams, and supernatural fantasies that people have projected on this land. He explores the various themes, starting with Renaissance speculation about a hidden Christian kingdom in the Himalayas, and proceeding through the fantasies of Madame Blavatsky and her Theosophists; the fictional Shangri-la of James Hilton’s Lost Horizon (and the wonderful Frank Capra film made from it); the racist pseudo-science of the Nazis, who were fascinated with Tibet; the absurdities in the immensely popular books by “Lobsang Rampa”; to modern advertizing that exploits the image of the Dalai Lama, and current movies that still insist on seeing only the religious and “spiritual” side of Tibetan life.

The author is not actually angry about all this nonsense, but he is painfully aware that few people are interested in the reality of Tibet, or the people of Tibet. Read more »

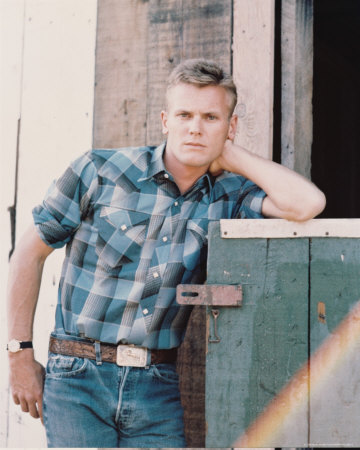

14667. (Tab Hunter & Eddie Muller) Tab Hunter Confidential

I was surprised at how much I learned about how Hollywood works from this biography of a star of the 1950’s. Tab Hunter was a “heart-throb”, an actor who was marketed for his handsomeness. I frankly don’t find his kind of looks very attractive, but many people do. His autobiography is “co-authored”, probably meaning that Hunter was extensively interviewed, provided tape recorded reminiscences, and the “co-author” put it together in first-person voice. It’s a perfectly valid way for an actor, who doesn’t happen to be an experienced writer, to tell his story. In this case, the result seems to be unusually honest. Hunter stumbled into movie acting, and was initially successful because of his looks. He was gay, and went through the complexities, strategies, and perils that gay actors had to face in the 1950s. What it particularly charming about the narrative is the fact that Hunter (real name Arthur Andrew Kelm), who had an impoverished childhood in a rather disfunctional single-parent family, was in person a rather bashful, reticent, and psychologically conservative person, more comfortable with horses than people. His wholesome, boy-next-door image was not an act. However, he was able to attract people like Anthony Perkins and Rudolf Nureyev as lovers. He moved easily in sophisticated circles in the theatre, and in Europe’s high society, without altering his persona. His acting career has never been taken seriously, though he did some fine work on the stage and in television, and clearly cared deeply about his craft. He struggled to get roles that didn’t consist mostly of posing shirtless. But in the end, he was done in by cultural shifts that put his image out of fashion. His most intelligent career move was to appear in John Waters’ 1980 low budget cult film, Polyester. That, and publicly coming out of the closet, won him the respect he had never gotten as a teen idol. The book is not vindictive, but it gives a very believable account of some of the nastier things that went on in the film industry in the 1950’s and 1960’s.

I was surprised at how much I learned about how Hollywood works from this biography of a star of the 1950’s. Tab Hunter was a “heart-throb”, an actor who was marketed for his handsomeness. I frankly don’t find his kind of looks very attractive, but many people do. His autobiography is “co-authored”, probably meaning that Hunter was extensively interviewed, provided tape recorded reminiscences, and the “co-author” put it together in first-person voice. It’s a perfectly valid way for an actor, who doesn’t happen to be an experienced writer, to tell his story. In this case, the result seems to be unusually honest. Hunter stumbled into movie acting, and was initially successful because of his looks. He was gay, and went through the complexities, strategies, and perils that gay actors had to face in the 1950s. What it particularly charming about the narrative is the fact that Hunter (real name Arthur Andrew Kelm), who had an impoverished childhood in a rather disfunctional single-parent family, was in person a rather bashful, reticent, and psychologically conservative person, more comfortable with horses than people. His wholesome, boy-next-door image was not an act. However, he was able to attract people like Anthony Perkins and Rudolf Nureyev as lovers. He moved easily in sophisticated circles in the theatre, and in Europe’s high society, without altering his persona. His acting career has never been taken seriously, though he did some fine work on the stage and in television, and clearly cared deeply about his craft. He struggled to get roles that didn’t consist mostly of posing shirtless. But in the end, he was done in by cultural shifts that put his image out of fashion. His most intelligent career move was to appear in John Waters’ 1980 low budget cult film, Polyester. That, and publicly coming out of the closet, won him the respect he had never gotten as a teen idol. The book is not vindictive, but it gives a very believable account of some of the nastier things that went on in the film industry in the 1950’s and 1960’s.

14554. (Michel Tremblay) Quarante-quatre minutes, quarante-quatre secondes

Michel Tremblay is a giant in Canadian literature, but anglophone readers are generally only familiar with his plays. Les Belles-Soeurs (“The Sisters-in-Law”) transformed french-language theatre in Canada. He was definitely a vanguard, writing vividly in a colloquial Canadian, and exploring new subject matter. Over the years, Tremblay built up a huge corpus of work, including many novels and television dramas in addition to the plays, a “comédie humaine” from the sinews of Montreal. Tremblay is an oddity, an openly gay author who is best known for his understanding of women. Satisfyingly complex roles for female actors are hard to find on the stage, and Tremblay has earned their gratitude and respect.

Michel Tremblay is a giant in Canadian literature, but anglophone readers are generally only familiar with his plays. Les Belles-Soeurs (“The Sisters-in-Law”) transformed french-language theatre in Canada. He was definitely a vanguard, writing vividly in a colloquial Canadian, and exploring new subject matter. Over the years, Tremblay built up a huge corpus of work, including many novels and television dramas in addition to the plays, a “comédie humaine” from the sinews of Montreal. Tremblay is an oddity, an openly gay author who is best known for his understanding of women. Satisfyingly complex roles for female actors are hard to find on the stage, and Tremblay has earned their gratitude and respect.

This is the first of his novels that I’ve read. The main character is a singer whose career stalled after a single album. The book focuses on the period in the early 1960s when Montreal’s music scene was especially vital. Félix Leclerc, Gilles Vigneault, Monique Leyrac, Clémence Desrochers, Claude Léveillée and others were creating fabulous songs, many of them with extraordinarily beautiful lyrics*. Tremblay interweaves history and fiction delicately. The prose style is very, very Canadian, anchored in real speech and real thought, without any affectations. The people are completely believable. The story is structured as an album: ten songs, ten situations, ten meditations on what might have been. It explores something hardly touched on by writers, the soul searching of a life that is neither tragic nor triumphant, but caught, like most of us are, somewhere in between. Read more »