Debussy’s La Mer is so familiar that it’s easy to forget how revolutionary a piece it was when it was finished in 1905. After a gazillion performances, it still remains fresh. We are accustomed to think of it as a pure example of “expressionism”, a kind of musical equivalent of Monet’s fuzzy lily pads and flowers, and it is indeed that. But at the same time, it exhibits a strict classicism in its structure, and romantic dynamism in that a “story” unfolds as each section develops from hints in previous sections, and it travels through the emotions as much as any high romantic symphony. In fact, it is fair enough to call it a symphony, if you think more in terms of the last Sibelius symphony than of Beethoven or Schubert. So it gives us the best of three worlds. Like most people who listen to classical music, I sometimes neglect to listen properly to “concert chestnuts” like this. In fact, it had been quite some time since I had given La Mer any thought. What triggered a return to it was listening to another impressionist work about the sea, much less well-known, Arnold Bax’s The Garden of Fand.

Fand leaves her lover Cu Chulainn (Manannan MacLir in the middle casts a spell of oblivion upon his wife, Fand) — Illustration by Yvonne Gilbert

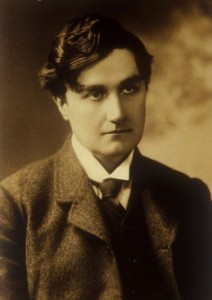

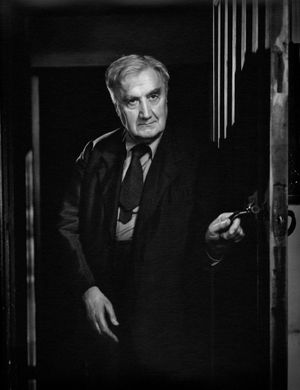

Arnold Bax (1870–1953) was an English composer who became obsessed with Irish music, poetry and mythology. He is best known for a series of tone poems on celtic themes, of which Tintagel (1917) is the best known, and The Garden of Fand (1913–16) is the best. I’ve loved this piece for most of my life, though for a long time could only find a single recording of it. Fortunately, it was by Adrian Boult, the most sympathetic and able Bax interpreter. Bax had little fame or success during his lifetime. The early tone poems had a modest success, but his seven symphonies dropped into oblivion. However, Sibelius felt his work was first-rate, and the two men formed a lasting friendship. It was the advocacy of Adrian Boult that slowly brought Bax back into view, though most of his works were not available on record until the 1980s. Sibelius’s influence is visible in his work, but not obviously so. Debussy’s influence is more obvious, with the Frenchman’s parallel thirds shifting by whole tones, and sparkling woodwind ornaments. But Debussy tends to evoke nature with dispassion, while Bax invokes a more supernatural, even creepy sensibility. The Garden of Fand is based on an ancient Irish epic from the Ulster Cycle tale, Serglige Con Culainn (The Sickbed of Cúchulainn). Fand is a Celtic sea goddess, associated with the transition to the other world, faerie. The perennial Irish hero, Cúchulainn, tangles with her, to his peril. What has always appealed to me about the piece is it’s sinuous, shape-shifting melody, which has stuck in my mind far more than most. Around it, Bax weaves no end of dramatic surprises. It’s a fabulously inventive piece, with sudden changes of tempo and surprising effects. Little twinkling figures transform into sinister fortissimos. Like Celtic myth, the piece is deceptive, nothing ever remaining the same for long, and nothing being quite what if first appears to be… in short, it’s like the sea.