Circumstances have prevented me from attending many live concerts, recently, so I jumped at the chance when Isaac White and his parents kindly invited me to a concert at Grace Church On-the-hill, a handsome Anglican church built in 1912. I arrived early, so I spent an hour wandering around Forest Hill, in Suydam Park, Relmar Gardens, and the Cedarvale ravine before meeting Isaac at the Second Cup. Forest Hill is like a small town embeded in the city, with its own little “main street” and a thick canopy of maples. In the crisp autumn air, the village seems like a Ray Bradbury story re-written by Margaret Atwood. Among the stacks of pumpkins and the drifting red and gold fallen leaves, the Anglican, United Church and Jewish versions of Toronto Respectability compete. No place could seem farther from the woes of the world. The local book store has a strangely morbid display of highly literary titles in its window, with each title accompanied by a card explaining how the author died (did you know that Roland Barthes was run over by a laundry truck?). There are very comfortable public benches on the sidewalks, a rarity in the rest of penny-pinching Toronto. In the ravine, I saw a dog chasing a cat chasing a squirrel chasing a leaf. Read more »

Category Archives: CN - Listening 2008 - Page 3

Elgar, Mozart and Tchaikovsky at Grace Church On-the-hill

The Mannheim School

The palace of the Elector of the Palatinate at Mannheim, where its resident orchestra was the heart of the “Mannheim School”.

Haydn and Mozart did not transform baroque music in a vacuum. Change was in the air, and a number of minor composers contributed to it. Among them were the men clustered in the court of the Elector Carl Philipp, at Mannheim. The best musicians from across northern Europe were drawn there in the mid 1700’s. Composers of the Mannheim school introduced a number of novel ideas into orchestral music, such as a more independent role for wind instruments, adding the newly invented clarinet, and much more variable dynamics (the orchestral crescendo is a Mannheim invention). Haydn picked up on these techniques. As a matter of fact, his famous “Paris” symphonies were commissioned for the Mannheim orchestra. I’m listening to a representative selection of Mannheim orchestral music by the Camerata Bern, under the direction of Thomas Füri: Die Mannheimer Schule, a 1980 box set from Archiv. It includes Franz Xaver Richter’s Sinfonia in B‑flat, and his Concerto for Flute and Orchestra in E minor; Johann Stamitz’s Violin Concerto in C, and Orchestral Trio in B‑flat, Op.1; Anton Filtz’s Violin Concerto in G; Ignaz Holzbauer’s Sinfonia Concertante in A and Sinfonia in E‑flat, Op.4; Christian Cannabich’s Sinfonia Concertante in C and Sinfonia in B‑flat; and Ludwig August LeBrun’s Oboe Concerto in D minor. Johann Stamitz, the effective founder of the school, stands out as the most immediately enjoyable in this set. His superb violin concerto merits comparison with Mozart’s. It’s loaded with virtuosity, simplicity, freedom and feeling, characteristics we associate with the next age. Tedious basso continuo and formal ornament are nowhere to be heard in it. I was also charmed by Cannabich and LeBrun’s warm oboe concerto. Other Mannheim composers of note, not represented in this set, were Franz Ignaz Beck, and Johann’s son Carl Stamitz.

Gabe Desrosiers’s round dance songs for jingle dress

The Jingle Dress dance is a women’s round dance which the Anishnaabe (Ojibway) of north-western Ontario take special pride in. “Jingle Dress” is the common term on the pow-wow circuit, but folks in the Kenora-Rainy River region of Ontario usually call it “medicine dress”. Gabe Desrosiers has composed numerous songs in honour of the Jingle Dress and the women who wear it. The songs are deeply rooted in northwest Ontario and Minnesota tradition, but these are modern songs. Desrosiers is accompanied by a solid team of drummers and singers from the Whitefish Bay and North West Angle #33 reserves, known as the Northern Wind. The Anishnaabe drumming style is characterized by sudden volume changes and caesura. Expect impromptu shouts, hoots and exclamations to be thrown in at psychologically apt moments, giving these dances sort of hot jazz sensibility. I don’t have the group’s award winning album Whispering Winds, but I can recommend my newly acquired Medicine Dress, which can be gotten from Arbor Records in Winnipeg. Read more »

Hossein Alizadeh and Djivan Gasparyan’s Endless Vision

This quite beautiful album of slow-paced, deeply romantic music combines the virtuosity of Djivan Gasparyan, the venerable master of the Armenian duduk, and Hossein Alizadeh, the superstar of the Persian tar. The duduk is a nine-holed oboe made of apricot wood, somewhat resembling the medieval European shawm, and Gasparyan is its unrivaled master. Alizadeh is the younger dynamo of the Persian lute. However, for this amazing performance recorded in Tehran in September of 2003, Alizadeh employed a variant form of the tar known as the shurangiz. The concert alternated Armenian and Persian songs, and included Alizadeh’s familiar orchestra, and three vocalists — one female, something considered a bit daring in contemporary, mullah-infested Iran. Iran and the United States share a common affliction: both are nations with a deep and multifaceted musical heritage, and an innate vitality of popular culture, which have the misfortune of being ruled by wicked, ignorant, stupid old men, and tormented by moronic religious zealots. Yet the underlying vitality and beauty always seems to survive. Relax with a book of verse, a cup of wine, and any agreeable thou at your disposal, and put on this album.

First-time listening for September, 2008:

18988. (Hugo Alfvén) Swedish Rhapsody # 2, Op.24, R58 “Uppsala”

18989. (Hugo Alfvén) Symphony #1 in F minor, Op.7, R 24

18990. (Hugo Alfvén) Drapa, Op. 27 “In Memoriam King Oscar II”

18991. (Hugo Alfvén) Uppenbarelsekantat “Revelation Cantata”, Op. 31: Andante religioso

18992. (Hugo Alfvén) Symphony #2 in D major, Op.11, R 28

18993. (Pixies) Wave of Mutilation: Best of Pixies

18994. (Zap Mama) Sabsylma

18995. (Hugo Alfvén) Swedish Rhapsody #3, R 120 “Dalarhapsodien”

18996. (Hugo Alfvén) Symphony #3 in E major, R 54

18997. (Hugo Alfvén) The Prodigal Son [Den forolade sonen], ballet suite, R 214

18998. (Ashley McIsaac) Helter’s Celtic

18999. (Arctic Monkeys) Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not

18900. (Gavin Taaffe) Sad Songs

19001. (Ornette Coleman) The Shape of Jazz to Come

A radio adaptation of The Day the Earth Stood Still

Radio drama continued longer than people generally imagine. Lux Radio Theatre’s last broadcast was on April Fool’s Day, 1954, and they chose a dramatization of the classic 1951 science fiction film, The Day the Earth Stood Still. Michael Rennie reprised his film role as the alien visitor Klaatu. Jean Peters performed the role taken by the husky-voiced Patricia Neal. From the voice, it sounds to me like Billy Gray also reprised his role from the film, as the curious young boy Bobby. His performance was critical to the film’s effectiveness, but this is seldom acknowledged. Gray went on to a solid film career as a supporting player, and some success as a speedway motorcycle racer and the inventor of the F‑1 guitar pick. The radio adaptation kept close to the film script, merely tweaking the lines when visual elements had to be evoked. Rennie sounded a little tired, but on the whole, it was a fine translation of the film into a different medium.

Gavin Taaffe: Sad Songs

It can be awkward to review an album when the musician is a personal friend, especially when one of the songs references events one has personally witnessed, but not in this case. The music speaks for itself. This compilation of songs composed over the last eight years confirms Gavin Taaffe’s status as an upcoming singer-songwriter worth comparing to Bruce Cockburn or Sufjan Stevens. The lyrics are intelligent, subtle, supple… and, yes, sad. You should have a taste for concentrated pessimism tempered by a sense of survival to enjoy them. Ineffable feelings of disappointment, loss, and longing are captured in crisp verbal images and piquant melodic phrases and guitar licks. Recommended for late-night listening.

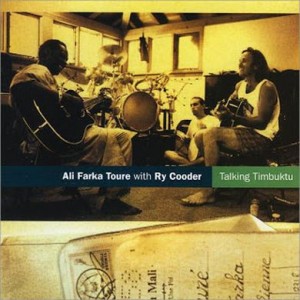

Ali Farka Touré and Ry Cooder Talking Timbuktu

I’ve written elsewhere of my love for the music of Ali Farka Touré, whose every chord calls back memories of the Sahara, and whose spirit hovered above Timbuktu like an angel. His was a profound and subtle art, which turned the “blues” into a clarion of sublime affirmation. His native Mali suffered the exploitation of dictatorship and the horrors of civil war, but he remained undaunted in his optimism. While other Malian musicians fled to Europe and America to pursue their careers, Touré stuck it out at home. The overthrow of dictatorship produced a renaissance of Malian music. Touré was the very solid rock on which that renaissance was founded. True to his character, he spent the last years of his life serving as mayor of a small village near Timbuktu, spending the money from his international recordings to provide it with sewerage and electricity. My favourite album of his will always be The Source (1993), but jostling against it for that position is this wonderful 1995 collaboration with American guitarist Ry Cooder, Talking Timbuktu. Unlike some of the rather patronizing duets between African artists and European or American superstars, this one is an easy-going session between two professional musicians who have little patience with stage-egos or manufactured images. Cooder is as American as they come, and Touré as African as they come, and both understood how those two places are musically and spiritually intertwined. America could not have become America without Africa. It would just have been one more place where they danced with wooden clogs in 4/4 time, and played the accordion. It could not have brought forth Ellington, Gershwin, Satchmo, Goodman and Chuck Berry and all that came from them. Listen to the marvelous performances of “Ai Du” and “Diaraby” on this album, and you’ll hear that brotherhood.

I’ve written elsewhere of my love for the music of Ali Farka Touré, whose every chord calls back memories of the Sahara, and whose spirit hovered above Timbuktu like an angel. His was a profound and subtle art, which turned the “blues” into a clarion of sublime affirmation. His native Mali suffered the exploitation of dictatorship and the horrors of civil war, but he remained undaunted in his optimism. While other Malian musicians fled to Europe and America to pursue their careers, Touré stuck it out at home. The overthrow of dictatorship produced a renaissance of Malian music. Touré was the very solid rock on which that renaissance was founded. True to his character, he spent the last years of his life serving as mayor of a small village near Timbuktu, spending the money from his international recordings to provide it with sewerage and electricity. My favourite album of his will always be The Source (1993), but jostling against it for that position is this wonderful 1995 collaboration with American guitarist Ry Cooder, Talking Timbuktu. Unlike some of the rather patronizing duets between African artists and European or American superstars, this one is an easy-going session between two professional musicians who have little patience with stage-egos or manufactured images. Cooder is as American as they come, and Touré as African as they come, and both understood how those two places are musically and spiritually intertwined. America could not have become America without Africa. It would just have been one more place where they danced with wooden clogs in 4/4 time, and played the accordion. It could not have brought forth Ellington, Gershwin, Satchmo, Goodman and Chuck Berry and all that came from them. Listen to the marvelous performances of “Ai Du” and “Diaraby” on this album, and you’ll hear that brotherhood.

Haydn’s Symphonies “A” and “B”

Since I found a set of scores for Haydn’s first fifty symphonies (published in Germany, and apparently withdrawn from the Mannes College of Music in New York City sometime in the 1960s), it behooves me to listen to them with score in hand. I’m not sure why the first two are not numbered, but labeled “A” and “B”, but I presume it’s because their attribution is doubtful. “B” certainly sounds like Haydn. “A” is plodding and mechanical, and could have been composed by anybody. The role of the composer in the first half of the 18th century was rather like that of a rave dj. He was expected to “spin” whatever was at hand, and much material was recycled from his own (or others’) output. Nobody kept track of who composed what, except as an after-thought. Composers where constantly fired and rehired by patrons, and hopping from one princely court to another created opportunities for purloining works, or rehashing one’s own. When necessary, baroque music could be manufactured in minutes, by assembling cookie-cutter patterns. Some baroque composers, like Giuseppe Torelli, seem to have “composed” more music than could be played end-to-end over their lifetimes. Someone used to the modern idea of a “symphony” would barely recognize these pieces as such. Later on, Haydn himself, and the young Mozart, would create the complex form of that name, by expanding the orchestration and creating structural unity beyond the mere lumping together of vaguely similar pieces. The symphonies of this period were what we would call “suites” today. But that doesn’t mean that they couldn’t be intelligent and entertaining.

First-time listening for August, 2008

18962. (Franz Josef Haydn) Symphony “A” in B‑flat [1762]

18963. (Franz Josef Haydn) Symphony “B” in B‑flat [1765]

(Ruth Golden, soprano) Silent Noon: Songs of Ralph Vaughan Williams

. . . . 18964. (Ralph Vaughan Williams) House of Life, Six Songs to Poems of Dante Gabriel

. . . . . . . . Rossetti for Baritone and Piano [arr. for soprano and piano] [see original at 16063]

. . . . 18965. (Ralph Vaughan Williams) Four Last Songs to Poems of Ursula Vaughan Williams

. . . . 18966. (Ralph Vaughan Williams) “Linden Lea”, song for voice & orchestra (“In Linden Lea”;

. . . . . . . . “A Dorset Song”) [arr. voice & piano]

Read more »