Swindells runs two stories in parallel. One is set in 19th century London, and tells of an orphan boy who encounters Dr. John Snow, the founder of modern epidemiology, and discoverer of the cause of cholera. The second story is set in modern times, and follows a young girl who flees sexual abuse from her mother’s boyfriend, and lives in a London “squat”. Interspersed through these episodes are newspaper letters from a conservative crank, and the diaries of a nasty Victorian magistrate. The boy’s narrative is written in phonetic transcription of his dialect, which may cause trouble for a Canadian or American reader. Juggling these disparate elements is a difficult task, and the author pulls it off beautifully. The novel has an obvious message: the struggle against ignorance never ceases. I was delighted that a youth novel like this draws attention to Snow, who is one of my personal heroes. The more attention is paid to really important historical personages like Snow, the more people will understand the difference between them and the assortment of gangsters, thugs, and con-men who are conventionally represented as “great”.

Category Archives: B - READING - Page 41

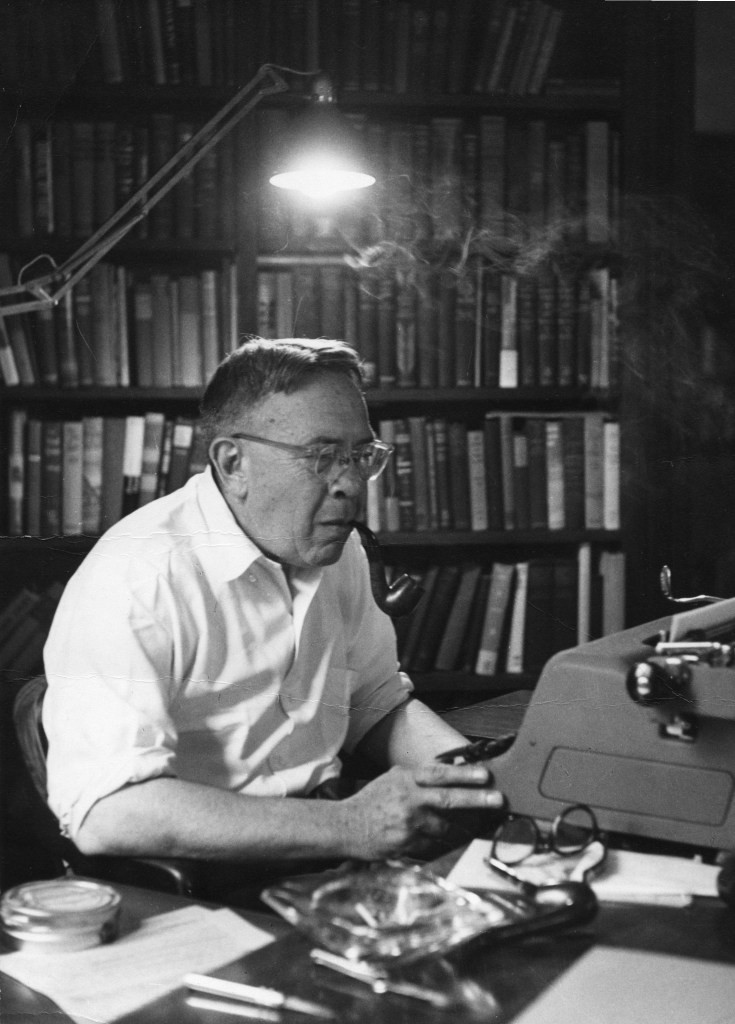

14716. (Bernard DeVoto) Mark Twain’s America

Bernard DeVoto was was one of the leading Mark Twain scholars, as well as being a historian of the American far west, a passionate advocate of nature conservation, and a leading advocate of civil liberties. In this curious book, written in 1932, he devotes most of his energy to criticizing other Mark Twain Scholars. The book is clever, acerbic, and sometimes downright nasty, but entertains precisely for those reasons. DeVoto detested the scholastic habits of reifying abstractions (The Frontier, Puritanism, The Artist, Materialism) and basing grand explanatory theories on trivial or dubious evidence, or no evidence at all. Sometimes his sarcasm grates on the reader, but often it is just so good (that is to say, cruel, like Scottish humour) that it brings up a smile from that little reservoir of malice that hides somewhere in even the kindest reader. Here is his treatment of one well-known pundit: “He exhibits the amateur’s reverence for the principle of ambivalence. This, in his lay psycho-analysis, is a device for the reconciliation of contradictory evidence. It explains that a fact can be both its literal self and a symbol of its opposite, that one fact can prove a given assertion on one page and a contradictory assertion on another, that the two facts which seem to indicate irreconcilable conclusions really mean one thing — the preferred thing.” Boy, I wish I could write sarcasm of that distillation. DeVoto could probably take on six coral snakes and a grizzlie before breakfast, then move on to serious sarcasm after coffee. Psychoanalytic criticism was the babble of that time, but I’m sure he would make mincemeat of today’s equivalents (“post-modernism”, for example).

Bernard DeVoto was was one of the leading Mark Twain scholars, as well as being a historian of the American far west, a passionate advocate of nature conservation, and a leading advocate of civil liberties. In this curious book, written in 1932, he devotes most of his energy to criticizing other Mark Twain Scholars. The book is clever, acerbic, and sometimes downright nasty, but entertains precisely for those reasons. DeVoto detested the scholastic habits of reifying abstractions (The Frontier, Puritanism, The Artist, Materialism) and basing grand explanatory theories on trivial or dubious evidence, or no evidence at all. Sometimes his sarcasm grates on the reader, but often it is just so good (that is to say, cruel, like Scottish humour) that it brings up a smile from that little reservoir of malice that hides somewhere in even the kindest reader. Here is his treatment of one well-known pundit: “He exhibits the amateur’s reverence for the principle of ambivalence. This, in his lay psycho-analysis, is a device for the reconciliation of contradictory evidence. It explains that a fact can be both its literal self and a symbol of its opposite, that one fact can prove a given assertion on one page and a contradictory assertion on another, that the two facts which seem to indicate irreconcilable conclusions really mean one thing — the preferred thing.” Boy, I wish I could write sarcasm of that distillation. DeVoto could probably take on six coral snakes and a grizzlie before breakfast, then move on to serious sarcasm after coffee. Psychoanalytic criticism was the babble of that time, but I’m sure he would make mincemeat of today’s equivalents (“post-modernism”, for example).

14715. (Jung Chang) Mao, the Unknown Story

There’s a common belief, fostered in gentle societies, where people expect their children to grow up, and famine never stalks the land, that there is no such thing as absolute evil, and that dictators are confused idealists who took a wrong turn. This, the first seriously researched and accurate biography of Mao Zedong, should disabuse anyone of such naivité. I have spent most of my lifetime studying the motives, ideologies, mechanisms, and agents of slavery, but I was still not prepared for the contents of this book, which is one of the most important biographies of modern times. It is absolutely essential that this book be in every library and school in the world, for Holocaust Denial is the endemic sickness of our age, and the worship of mass murderers the endemic sickness of all ages.

There’s a common belief, fostered in gentle societies, where people expect their children to grow up, and famine never stalks the land, that there is no such thing as absolute evil, and that dictators are confused idealists who took a wrong turn. This, the first seriously researched and accurate biography of Mao Zedong, should disabuse anyone of such naivité. I have spent most of my lifetime studying the motives, ideologies, mechanisms, and agents of slavery, but I was still not prepared for the contents of this book, which is one of the most important biographies of modern times. It is absolutely essential that this book be in every library and school in the world, for Holocaust Denial is the endemic sickness of our age, and the worship of mass murderers the endemic sickness of all ages.

I remember when college campuses were adorned with posters of Mao, when Jean-Paul Sartre was proclaiming that Mao’s “revolutionary violence” was “profoundly moral”, when university professors prattled the moronic, megalomaniac slogans of Mao’s Little Red Book [“Power comes from the muzzle of a gun”] as if they were profound philosophy, and a lawyer and feminist activist tried to slap me in the face when I told her that Mao was a genocidal criminal. I remember when another student activist gleefully showed me a photograph of one of Mao’s “projects” — thousands of ragged, starved, brutalized slaves digging up earth with their bare hands while machine-gun-toting Communist Party cadrés watched over them, smoking cigarettes, barbed wire and wooden watchtowers clearly visible in the background. This, he explained, was the ideal society, Utopia being constructed for the common good. This was not even the death camps or the laogai, mind you, of which no pictures where permitted to exist, but of one of the projects the Party liked to publicize. And their calculations were correct. To the campus intellectuals in Paris, Berkeley, or Toronto, such pictures were appealing. To any actual human being, they could not be anything but horrifying and disgusting. Read more »

14706. (N. A. M. Rodger) The Command of the Ocean ― A Naval History of Britain, Volume Two, 1649–1815

The two hefty volumes of Rodger’s history of the British Navy bring the story only up to 1815. But this lifetime scholarly work is well-balanced with readability. Rodger thinks strategically more than tactically. He knows that the economics of getting ships on the sea, administering and supplying them, and making sure they do something useful is the heart of the matter. Britain had exercised considerable sea power in the northern world in Anglo-Saxon times, but the land-lubbing, horse riding Norman aristocracy used ships very crudely. Even in the Renaissance, there was no real “navy”, but merely inconsistent attempts to put together fleets for various temporary purposes, and naval tactics remained primitive. Henry VIII was particularly irresponsible and destructive, as he was with everything else. Elizabeth’s reign was dominated by “privateering”. It was only during Cromwellian times, when the ruling dictatorship feared disloyalty among seamen, that the first attempts were made to organize and administer what would fit our modern notions of a national navy. Much of the story, of course, involves the more economically advanced Dutch, with whom British political, military and economic relations were interwoven for centuries. Rodgers is very adept at sorting out these complexities.

14698. (Raymond W. Baker) Capitalism’s Achilles Heel: Dirty Money and How to Renew the Free-Market System

This book, by the authoritative expert on global money laundering, outlines the involvement of the governments, corporations, and banks in the processing of criminal money on a vast scale. But he is more concerned with the system of false bookkeeping with which the world’s poorest regions are systematically drained of capital. Baker is no philosophical lightweight: he remains trapped in a false system of definitions and terminology, but he knows that there is something wrong with it. He correctly points out that the current Conservative ideology of global finance has nothing to do with Adam Smith’s theories of free markets, which it violates in every particular, but is descended, instead, from the moral blankness of Jeremy Bentham’s platophistries. But he cannot pull himself out of his received framework to make the necessary next steps in analysis. There is no doubt, however, of his basic decency..

14697. (Jon George) Faces of Mist and Flame

A very good show for a first novel: A young prodigy at Cambridge uses her discovery of bodiless time travel to enter the mind of a young American soldier at the invasion of Guam during World War II. The story is told in parallel with the classical Greek myth of the Labours of Hercules, and also draws on the native folklore of Guam. George pulls you into the story quickly and treats his characters with sensitivity. I especially respect this kind of work because it requires real research to pull off. Getting things right, historically, psychologically, and culturally, has not been a big goal in the big SF publishing houses, lately, and this is an encouraging exception. I found only a few choices of words that I would quibble with.

READING – JUNE 2006

14673. (Anthony Boucher) The Case of the Seven Sneezes

14674. (Marshall McLuhan) The Gutenburg Galaxy

14675. (Gerald Posner) Secrets of the Kingdom ― The Inside Story of the Saudi‑U.S. Connection

14676. (Evangeline Walton) The Children of Llyr

14677. (Nancy Phelan & Michael Volin) Sex and Yoga

14678. (Jared Diamond) Guns, Germs and Steel

Read more »

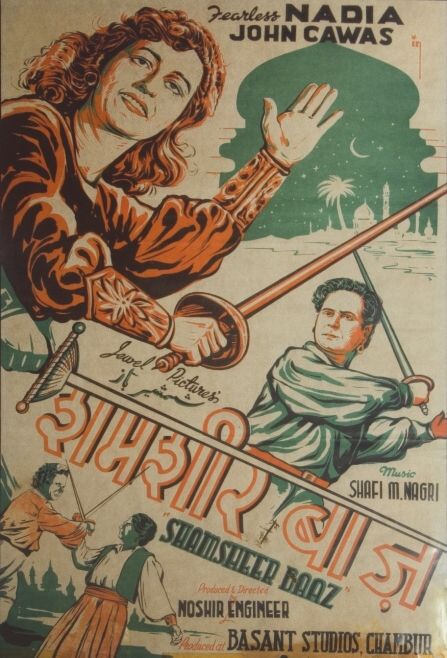

14694. (Shoma A. Chatterji) Subject: Cinema, Object: Woman, a Study of the Portrayal of Women in Indian Cinema

Who would have guessed that, as early as the 1930’s, there was an action heroine in Indian cinema, who did all her own stunts, and defied all the conventions of passive and simpering femininity, and played second fiddle to no male? That’s the most remarkable information in this study. Starting with Hunterwali (1935), Fearless Nadia starred in a series of extremely popular adventure films. “The female protagonist entered the scene on horseback, with the clarion call of ‘Hey-y-y‑y’, hand raised defiantly inn the air, riding in with the pride and arrogance that was more befitting of Douglas Fairbanks.” This remarkable actress had started out as a steno-typist, but, inclined to be plump, took dancing lessons. Then she joined a traveling circus, and a ballet troop. Her amazing film stunts (all real) included hoisting strong men on her back, fighting four lions, swinging from chandeliers, leaping from cliffs into waterfalls. She rode, swam, tumbled, wrestled and fenced her way through numerous films, often with a mask and a whip, until she was nearly fifty.

Who would have guessed that, as early as the 1930’s, there was an action heroine in Indian cinema, who did all her own stunts, and defied all the conventions of passive and simpering femininity, and played second fiddle to no male? That’s the most remarkable information in this study. Starting with Hunterwali (1935), Fearless Nadia starred in a series of extremely popular adventure films. “The female protagonist entered the scene on horseback, with the clarion call of ‘Hey-y-y‑y’, hand raised defiantly inn the air, riding in with the pride and arrogance that was more befitting of Douglas Fairbanks.” This remarkable actress had started out as a steno-typist, but, inclined to be plump, took dancing lessons. Then she joined a traveling circus, and a ballet troop. Her amazing film stunts (all real) included hoisting strong men on her back, fighting four lions, swinging from chandeliers, leaping from cliffs into waterfalls. She rode, swam, tumbled, wrestled and fenced her way through numerous films, often with a mask and a whip, until she was nearly fifty.

14693. (Walter Mosley) 47

I’ve been remarking that some of the best written books, in recent times, have been published in the “juvenile” market. This book proves my point. It’s a beautifully written, emotionally powerful, and highly imaginative demonstration of what it means to be a slave. No topic is closer to my heart, and, frankly, I wish that I had written this book. “47” is a plantation slave, who, in the 1830’s, encounters an alien being who is stranded on earth. He tells his tale from the viewpoint of now, since he has become effectively immortal, and still retains the 14-year-old body. But the science fiction element of the story is underplayed. Mosley concentrates on making the reader hear, taste, smell, and feel the reality of slavery. It’s a fine piece of work.

(J. R. R. Tolkien) Tree and Leaf

The first item, the essay “On Fairy Stories”, is essential reading for anyone with a serious interest in Tolkien. It makes clear exactly what he was doing, and why. It was written during the height of the dominant position of “realism” in literature, when anything even remotely imaginative was considered trash by literary people. Tolkien was particularly annoyed by those who saw fantasy, especially the particular kind of fantasy that he called “fairy-story”, as exclusively for children. He writes:

Among those who still have enough wisdom not to think fairy stories pernicious, the common opinion seems to be that there is a natural connexion between the minds of children and fairy-stories, of the same order as the connexion between children’s bodies and milk. I think this is an error; at best an error of false sentiment, and one that is therefore most often made by those who, for whatever private reasons (such as childlessness), tend to think of children as a special kind of creature, almost a different race, rather than as normal, if immature, members of a particular family, and of the human family at large. Actually, the association of children and fairy-stories is an accident of our domestic history. Fairy stories have in the modern world been relegated to the ‘nursery’, as shabby or old-fashioned furniture is relegated to the play-room, primarily because adults do not want it, and do not mind if it is misused.

Touché. I can still remember when that attitude was gospel, when a good science fiction writer like Kurt Vonnegut had to vociferously deny that he wrote SF so he could be taken seriously, and the encyclopedias described H. G. Wells as the author of Tono Bungay, Mr. Brittling Sees It Through, and, embarrassingly, “some scientific romances”.

contents:

14691. [2] (J. R. R. Tolkien) On Fairy Stories

14692. [3] (J. R. R. Tolkien) Leaf by Niggle