Before I could even read and write, I drew maps. The desire to create a visual model of my physical environment seems to have been built into me. Throughout childhood, I drew maps of the nearby forests, carefully pacing out trails in order to reproduce their proportions correctly, and marking down swamps, cliffs, and glacial boulders. When I became aware of the existence of published maps and atlases, I pored over them with the enthusiasm that other kids had for hockey cards and comics.

Before I could even read and write, I drew maps. The desire to create a visual model of my physical environment seems to have been built into me. Throughout childhood, I drew maps of the nearby forests, carefully pacing out trails in order to reproduce their proportions correctly, and marking down swamps, cliffs, and glacial boulders. When I became aware of the existence of published maps and atlases, I pored over them with the enthusiasm that other kids had for hockey cards and comics.

I was not, however, destined to be an “armchair traveler”. Maps, for me, were ― and remain ― an expression of an impatient restlessness that is the signature of my temperament. Wanderlust. Itchy feet. A chronic chafing against any confinement or restraint. It’s not surprising that my intellectual interests combined geography and history with the philosophical issues of freedom and slavery.

To me, a life without travel would be pointless. Thus, at the first opportunity, I began a peripatetic existence that led me to experience many wondrous and beautiful things, but left me with no established career or financial security. I still can’t claim either “success” or “normalcy”. I’ve had many adventures, and close scrapes, and while these make interesting memories, too much can be made of them. I would like, right here, to make an important distinction between the psychology of the adventurer and that of the explorer. I fit into the second category, and not at all into the first.

The adventurer is a thrill-seeker. He or she seeks out danger for the sake of danger itself, excitement for the sake of excitement. That’s nothing like me, at all, for I have a rather placid temperament. I find danger distressing, and the rush of adrenalin extremely unpleasant. Occasionally, I’m tempted to boast about adventures, especially when confronted with my blatant lack of material success, but the reader will surely recognize that as a defensive strategy. No, the word “explorer” suits me much better, especially since it encompasses time spent in a library, poring over books, as much as time spent on a camel or a burro. The focus of the explorer is on finding out, uncovering what is hidden, delighting in the new. Adrenalin doesn’t matter.

But “finding out” is not, for me, a matter of second-hand experience or of mastering summaries, redactions, or abstractions. It has to be direct, and sensory, to appeal to me. I can never be content to merely read about a waterfall, a ruined city, a desert dune, a cathedral, or a crowded souk. I must be there. I must touch and smell them. Pink and golden Sahara sand smells like no other sand, and I need to know that smell. I need to hear the sounds, feel the wind, experience the dampness or the roughness. Texture is what matters to me.

My interest in history is more or less a side effect of my delight in place and texture. Every place has its history, and the dimension of time is part of the texture of specific places. When I see a snake-shaped mound of earth on the shore of an Ontario lake, it is an essential adjunct to the direct sensory experience to know that it was put there by the Point Peninsula people, two thousand years ago, with some relation to the Hopewell Culture of the Ohio Valley, and not by, say, the Ontario Department of Highways in 1968. It is also essential to me to know precisely how it may be, or may not be, connected to the Hiawatha First Nation whose property it rests on, and what the best guesses might be as to the meaning of the nearby petroglyphs. That, in combination with the smell of the moist earth, and the slapping of the waves against my canoe, as I approach the site, and the honking of geese and the chill of the air, forms the whole experience. Seeking out that experience is the thrill of exploration. But it is not “adventure”. I can reach the serpent mound in a single day trip from my apartment, with no danger and little discomfort, but it is every bit as much an act of exploration as a journey to a remote and dangerous place.

But I can never be content with only seeing those things which are accessible to me here in Toronto. They give me pleasure, but being confined to one place alone is a torment to me. There is a huge world out there, and while I’ve seen many things and poked around three continents, the list of things that I simply must see for myself is very long, and the biological clock ticks away relentlessly. I don’t want to end up inching toward Macchu Picchu leaning on a “walker”. I don’t want to die without seeing the Gopurams of Tamil Nadu or the wind sweeping across the Altai, or the Tepuis of the Upper Orinoco. I can’t think of any material success that would compensate for missing out on these things. The ability and opportunity to experience them would be my definition of material success.

At the moment, I’m engaged in researching and writing on a specific issue involving the organization of the Métis buffalo hunt in 19th century. Most of the work involves reading primary sources from the era, and some from the century before (I am trying to uncover some suspected continuities). I can only do this, and would only want to do this, with the memory of the musky, overpowering smell of buffalo in my mind, of the flavour of saskatoonberries pounded into brittle pemmican, and of the pow wow songs of the Plains acting as ghostly attendants to the work.

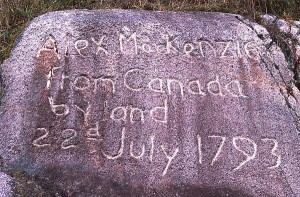

I’m reading the journal of Alexander Mackenzie [1] , whose explorations of Canada’s west and the Arctic were on a spectacular scale. Born in the Gaelic-speaking Outer Hebrides of Scotland, he began working for Montreal fur traders at the age of fifteen, and at twenty-five undertook the journey down the mighty river that now bears his name, to the Arctic Ocean. On a later, equally astonishing journey, he found a way across the Rockies to the Pacific — long before Lewis and Clark. Mackenzie appears to have been something of a physical superman, judging by some of his feats, and in that I can claim no resemblance. But in other ways, the man strikes me as a kindred spirit. Mackenzie recorded every sight, sound, and smell with incredible vividness and accuracy. For one stretch of a couple of hundred kilometres, I was able to deduce his exact location at every point, and recognize every landmark from my own personal knowledge, even though all the names attributed to the various natural features have since changed, without having to consult a map. His observations and interactions with the people of the land, for many of whom he was the first European they had encountered, display a remarkable sensitivity and objectivity. A modern cultural anthropologist would be hard pressed to match his insight and observational skill with native societies. He was fluent in several Native Canadian tongues. Incredibly, he was able to accurately deduce the exact relationships and family groupings of dozens of languages, without any training in philology or descriptive linguistics (sciences which, at any rate, hardly existed at the time). The journal includes several comparative word lists with which he demonstrates these relationships. The historians who have recounted his exploits have not, apparently, grasped the astonishing nature of this achievement. His observations of natural history, native economics, political situations, and of personal character all show keen judgment, though his formal education consisted of a year of grammar school in Montreal. Nothing compelled him to notice any of these things ― his employers wanted little except to fill in some blank spaces on the map, and they ignored most of his practical advice.

I’m reading the journal of Alexander Mackenzie [1] , whose explorations of Canada’s west and the Arctic were on a spectacular scale. Born in the Gaelic-speaking Outer Hebrides of Scotland, he began working for Montreal fur traders at the age of fifteen, and at twenty-five undertook the journey down the mighty river that now bears his name, to the Arctic Ocean. On a later, equally astonishing journey, he found a way across the Rockies to the Pacific — long before Lewis and Clark. Mackenzie appears to have been something of a physical superman, judging by some of his feats, and in that I can claim no resemblance. But in other ways, the man strikes me as a kindred spirit. Mackenzie recorded every sight, sound, and smell with incredible vividness and accuracy. For one stretch of a couple of hundred kilometres, I was able to deduce his exact location at every point, and recognize every landmark from my own personal knowledge, even though all the names attributed to the various natural features have since changed, without having to consult a map. His observations and interactions with the people of the land, for many of whom he was the first European they had encountered, display a remarkable sensitivity and objectivity. A modern cultural anthropologist would be hard pressed to match his insight and observational skill with native societies. He was fluent in several Native Canadian tongues. Incredibly, he was able to accurately deduce the exact relationships and family groupings of dozens of languages, without any training in philology or descriptive linguistics (sciences which, at any rate, hardly existed at the time). The journal includes several comparative word lists with which he demonstrates these relationships. The historians who have recounted his exploits have not, apparently, grasped the astonishing nature of this achievement. His observations of natural history, native economics, political situations, and of personal character all show keen judgment, though his formal education consisted of a year of grammar school in Montreal. Nothing compelled him to notice any of these things ― his employers wanted little except to fill in some blank spaces on the map, and they ignored most of his practical advice.

You get the overwhelming impression that the man was thoroughly enjoying himself.

Alexander Mackenzie (actually, Alasdair MacCoinnich in Gaelic) speaks to me through his journal, because I sense a similar attitude to my own. The itchy feet, the restlessness, the impatience with authority, combined with a craving to observe detail, all resonate with me. Unlike his fellow explorer, David Thompson (who ended up forgotten, pawning his sextant to feed himself), Mackenzie at least managed to parley his achievements into a modestly successful retirement. Let’s hope that I can manage the same trick.

[1] Voyages from Montreal, on the river St. Laurence, through the continent of North America, to the Frozen and Pacific oceans; in the years, 1789 and 1793; with a preliminary account of the rise,progress, and present state of the fur trade of that country. M.G. Hurtig Ltd., Edmonton — facsimile of the William Combe edition of 1801.

0 Comments.