Almost every day, I walk past two spots of historical interest on King Street, here in Toronto. They are only a block apart, but they represent the moral nadir and zenith of the city’s history.

The first is only a dusty bronze plaque mounted on the side of an old office building. It marks the place where, in 1798, Toronto’s first jail was built. Since it was known as the “old log jail”, we can guess the kind of public structures that graced the streets of what was then known as “Muddy York,” and reclaimed its Iroquoian name of Toronto only in 1834. The plaque makes note of the fact that the first execution took place on October 11th, 1798, when one John Sullivan was hung by the neck until dead, for the crime of stealing a note worth approximately one dollar.

This little addendum tells us more about the nature of the era than a library of history books and encyclopedias. We tend to assume that we must delve into remote antiquity to find a barbaric human nature, devoid of morality. However, I need only walk a half mile from my home to find evidence of a sadistic and savage human race dwelling in my own city, only two short centuries in the past. That a man could be hung for a dollar tells all that one needs to know. One can easily picture the scene. York, a squalid little village newly built and garrisoned as a bulwark against invasion from the United States, its streets calf-deep in sticky mud, made aromatic by the shit of the hundreds of semi-feral pigs that roam untended. Execution for petty property crimes is the norm, and the “drop” will not be adopted until the 1870’s. Slow, agonizing torture is part of the whole entertainment, considered suitable and even educational for children. In the jail-yard, a jeering and laughing mob waits for the thrill of seeing John Sullivan slowly strangle, anticipating the hilarity of seeing his eyes bulge and tongue turn blue, his neck stretch like taffy, and, hopefully, for him to soil himself. More dignified, but equally amused, are the city’s elite: military officers, wealthy merchants, pious clergymen. All are sublimely confident of their righteousness. And they are proud of being progressive. It is, after all, not like Old England, where an eleven year old girl might be hung for the theft of a spoon, and magistrates would proclaim the just necessity of it with all the same arguments that Conservatives use to defend the death penalty in 2009. No, they don’t hang children in Muddy York, but a theft of a dollar is another matter. Justice must be done.

By 1870, the authorities came to see the public delight at executions as something embarrassing, and the sacrificial ceremonies were withdrawn into the courtyard of a newer jail. Canada maintained a professional executioner on the Federal payroll. John Radclive, the first such official, executed 150 people between 1892 and his death from alcoholism in 1911. The last three people executed in Toronto (and in Canada) were Ronald Turpin, Arthur Lucas, and Jay Nickerson, in 1962. The death penalty was abolished de facto in 1963 and de jure in 1976. The current Conservative federal government, of course, keeps the barbarians’ pornographic dream alive, always hoping that it can re-instate the practice.

On the same block, in the 1870’s, an anti-Catholic mob, led by the unspeakably evil Orange Order that long controlled the politics of the city, attempted to burn down St. Patrick Hall, in a blood lust to kill a guest speaker of the Irish Catholic Benevolent Union.

Adjacent to the site of that terpitude, there is something altogether more inspiring, which holds a special significance for me.

When I first began to read seriously in history, as a boy, my instincts led me to avoid looking for heroes. Trying to find people in the past to admire and respect can be a trap. One is bound to be disappointed. The sad truth is that scoundrels and monsters routinely find their way into history books, but good people do not. The very fact that one is a decent human being virtually guarantees that one will be forgotten. Historical figures propped up as models or champions of this and that usually turn out to be outright frauds, or at the very least to have genuine accomplishments marred by major flaws. But there was one historical figure that I could not help admiring, and that was Frederick Douglass, whose Autobiography inspired me from childhood. And I did not know until recently that I could walk on the very floor where Douglass walked and spoke, right near my own home.

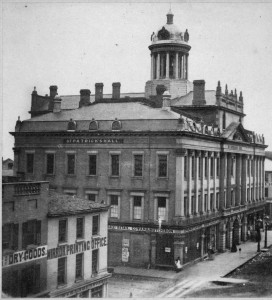

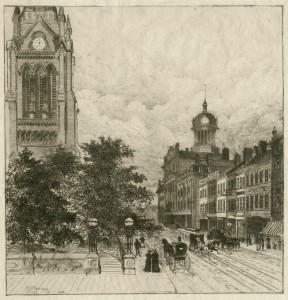

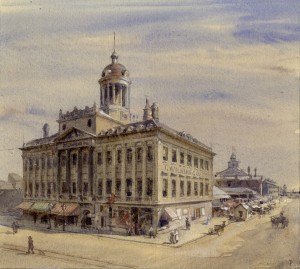

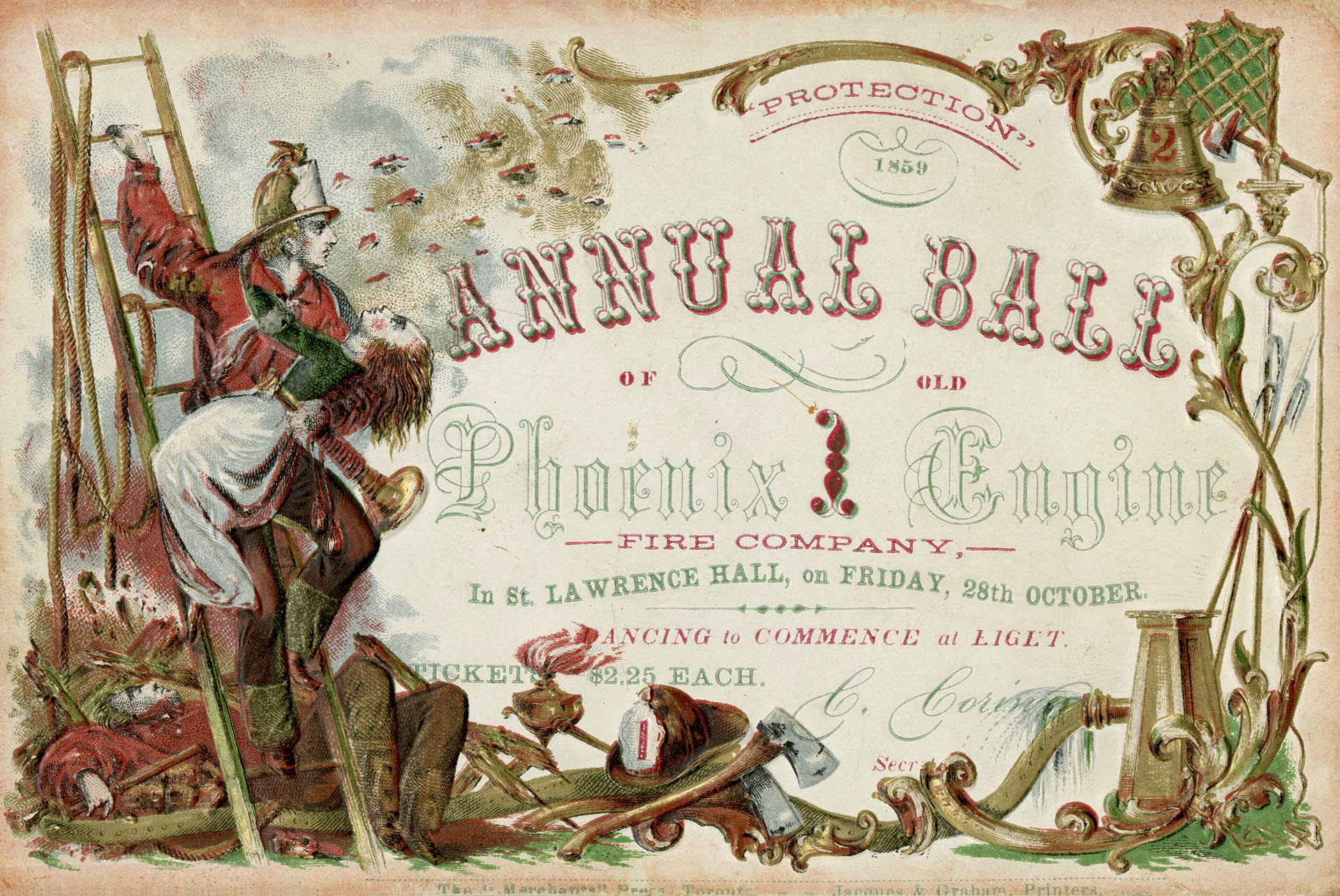

At the corner of King and Jarvis stands St. Lawrence Hall. This fine structure was built in 1850 to provide a venue for public meetings, concerts, balls, and other cultural events of the little city that was then maturing out of its crude frontier beginnings. Over the next century, the hall would be used to echo the voice of Jenny Lind, display the curios of P.T. Barnum, and be used as a practice dance hall by Rudolf Nureyev and Margot Fonteyn. The structure is well preserved, and an excellent example of the Renaissance Revival style of the mid-nineteenth century. Unlike most such structures, it has maintained its intended function throughout its existence.

The timing of its construction was propitious, for there was an important issue for public discussion: the recently enacted Fugitive Slave Law in the United States. This law allowed agents from the southern slave states to conduct a reign of terror in northern states, kidnapping runaway slaves, and many free blacks, and dragging them back to the slave pens of the south. It effectively unleashed the tentacles of the monstrously evil institution of slavery throughout the United States, canceling out existing abolitionist reforms. This hideous injustice would soon lead the United States into a bloody civil war. The activities of the Underground Railroad, the organized resistance movement which smuggled escaped slaves to freedom in Canada, were now much more dangerous. Upper Canada had enacted legislation for the abolition of slavery in 1793. On the issue of slavery, Canadians were consistently and adamantly on the side of the angels. The Underground Railroad terminated in Toronto. Escaped American slaves formed free agricultural communities scattered around rural Ontario, and much of the resistance was organized here.

The timing of its construction was propitious, for there was an important issue for public discussion: the recently enacted Fugitive Slave Law in the United States. This law allowed agents from the southern slave states to conduct a reign of terror in northern states, kidnapping runaway slaves, and many free blacks, and dragging them back to the slave pens of the south. It effectively unleashed the tentacles of the monstrously evil institution of slavery throughout the United States, canceling out existing abolitionist reforms. This hideous injustice would soon lead the United States into a bloody civil war. The activities of the Underground Railroad, the organized resistance movement which smuggled escaped slaves to freedom in Canada, were now much more dangerous. Upper Canada had enacted legislation for the abolition of slavery in 1793. On the issue of slavery, Canadians were consistently and adamantly on the side of the angels. The Underground Railroad terminated in Toronto. Escaped American slaves formed free agricultural communities scattered around rural Ontario, and much of the resistance was organized here.

So it’s not surprising that Frederick Douglass came to Toronto, and spoke at the newly-built St. Lawrence Hall to a cheering crowd of 1,200 on April 3, 1851[1]. Yesterday, I entered the building, and walked through the empty hall, which has not much changed in general appearance.

Since I acknowledge so few heroes from the annals of history, I rarely get that special thrill that historians can enjoy… the pleasure of planting one’s feet on a spot trod by a paladin. I once stood rapt with pleasure in front of Mozart’s house, listening to one of his arias being sung. But Mozart’s is an example of a tragic life, transcended by genius, and can hardly serve as an example to follow. I have no transcendent genius of my own, so his example is useless to me, personally.

But the work of Frederick Douglass has long been, for me, a kind of guidebook in the quest for freedom and human dignity. The man was a genius, no doubt about it, but it was a real-world genius. He started as a slave, a chattel, and freed himself. In the process, he became the spokesman of all slaves, and the champion of all who suffer injustice. His Autobiography reveals a profound spiritual depth, a sophistication far beyond the vapid and overpraised intellectual “giants” of his time. There are many figures from the nineteenth century who are paraded through the history books as geniuses and heroes. At the very bottom, morally and intellectually, would be Karl Marx, whose moronic racist and genocidal rantings sickened me when I first read them, roughly at the same time I was being inspired by the nobility of Douglass’ work. Marx is immensely more famous than Douglass, but Douglass is a hundred million times more worthy of respect. But it is the nature of the human race to worship turds… that is why there is slavery in the world, in the first place. That’s why Douglass’s work meant so much to me. Yet he was a real, earthly man, with vanities and foibles. If I were to meet him, I would no doubt argue with him over some issues, perhaps grow impatient with his shortcomings, but I would always respect him. I was, in a way, one of the people he gave freedom to, and I will always be grateful.

Toronto’s history is so uneventful, by most standards, that it is hard to remember that the the past is real. My friend Filip Marek, in Prague, can every day walk across the Charles Bridge, and experience a sort of fast-rewind of spectacular incidents from the history books, each leaving a mark in stone for him to touch and see. The highlights in Toronto’s history are somewhat less exciting ― a comical little uprising against British rule in 1837, a few embarrassing incidents like the above-mentioned mob, and decade after decade in which the principle “historic events” were hockey games. These have left few physical reminders. For more than a century, nothing has happened here other than people getting up in the morning, going to work, raising kids, playing hockey, and having a cold bottle of beer and a barbecued hot dog in the back yard on a hot summer day. Millions came here, from every war-torn corner of the globe. Now Toronto is the most diverse metropolis on Earth, with more than half of it’s population born outside the country (twice the proportion of New York). Every language is spoken, every religion professed, every appearance shown. And they all choose to work and raise their kids in much the same way as their predecessors, without rancour. Only the food on the barbecues has changed.

When Frederick Douglass spoke in St. Lawrence Hall, in 1851, he could not have guessed that this would be the future of the little town, which may have been a haven for runaway slaves, but was wracked with infantile religious quarrels and ruled by pompous hypocrites. Nor could he have guessed that more than a century and a half later, someone would press his hands on the paneled wall of St. Lawrence Hall, and be grateful that it still stood, merely because his noble words had echoed upon them.

Toronto’s great meeting hall and one of its most important historic buildings opened on April 1, 1851, with a lecture entitled “Slavery” delivered by a British Member of Parliament. Later that year, St. Lawrence Hall hosted the historic North American Convention of Colored Freemen, where abolitionist leaders such as Frederick Douglass and Henry Bibb discussed the resettlement of refugees from American slavery. The Toronto convention offered African American leaders a safe haven to meet publicly with abolitionists from Canada, the United States and Britain without fear of violent reprisal.

— James Marsh Toronto In Time

[1] Toronto’s population was then 30,000.

0 Comments.