Farley Mowat engaged in some unrestrained speculation with his “Alban” prehistoric explorers. Now, Gavin Menzies goes absolutely wild with speculation in his “reconstruction” of a gigantic global exploration by the Chinese admiral Zheng He in the year 1421.

Farley Mowat engaged in some unrestrained speculation with his “Alban” prehistoric explorers. Now, Gavin Menzies goes absolutely wild with speculation in his “reconstruction” of a gigantic global exploration by the Chinese admiral Zheng He in the year 1421.

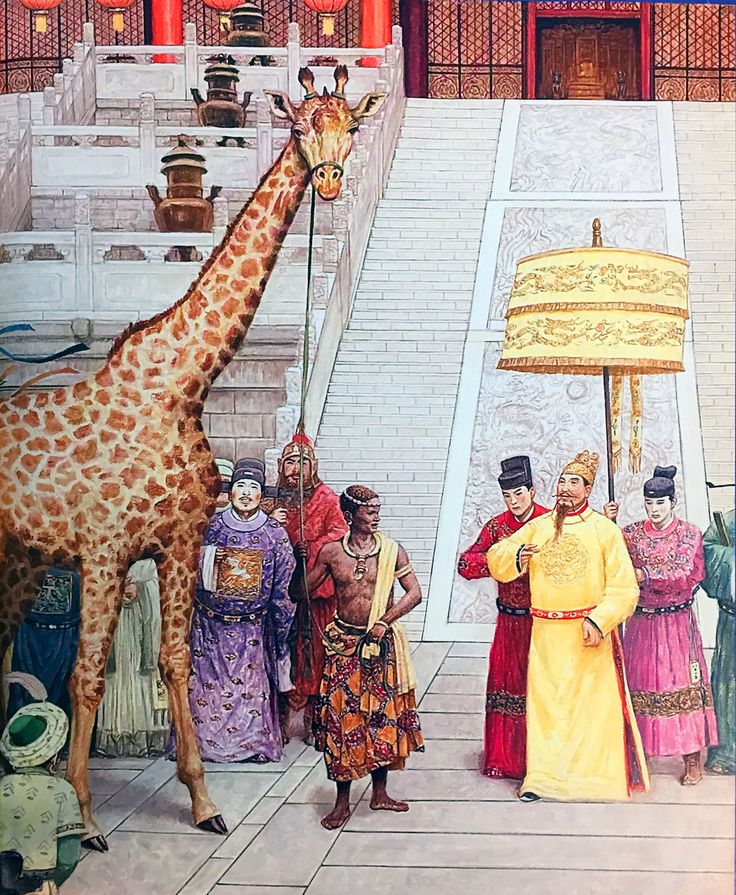

It is well known that a large Chinese Imperial fleet, under the direction of Zheng He (or Heng Ho), the eunuch aide-de-camp of the early Ming emperor Zhu Di, undertook seven long voyages that combined trade, diplomatic and exploratory motives. Chinese trade and exploration of the East African coast is well accepted by historians. Zheng He’s voyages are well documented by his secretary, Ma Huan, whose chronicling of some of the voyages was widely printed and distributed, and there are collateral accounts by Fei Xin and Gong Zhen, both officers on some of the voyages. There is also plenty of corroboration in Ming dynasty public records. Zheng He’s celebrity was such that plays were being performed about him while the voyages were still going, and a century and a half later, an immensely popular historical novel, Journey of the Three-Jeweled Eunuch to the Western Oceans by Luo Maodeng, retold the story with embellishments.

There is plausible archaeological evidence of a Chinese presence in Australia from even before Ming times. There is also little doubt that, in the fifteenth century, the Ming empire was the most technologically advanced region on earth, and that Chinese ships and navigators were capable of going pretty much anywhere if they had a mind to it. Chinese trade and exploration came to a sudden halt just around the time that Europe burst out of its constraints, as Confucian intellectuals forcibly shut it down in one of those frenzies of xenophobia that periodically overtake Chinese empires. There is also good reason to believe that European explorers were making use of earlier Chinese maps that revealed that Africa was circumnavigable, and perhaps some knowledge of the Western Hemisphere. In addition to all this, there are plenty of stray bits of puzzling data, odd archaelogical finds, odd coincidences, and little mysteries that might be explainable by Chinese contact with the New World. However, most of these tid-bits come with counter-evidence or reasonable doubt. Why, for instance, would Chinese cultural influence bring to pre-Columbian Mexico an elaborate set of techniques for making lacquerware, but not impart something obvious like the wheeled vehicle?

These are the starting points for Menzies’ book. Nothing is actually impossible about the vast circumnavigation of the globe, combined with exploration of the Arctic and Antarctic that Menzies adds to the known accomplishments of Zheng’s fleet. But Menzies “reconstructs” them entirely from post-Columbian maps and his real experience navigating submarines in the same waters. His argument that most of these maps had to have drawn from fifteen century Chinese maps is not convincing. For example, a much publicized map which was discovered in 2001 shows the world much as we know it, with the Western Hemisphere fairly correct. While text on the map indicates it was drawn in 1763, it claims to be a copy of another map drawn in 1418 made by or owned by Zheng He. It doesn’t take much of detective to notice that all the errors in it are exactly the errors found on contemporary maps in the 18th century, and that it can’t possibly reproduce a map from Zheng’s era.

That the Chinese of the Ming era had better knowledge of the world than Europeans of the time, is not in doubt. But most of Menzies’ “reconstruction” of specific, day-by-day comings and goings of Zhengs fleet (which for some reason were not mentioned in the detailed literature of his voyages), with every landfall and discovery conveniently attested by dubious circumstantial evidence, I don’t swallow. Most of the speculative leaps in each chapter depend on one accepting the truth of the speculative leaps made in the previous chapter. The logic runs like this: It’s known that I can jump a distance of three feet. So it’s plausible that I might be able to jump four feet. Accepting the premise that I can jump four feet, wouldn’t it be plausible that I can jump five? And accepting that, wouldn’t be plausible that I can jump six? This continues until I am theoretically jumping twenty feet, or a hundred feet. Menzies’ reasoning works exactly like this. Zheng’s real accomplishments are spectacular enough to give him a fine place in history… attributing miracles to him does him no honour.

That the Chinese of the Ming era had better knowledge of the world than Europeans of the time, is not in doubt. But most of Menzies’ “reconstruction” of specific, day-by-day comings and goings of Zhengs fleet (which for some reason were not mentioned in the detailed literature of his voyages), with every landfall and discovery conveniently attested by dubious circumstantial evidence, I don’t swallow. Most of the speculative leaps in each chapter depend on one accepting the truth of the speculative leaps made in the previous chapter. The logic runs like this: It’s known that I can jump a distance of three feet. So it’s plausible that I might be able to jump four feet. Accepting the premise that I can jump four feet, wouldn’t it be plausible that I can jump five? And accepting that, wouldn’t be plausible that I can jump six? This continues until I am theoretically jumping twenty feet, or a hundred feet. Menzies’ reasoning works exactly like this. Zheng’s real accomplishments are spectacular enough to give him a fine place in history… attributing miracles to him does him no honour.

One of the things that usually makes me suspicious of speculative works like this is when I find some ordinary error that would not exist if the writer had made serious, systematic inqueries. In this particular case, Menzies claims that he consulted an authority on medieval India who told him that an inscription was in Malayalam, which he claimed to be an “obscure” language, once but no longer spoken on the west coast of India. Now that’s rather odd. There is nothing obscure about Malayalam. Far from being extinct, it is spoken by thirty million people, and is one of India’s official languages. In fact, I know someone who speaks it here in Toronto. There is a corner shop about three blocks from my apartment where DVDs in Malayalam can be rented, and the public library across the street has a shelf full of books in Malayalam. So how did as pathetic an error as that manage to implant itself in a book purporting to have been made from the most careful and exacting research? I’m not saying that this invalidates any of the author’s claims, but it should tip the reader off that any given “fact” in the book might be bullshit.

0 Comments.