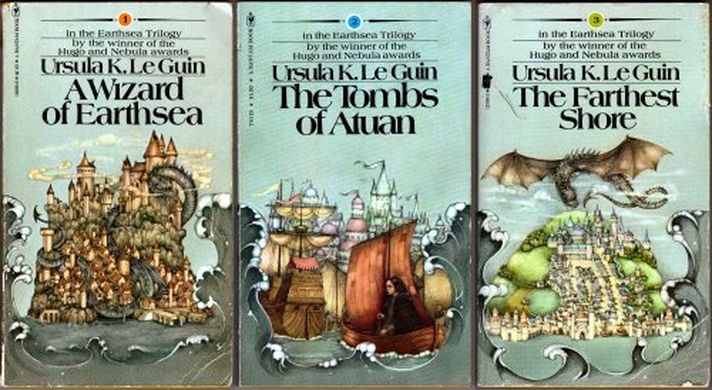

The palace of the Elector of the Palatinate at Mannheim, where its resident orchestra was the heart of the “Mannheim School”.

Haydn and Mozart did not transform baroque music in a vacuum. Change was in the air, and a number of minor composers contributed to it. Among them were the men clustered in the court of the Elector Carl Philipp, at Mannheim. The best musicians from across northern Europe were drawn there in the mid 1700’s. Composers of the Mannheim school introduced a number of novel ideas into orchestral music, such as a more independent role for wind instruments, adding the newly invented clarinet, and much more variable dynamics (the orchestral crescendo is a Mannheim invention). Haydn picked up on these techniques. As a matter of fact, his famous “Paris” symphonies were commissioned for the Mannheim orchestra. I’m listening to a representative selection of Mannheim orchestral music by the Camerata Bern, under the direction of Thomas Füri: Die Mannheimer Schule, a 1980 box set from Archiv. It includes Franz Xaver Richter’s Sinfonia in B‑flat, and his Concerto for Flute and Orchestra in E minor; Johann Stamitz’s Violin Concerto in C, and Orchestral Trio in B‑flat, Op.1; Anton Filtz’s Violin Concerto in G; Ignaz Holzbauer’s Sinfonia Concertante in A and Sinfonia in E‑flat, Op.4; Christian Cannabich’s Sinfonia Concertante in C and Sinfonia in B‑flat; and Ludwig August LeBrun’s Oboe Concerto in D minor. Johann Stamitz, the effective founder of the school, stands out as the most immediately enjoyable in this set. His superb violin concerto merits comparison with Mozart’s. It’s loaded with virtuosity, simplicity, freedom and feeling, characteristics we associate with the next age. Tedious basso continuo and formal ornament are nowhere to be heard in it. I was also charmed by Cannabich and LeBrun’s warm oboe concerto. Other Mannheim composers of note, not represented in this set, were Franz Ignaz Beck, and Johann’s son Carl Stamitz.