This is a fascinating document. Dean Mahomet came from a modestly successful Muslim family in India in the 18th Century, just at the period when the East India Company was absorbing and taking over the crumbling Mughal Empire. At the age of eleven, he became the friend and confidant of a teenage British officer, and for the next sixteen years they advanced together in that curious entity, the Indian Army. Together, they saw action at the siege of Gwalior, the Great Mutiny, and other key events. When a sudden (though apparently undeserved) disgrace ended his friend’s career, D.M. chose to accompany him to his native Ireland. He seems to have been personally charming, and was thoroughly self-educated in the literary culture of England.

This is a fascinating document. Dean Mahomet came from a modestly successful Muslim family in India in the 18th Century, just at the period when the East India Company was absorbing and taking over the crumbling Mughal Empire. At the age of eleven, he became the friend and confidant of a teenage British officer, and for the next sixteen years they advanced together in that curious entity, the Indian Army. Together, they saw action at the siege of Gwalior, the Great Mutiny, and other key events. When a sudden (though apparently undeserved) disgrace ended his friend’s career, D.M. chose to accompany him to his native Ireland. He seems to have been personally charming, and was thoroughly self-educated in the literary culture of England.

In Cork, Ireland, he married into the local Anglo-Irish gentry. He wrote and published his book, which is an account of his military career, with an emphasis on describing the sights and customs of the regions in Northern India that he traversed. It must be remembered that, for him, most places in India were just as “foreign” as Belgium or Denmark would be to an Englishman. The description of a famine is particularly engrossing.

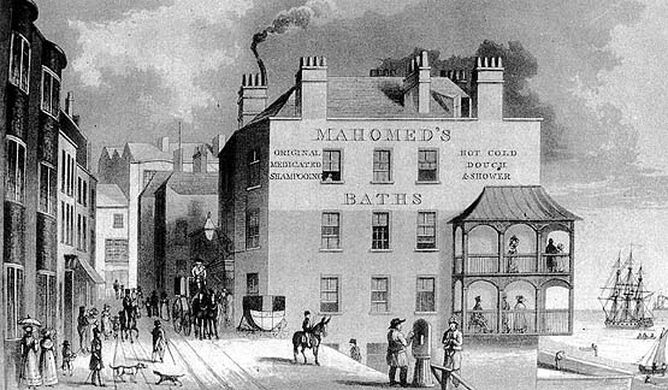

This book is a re-publication of his account, but it does not end there. The most fascinating part of the book is the biographical appendix, following his activities after the publication of the Travels. Dean Mahomet drew on his familiarity with Ayurvedic medicine to establish himself as a masseur and private doctor. Eventually, he moved to London and built a large establishment, a kind of high society bath-house, and became widely known as the “shampooing surgeon”. It appears that he introduced the word “shampoo” into the English language [from Hindi, “champna” = to press], through his second book, a promotional treatise for his techniques.

This book is a re-publication of his account, but it does not end there. The most fascinating part of the book is the biographical appendix, following his activities after the publication of the Travels. Dean Mahomet drew on his familiarity with Ayurvedic medicine to establish himself as a masseur and private doctor. Eventually, he moved to London and built a large establishment, a kind of high society bath-house, and became widely known as the “shampooing surgeon”. It appears that he introduced the word “shampoo” into the English language [from Hindi, “champna” = to press], through his second book, a promotional treatise for his techniques.

The first thing the reader notices in this account is the absence of the kind of ethnic racism that saturated English society in the next century. Dean Mahomet had no trouble attracting and marrying a wealthy European woman, and the issue of his colour or ethnicity does not seem to have been significant. Eighteenth Century Britain was a stew of prejudice, snobbery and injustice, but you get the clear impression that wealth and social class were the language of prejudice at the time. There is no hint that he encountered any obstacles merely for being Asian. Racism, as we are familiar with it in the 19th and 20th centuries, had not yet come into being. There was no cult of racial superiority, but there was a definite cult of class division, and by successfully inserting himself into the class of educated, gentlemanly society, Dean Mohamet was totally separated from the Indian lascars who worked in the docks of London, or the sailors who wandered through British ports.

Another interesting aspect of this book is the glimpse it provides into the East India Company. Contrary to what people are universally taught, the Corporation is not a “free market” entity, and has no connection whatsoever with laissez-faire economics, private property, or free market principles. Its origins lie entirely outside of free market processes and theory. Dean Mahomet’s account provides clear evidence of this.

0 Comments.