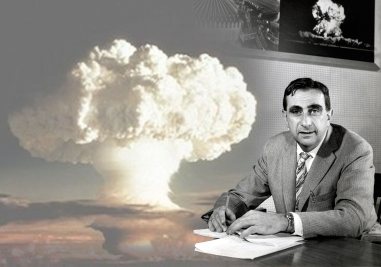

In 1958, the Atomic Energy Commission made a concerted effort to convince the citizens of Alaska to allow them to explode a series of nuclear weapons on the northwestern coast of that state. The effort was directed by Edward Teller, the “father of the hydrogen bomb”, who travelled to Alaska to promote the idea. Teller was a formidable opponent of the nuclear test ban treaty. President Eisenhower, already extremely distrustful of what he was already begining to think of as the “military-industrial complex” and experienced in the real politics of war, was not swayed against the treaty, but he was amenable to Teller’s claims that nuclear weapons could be used for peaceful purposes. The Alaska project was at first dubbed “Ploughshare” and then later changed to “Chariot”.

The project was to use nuclear weapons to excavate a huge harbour in a place where it had no conceivable economic utility, and where it would wreak spectacular destruction of both the ecosystem and the human community. It was promoted to the Alaskans with razzle-dazzle, constantly changing justification, and a landslide of bare-faced lies. Teller himself appears to have been an almost pathelogical liar. Alaskans were told the most fantastic and absurd things imaginable, any concoction of untruths and half-truths that would placate doubts or shut up opposition. Predictably, the local Chamber of Commerce types, the Press, and State legislators jumped on the bandwagon. Here is an example of the kind of thinking displayed by the Anchorage Times: “Asking Alaskans for a decision on this proposed atom experiment is like a doctor asking his patient whether he wants an operation. The easiest answer is ‘no’. The doctor usually tells the patient he must have one for his own good, and the patient does as the doctor says. The atom scientists are the doctor in this case. If they say that adequate safeguards for life and property have been provided, how can laymen say otherwise?” Wow, there’s some rugged individualism and critical journalism for you.

What Teller and his AEC crowd didn’t count on was that Alaska was full of real scientists, some of the most competent in the world. Many were at first enthusiastic for the project. Remember, this was still some time before the growth of a politicized environmental movement, and the biologists, chemists, geologists and naturalists in Alaska assumed that the AEC crowds were working scientists, not ideological crusaders. At varying speeds, however, they were soon disilusioned. The more interaction they had, the more doubts developed, especially as they saw the AEC men demonstrate their ignorance and ride roughshod over scientific method, until eventually the most astute where denouncing AEC men as outright charlatans.

But the real interesting story was among the native Inupiat people of Point Hope, whose land was going to be nuked, and stood the most to lose. It was the Inupiat who overcame and defeated the Juggernaut of State power and mendacity. The story clearly demonstrates why real democracy, and especially local democractic competence and experience, is the best defense people have against these powerful forces.

An Inupiaq family. The photo is undated but I would guess that it dates from five or six years after Project Ploughshare.

Teller and the AEC expected, of course, to be dealing with a handful of primitive people, who could be easily bamboozled and swept aside. When Teller was asked by an economist what would happen to the native people, he answered: “Well, they’ll have to change their way of life… when we have the harbor, we can create coal mines in the Arctic, and they can become coal miners.” This kind of callous, Communist-style arrogance was typical of Teller and his gang.

When the AEC attempted to stage meetings with the native Inupiat, they were surprised and horrified that they were not going to merely give their song and dance and get the kind of naive submission they had gotten from the helpless natives in Eniwotok, in the Marshall Islands. The first thing they discovered was that the Inupiat all had the newly invented portable tape recorders. Most of the high arctic people I’ve known have been chronic “gadgeteers”. Traditional culture empowered them with a fascination for technology, because a proper understanding of tools, and a feeling for technological solutions, is absolutely essential for survival in the extreme north. The tape recorder had been eagerly acquired by the majority of Inuit and related people, as it was practical way to send personal messages back and forth to distant relatives in a land without telephones.

The Inupiat were also far from uninformed or scientifically illiterate. To their frustration, the AEC propagandists discovered that many Inupiat in Point Hope were extremely well read, and easily saw through their illogical and misleading show-and-tell presentations. They found themselves subjected to highly skeptical and incisive questioning. One man in particular, Dan Lisbourne, an Inupiaq whaler and President of the Point Hope Village Council, was “as well-read as any good New-Englander” according to one scientist.

The Point Hope Village council were not political amateurs. The village was the current incarnation of an arctic settlement that had been in continuous existence since before the building of the Pyramids, and in some periods contained more than 600 houses. It was the largest continuously occupied site in the entire arctic, a traditional entrepot of arctic trade, hunting, fishing and whaling. Conversion to the Episcopal Church in the 1890s had been on condition of having self-governing councils in all church affairs. The modern village governing council had been around since 1920, and its self-made constitution had been formally recognized by the U.S. Government since 1940.

I will leave to the reader to discover the inspiring, and sometimes amusing tactics which the Inupiat employed to prevent the AEC from destroying their homes and lives. When it became obvious that Alaska’s press was not doing its job, they founded the first State-wide native newspaper, the Tundra Times. Point Hope needed allies, and Inupiaq council organized larger and larger political efforts until most of naive Alaska was involved and onside, formed coherent alliances with responsible scientists, and built publicity networks that reached into mainstream America. The disastrous project was eventually shelved.

All of this demonstrates why democratic techniques are so crucially important for the defense of ordinary people against the power of the mighty.

0 Comments.