In Snefflls Iokulis kraterem kem delibat umbra Skartaris Iulii intra kalendas deskende, audas uiator, te terrestre kentrum attinges. Kod feki. Arne Saknussemm.

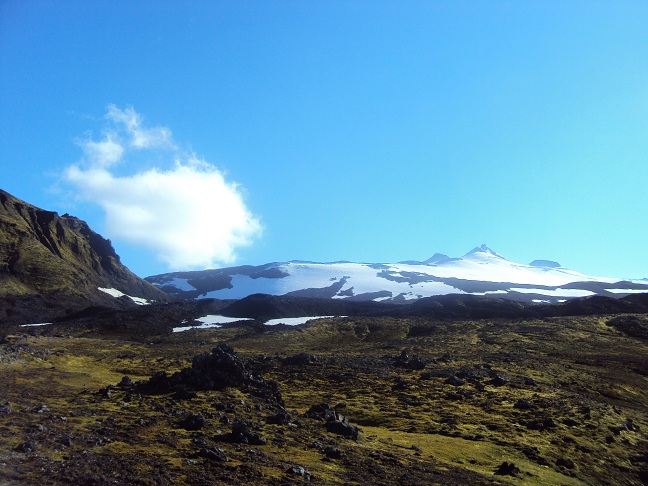

Away from computers for awhile, as I’ve spent some time out in Iceland’s spectacular landscape. The interior of the island is virtually uninhabited, but even the coastal areas are largely mountains bare of trees, roads, buildings and people. The mountainsides are extraordinarily steep, and often unclimbable as they consist of loose pebbles on which you can get little foothold. You look for patches of green, which usually mean the slope is gentle enough for the mosses and grasses to take hold. Most of the mountains are slabs created by ancient lava flows, and they are broken into cliffs of astonishing sharpness. Mixed in with these are volcanic cinder-cones. It is possible to walk enormous distances, with an unimpeded view of many miles, and not see a single person. But you always run across sheep, and, in lower areas, untended horses. Walking over long stretches of this landscape requires a willingness to accept sudden and unpleasant changes of weather. It may be warm and sunny, but an icy wind may pick up at any time, or rain clouds roll in within minutes.

It was my ambition, since the first planning of this trip, to climb Snæfellsjökull. I have now fulfilled this ambition, though it took a lot out of me. I’m not so physically well-suited for this sort of thing, anymore.

I started from the ocean shore, just east of the fishing port of Ólafsvík. The blue North Atlantic lapped rhythmically on the beach. The path towards the extinct volcano was guarded by a defiant ram, who seemed to object to me turning up the gravel road, and was not in the least afraid of me. About twenty km of walking would bring me to the glacier — not a great distance, but it would be all uphill. The road, of which the ram was so possessive, was not much more than gravelly car track even at its beginning, and it would deteriorate significantly after a short distance. My plan was to take it as far as I could, then switch to open terrain when I had to.

Snæfells [Snæfellsjökull properly refers to the glacier on top of it] is possibly the first mountain I knew by name, unless you count the miniscule Kamiskotia ‘mountains’ of the Porcupine region of Northern Ontario, which rise no higher than a few hundred feet. Snæfells rises 1833 meters from sea level, making it one of Iceland’s taller mountains. In Jules Verne´s Voyage au centre de la terre (1864), the stalwart Victorian-era heroes are led by a mysterious cypher (quoted above) to the crater of Snæfells, from which they descend deep into the interior of the earth (not to its exact center, as the English translation of the title suggests). Snæfellsjökull is also the locale of one of the silliest of the Icelandic sagas, the Bárðar saga Snæfellsáss, which should be read by those who interpret the sagas as realistic novels or reliable chronicles. It has a smorgasbord of miracles, giants, trolls, and absurdities. But I wasn’t seeking trolls and giants, and didn’t expect to find any route to the interior of the earth — I was more interested in the center of myself. I usually undertake such ventures into the wild in order to think through personal problems, and I have some weighty ones to deal with, of late.

The going was tough, even on the road. The grade was steep, with no relieving horizontal stretches. Broken up lava, pumice and ash are not a kind surface. But the landscape was breath-taking. It was not long before I could look at the sea, far bellow, and at fishing trawlers bobbing in the Atlantic. With no forest, the mountains were a confusing jumble of abstract shapes, and it was impossible to tell what was near and far, what was big and small. This problem of judging distances got more serious when I left the road. I had to rely on guesswork to guide me in climbing steep slopes of sharp pebbles, navigating around thousands of boulders, and great fields of a spongy lichen which is familiar to me from the Canadian arctic. My main fear was that I would miscalculate time, and find myself at too high an altitude at nightfall. Fortunately, the days are very long in Iceland’s September.

The slow progress, usually requiring only routine attention, allowed me plenty of time to think. This is the kind of place I go to for serious thinking, probably because they underline the solitude that is the recurring theme of my life. I’ve lived most of my life alone — far more alone than most people ever experience. It has not been my choice, merely the way the cards have been dealt. This is why solitary journeys through forests, deserts, and wastelands figure prominently in both my fiction writing and in my real life.

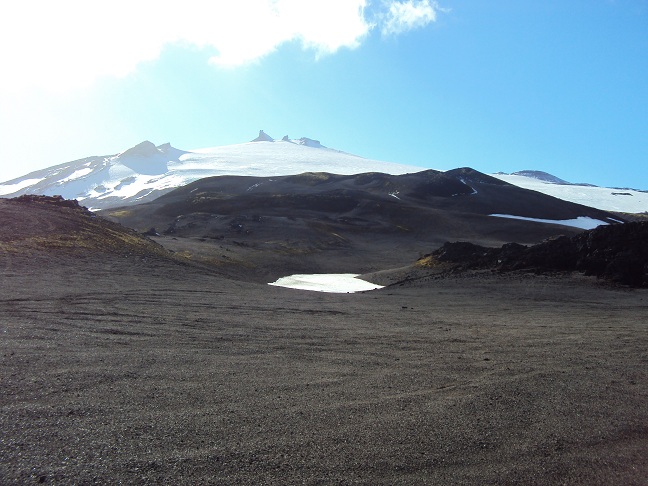

When I crossed a fresh snowfall and came over a crest, the summit of Snæfells came into view. The summit is a black spike of rock sticking up like a finger through the glacier. This is an entirely new phenomenon: throughout the thousand years of history that humans have known Snæfells, the actual black, rocky peak has never been seen until this year, when the dramatic shrivelling of the glacier revealed it.

Just before I left for this trip, I had some very discouraging news. For three months, now, my left should has been extremely painful, and my left arm is restricted in its mobility. The pain varies in intensity, but it is always there, and often it is strong enough to prevent me from sleeping. Any twisting of the arm, or abrupt motion can be extremely painful. It has acted as an irritant, making my temper sour. Over the last month, I’ve wasted a good deal of time taking cardiac tests, which medical protocol insists must be done first, though I was certain the problem was mechanical or neurological. A few days before I left, it was made clear that the probable cause is a muscle that has been frayed and damaged in my shoulder, a side effect of the work I do delivering dental material for a laboratory. I walked around every day with a bag of reasonably heavy material slung on that shoulder, and the repetition, rather than the weight itself, has done the damage. I am not a salaried employee, but a contract worker without benefits. When the pain started, I switched the shoulder I use. However, it is likely that this will do the same thing to the other shoulder, in time. So I can’t pursue that kind of work much longer.

I had counted on the delivery job to keep my rent and expenses paid while I write two books — one a synthesis of my academic work in history and social issues, the other a second novel. The first novel never found a publisher, but I still believe that what I have to say is best said in fictional form. However, I have been more successful in writing non-fiction, and my small reputation is making it plausible that I can put together a publishable book. The physical demands of the delivery job have always taken a lot out of me, and progress in both of these books has been slow. But I’ve not had to worry about paying the rent, and I live comfortably in a little apartment. Some shoestring adventures, such as this one to Iceland, have kept me sane. They cut into my security, but without them I would live so hopelessly as to make the effort futile.

Now, it seems, I cannot maintain the delivery job too much longer without turning myself into a cripple. I am confronted with a much greater urgency to get my intellectual work done. Over the next year, I must establish myself as a successful professional. This is not the age of Darwin, when an amateur country parson could shake the world with his thoughts. I have never been anything more than an upstart amateur, and that has to change. So, over the next year, I will be under great pressure to accomplish some very difficult goals. I will have to sharpen my concentration, increase my workload, and eliminate side-tracks.

The critical factor in this is morale, which has always been my Achilles’ heal. I long ago resigned myself to the fact that I would never have any of the things in life that most people take for granted as their due, and I would never get from people any of the normal forms of respect. It is not the kind of life I would have chosen for myself, and I would not wish it on anyone else, but it is what I’m stuck with. It makes for a wearying, cold way of life, punctuated by bouts of despair. But I can no longer afford to tolerate some aspects of it. To survive, I will have to concentrate on the few people who show at least some signs of warmth and affection, and those who at least respect my work. The work I’ve done over my lifetime has been hard and flinty stuff, driven by a desire to learn truths, and I think it deserves some respect. So anyone who has neither respect for my work, nor warmth and affection to offer, I must remove from my attention. I can no longer afford to do anything else.

When the peak of Snæfells hove into view, the lush musical score that Bernard Hermann composed for the 1959 film of Journey to the Center of the Earth popped into my head. It stayed there, playing in snatches as I made my way to the glacier. The glacier has been retreating quickly, and has left barren, scraped alley-ways that betray its former presence as vividly as a skeleton betrays the former presence of a human. When I reached the ice, it did not take much travel on its surface to see that it was too dangerous to proceed. Above me were crevices and stress lines in the ice showing just how rotten the underlying ice sheet must be. I would be a fool to climb much higher. But I had walked upon the glacier, and I had seen what I most wanted to see.

By the time I made it back down to the sea, my hiking shoes had been torn to shreds. Now they are held together with electrical tape. I had dressed well, but I had still caught a chill. By the time I got to the village of Stykkishólmur, I had a raging head cold. This has persisted, but I am soothed by the amniotic pleasure of geothermal bath. These marvellous things abound in Iceland. Now that I know them, I’m heartbroken that I can’t have them back home (unless I move to British Columbia).

0 Comments.