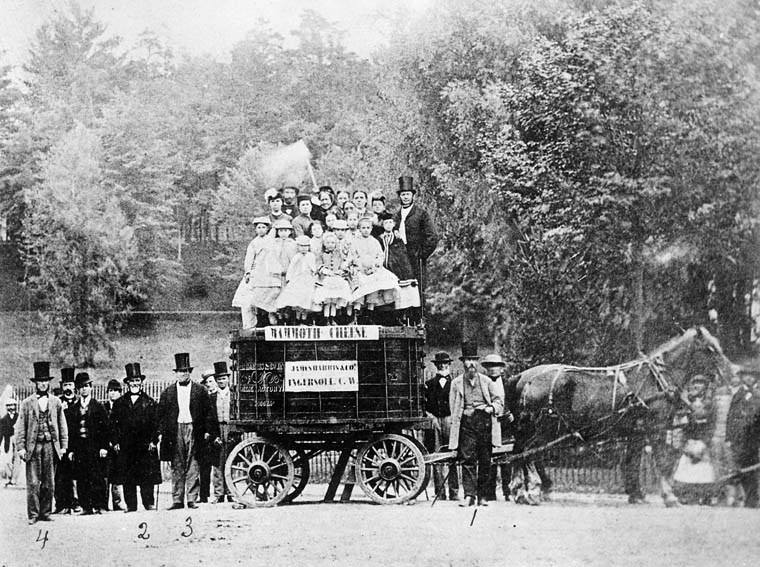

The original 7,300 lb Mammoth Cheese of 1866, departing its birthplace in Ingersoll, Ontario.

I’m doing a little research on Canadian literature of the 19th century. This is not a field that overwhelms the researcher with an abundance of masterpieces. Canada, at this time, was an empty, rugged, pioneering place, vaguely British in the society of its small urban elite, but for most people culturally closer the the western parts of the United States. Montreal had a modest literary life in French, drawing on several centuries of folklore and even producing a few operas. These works were unknown in the rest of the French-speaking world. English-speaking Montrealers were more interested in commerce than culture. Outside of Montreal, the only real city, there was not much other than small towns, farms and wilderness.

But in the Victorian Age, Canadian farmers and lumberjacks read quite a bit. Many years ago, I worked as a farm hand in rural Ontario. I often made deals with elderly farm couples to take in hay, or tend livestock, in exchange for the collections of old books that their parents and grandparents had hidden away in basements and barns. Most had been gathering dust (or hay twigs) for as much as a century. In this way, I built up an impressive collection of nineteenth century books, including a beautiful complete set of Walter Scott, and I also got a good impression of what ordinary Canadians actually read. There were, of course, numerous books of sermons and exhortations to religious piety, and popular magazines. Some of these, like The Strand, and Lippincott’s Monthly, had very high standards of content and style. Farmers were much involved in national politics and the urgent reforms of the day. But they also read more literary stuff. The same books turned up over and over again. These were the Sacred Texts, the four cornerstones of Canadian Culture of the time: the poems of Robert Burns, the novels of Walter Scott and Charles Dickens, and the plays of Shakespeare. The first two testify to the overwhelming influence of Scottish culture in Canada, at the time. The Americans Longfellow, Emerson and Mark Twain were popular, but they did not have the same exalted status. Among more contemporary English writers there were Tennyson, Browning, and the now forgotten, but at the time immensely respected Edwin Arnold, who wrote a book-length life of the Buddha in verse, and who was inordinately fond of exclamation points. Dour Canadian pioneers were strangely familiar with lines such as:

Ah! Blessed Lord! Oh, high deliverer!

Forgive this feeble script, which doth thee wrong,

Measuring with little wit thy lofty love.

Ah! Lover! Brother! Guide! Lamp of the Law!

I take my refuge in Thy name and Thee!

I take my refuge in Thy law of good!

I take my refuge in Thy order! OM!

The dew is on the lotus! — Rise, Great Sun!

And lift my leaf and mix me with the wave.

Om mani padme hum, the sunrise comes!

The dewdrop slips into the shining sea!

It is hard, however, to imagine that the doctrines of Samsara, Karma and Madhyama-pratipad exercised much influence on the flinty Presbyterians and Methodists of Ontario farm country, no matter how many exclamation points were hurled at them.

For teenagers, the adventure novels of G. A. Henty and R. M. Ballantyne (who spent his youth in Canada, and set much of his fiction here), were ubiquitous.

The only Canadian-born novelist read internationally in the mid-19th century was John Richardson (Wacousta [1832] & The Canadian Brothers [1840]). In Victorian era Canada, even the humblest citizens were not only expected to read poetry, but to write it. Some even managed to find readers outside the country. Pre-eminent among them was Pauline Johnson [Tekahionwake], the Mohawk poet whose celebrations of Native Canadian culture in verse reached an international audience. It is interesting that the two internationally known writers in Canada were both of Native Canadian origin (Richardson was an Odawa). Richardson’s work has faded into obscurity, but Johnson is still read, and her poems have considerable charm.

But outside of these modest literary achievements, there was a deluge of terrible verse, ground out by local eccentrics in small towns across the land. Of these, few can have reached the Olympian heights of horribleness achieved by James McIntyre of Ingersoll, Ontario. McIntyre wrote mostly about cheese, a subject which he contemplated with the same enthusiasm that Bunyan contemplated salvation and Wordsworth contemplated the infinite. Cheese was the center of McIntyre’s epistemology, eschatology, and metaphysics. One poem, The Oxford Ode to Cheese, reads:

The ancient poets ne’er did dream

That Canada was land of cream,

They ne’er imagined it could flow

In this cold land of ice and snow,

Where everything did solid freeze

They ne’er hoped or looked for cheese.

And since they justly treat the soil,

Are well rewarded for their toil,

The land enriched by goodly cows,

Yie’ds plenty now to fill their mows,

Both wheat and barley, oats and peas

But still their greatest boast is cheese.

But his masterpiece was undoubtedly Ode on the Mammoth Cheese Weighing over 7,000 Pounds (1866), which I must quote in its entirety:

We have seen thee, queen of cheese,

Lying quietly at your ease,

Gently fanned by evening breeze,

Thy fair form no flies dare seize.

All gaily dressed soon you’ll go

To the great Provincial Show,

To be admired by many a beau

In the city of Toronto.

Cows numerous as a swarm of bees,

Or as the leaves upon the trees,

It did require to make thee please,

And stand unrivalled, queen of cheese.

May you not receive a scar as

We have heard that Mr. Harris

Intends to send you off as far as

The great World’s show at Paris.

Of the youth beware of these,

For some of them might rudely squeeze

And bite your cheek, then songs or glees

We could not sing, oh! queen of cheese.

We’rt thou suspended from balloon,

You’d cast a shade even at noon,

Folks would think it was the moon

About to fall and crush them soon.

What can one say? McIntyre was apparently a very nice man, beloved in his community, and sincere in his dedication to the muse. In poem after poem, he celebrated the delights of turophilia, and pride in the agricultural achievements of Ontario. If you have ever sampled some of the better country cheeses of this province, such as Harrowsmith or Balderson’s, you might be tempted to place them on the same plane as salvation or the infinite. In fact, I would dare to place them on a higher plane. I don’t really have a handle on the infinite, and I don’t believe in salvation beyond the grave, but I can appreciate a good cheese.

0 Comments.