I have two versions of this well known medieval piece, which is important both from a literary and a musical point of view. European drama evolved, in the Middle Ages, from the liturgy of the Church. What began as the modest elaborations on the ceremony of the mass eventually led, by slow increments of change, to Hamlet. Similarly, the simple monophonic chant of the mass was the acorn from which opera, symphony and concerto grew. In both aspects, it was the necessity to entertain the audience, rather than God, that pushed the process.

I have two versions of this well known medieval piece, which is important both from a literary and a musical point of view. European drama evolved, in the Middle Ages, from the liturgy of the Church. What began as the modest elaborations on the ceremony of the mass eventually led, by slow increments of change, to Hamlet. Similarly, the simple monophonic chant of the mass was the acorn from which opera, symphony and concerto grew. In both aspects, it was the necessity to entertain the audience, rather than God, that pushed the process.

The Ludus Danielis comes to us through a 13th Century manuscript in the Cathedral of Beauvais, but it appears to have been written a century earlier. It is clearly ascribed to a group of students of that Cathedral. The text is, of course, in Latin. It includes dialogue and some fairly explicit stage directions. The musical notation is only for the vocal parts, though an orchestral accompaniment is implied. The notation gives melody, but not tempo or meter, so there is a great deal of room for interpretation in the music. We also know that Medieval ideas of meter were closer in spirit to modern jazz than to the rigid timing of classical music.

Given this broad scope for interpretation, it’s not surprising that the two versions of the Ludus Danielis in my collection sound nothing like each other. The first, performed by the Schola Hungarica in the early 1980s, leans as far toward the liturgical as possible. The only accompaniment is some simple percussion. The singing style is lean, and the whole effect is “churchy”, though the solo passages are treated quite beautifully as arias. It was recorded in a 12th Century Hungarian Church. The other performance is the pioneering 1955 performance in the Cloisters of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, by New York Pro Musica. This was probably the first performance of the piece since the Middle Ages, and it was done with great enthusiasm and care. W. H. Auden even wrote a long poem as a preamble to the performance. It leans far more towards the drama. The orchestration is full, including trumpets, rebec, portative organ, psaltery, recorders, viele, harp, various percussion, and even highland bagpipes. Everything is done to stress the play-like aspects. The contrast between the two is so strong that only remembering key melodies would let you know that you were listening to the “same” piece. The whole feeling is different. One seems a sacred contemplation, the other a boisterous popular entertainment.

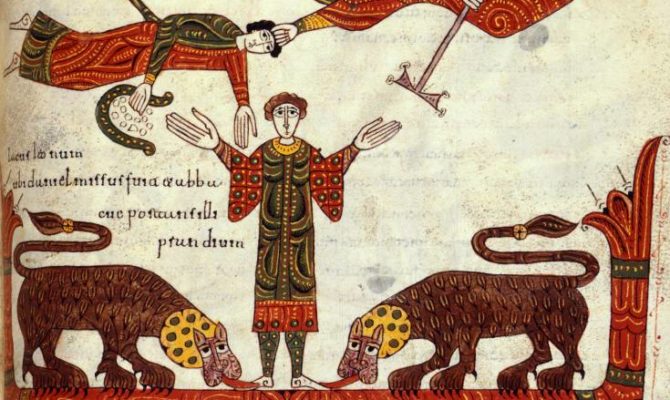

Personally, I suspect that the Pro Musica version is closer to what was performed in the Middle Ages. The Schola Hungarica is seeking a purity and simplicity that is extremely beautiful, but unlikely to have been what a bunch of medieval students would have liked, or produced. I’m as much interested in the play’s literary element as in the music, and it seems to me that the lurid subject of Daniel and Belshazzar, the writing on the Wall (“Mene, mene, tekel upharsin!”), and clearly described action scenes of people being devoured by lions, is hardly material design for contemplative meditation.

0 Comments.