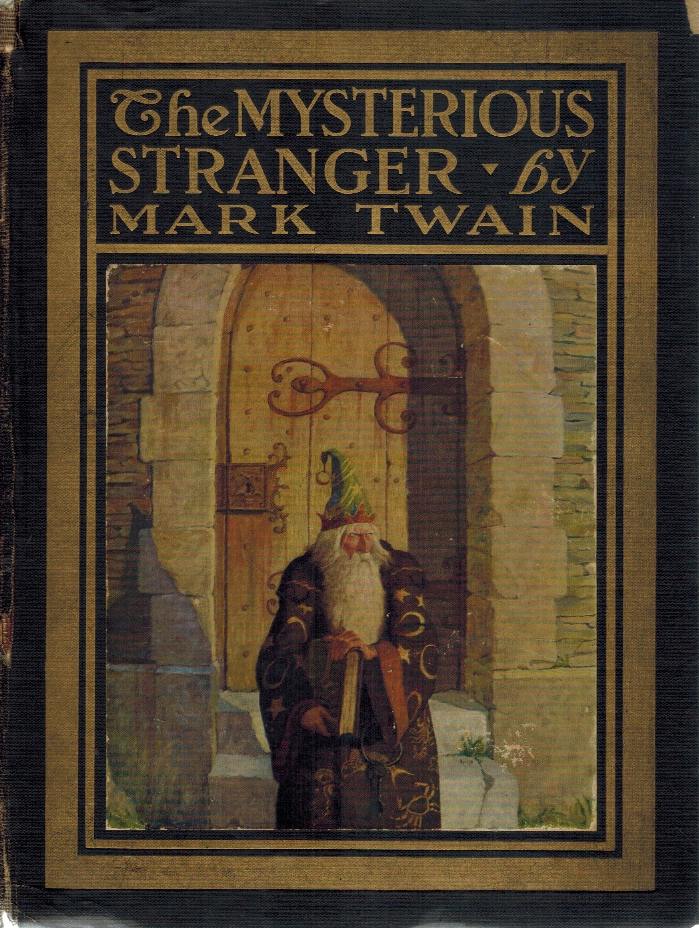

Some famous books are obvious masterpieces, most have a mixture of merits and flaws, but a few are just plain weird. In the last category, few would hesitate to place Mark Twain’s Mysterious Stranger. Even attempting to find and read a copy can be a confusing task. Twain’s last novel existed in a number of fragmentary, unfinished versions, written in between 1897 and 1908. None were published in his lifetime. His literary executor, Albert Bigelow Paine, and Frederick Duneka, an editor at Harper & Brothers, cobbled together a version and published it in 1916. This is the version that became known to the public. I have just reread this 1916 version in its original edition, The Mysterious Stranger — A Romance by Mark Twain with Illustrations by N.C.Wyeth [shown at left]. Wyeth’s illustrations add greatly to the pleasure. He was one of the greatest of book illustrators in a period that boasted Kay Nielson, Howard Pyle, Akseli Gallen-Kallela, Edmund Dulac and Arthur Rackham. However, this edition took extraordinary liberties with Twain’s work, a fact which was not made plain until 1963, when John S. Tucker published Mark Twain and Little Satan: The Writing of The Mysterious Stranger. Twain had first attempted the story in 1897, leaving an untitled fragment [now called the St. Petersburg Fragment]. Between 1897 and 1900, Twain produced a more substantial manuscript which he called The Chronicle of Young Satan. In 1898, he produced a short and much very different text which he called Schoolhouse Hill, incorporating elements from the first two. Finally, between 1902 and 1908, Twain produced an almost complete version which he titled No. 44, the Mysterious Stranger: Being an Ancient Tale Found in a Jug and Freely Translated from the Jug. Tucker’s scholarship revealed that Paine and Duneka had relied primarily on the earlier Chronicle of Young Satan, had removed substantial portions, changed names, characters, added bits written by themselves, and pasted the last chapter of Twain’s final version onto the pastiche. None of these extreme alterations was acknowledged, an act of literary vandalism and fraud that went uncorrected until the University of California Press published three of the original manuscripts in 1969. No.44, the Mysterious Stranger, Twain’s final version, did not see popular publication until 1982, and I have finally read this authoritative text.

Some famous books are obvious masterpieces, most have a mixture of merits and flaws, but a few are just plain weird. In the last category, few would hesitate to place Mark Twain’s Mysterious Stranger. Even attempting to find and read a copy can be a confusing task. Twain’s last novel existed in a number of fragmentary, unfinished versions, written in between 1897 and 1908. None were published in his lifetime. His literary executor, Albert Bigelow Paine, and Frederick Duneka, an editor at Harper & Brothers, cobbled together a version and published it in 1916. This is the version that became known to the public. I have just reread this 1916 version in its original edition, The Mysterious Stranger — A Romance by Mark Twain with Illustrations by N.C.Wyeth [shown at left]. Wyeth’s illustrations add greatly to the pleasure. He was one of the greatest of book illustrators in a period that boasted Kay Nielson, Howard Pyle, Akseli Gallen-Kallela, Edmund Dulac and Arthur Rackham. However, this edition took extraordinary liberties with Twain’s work, a fact which was not made plain until 1963, when John S. Tucker published Mark Twain and Little Satan: The Writing of The Mysterious Stranger. Twain had first attempted the story in 1897, leaving an untitled fragment [now called the St. Petersburg Fragment]. Between 1897 and 1900, Twain produced a more substantial manuscript which he called The Chronicle of Young Satan. In 1898, he produced a short and much very different text which he called Schoolhouse Hill, incorporating elements from the first two. Finally, between 1902 and 1908, Twain produced an almost complete version which he titled No. 44, the Mysterious Stranger: Being an Ancient Tale Found in a Jug and Freely Translated from the Jug. Tucker’s scholarship revealed that Paine and Duneka had relied primarily on the earlier Chronicle of Young Satan, had removed substantial portions, changed names, characters, added bits written by themselves, and pasted the last chapter of Twain’s final version onto the pastiche. None of these extreme alterations was acknowledged, an act of literary vandalism and fraud that went uncorrected until the University of California Press published three of the original manuscripts in 1969. No.44, the Mysterious Stranger, Twain’s final version, did not see popular publication until 1982, and I have finally read this authoritative text.

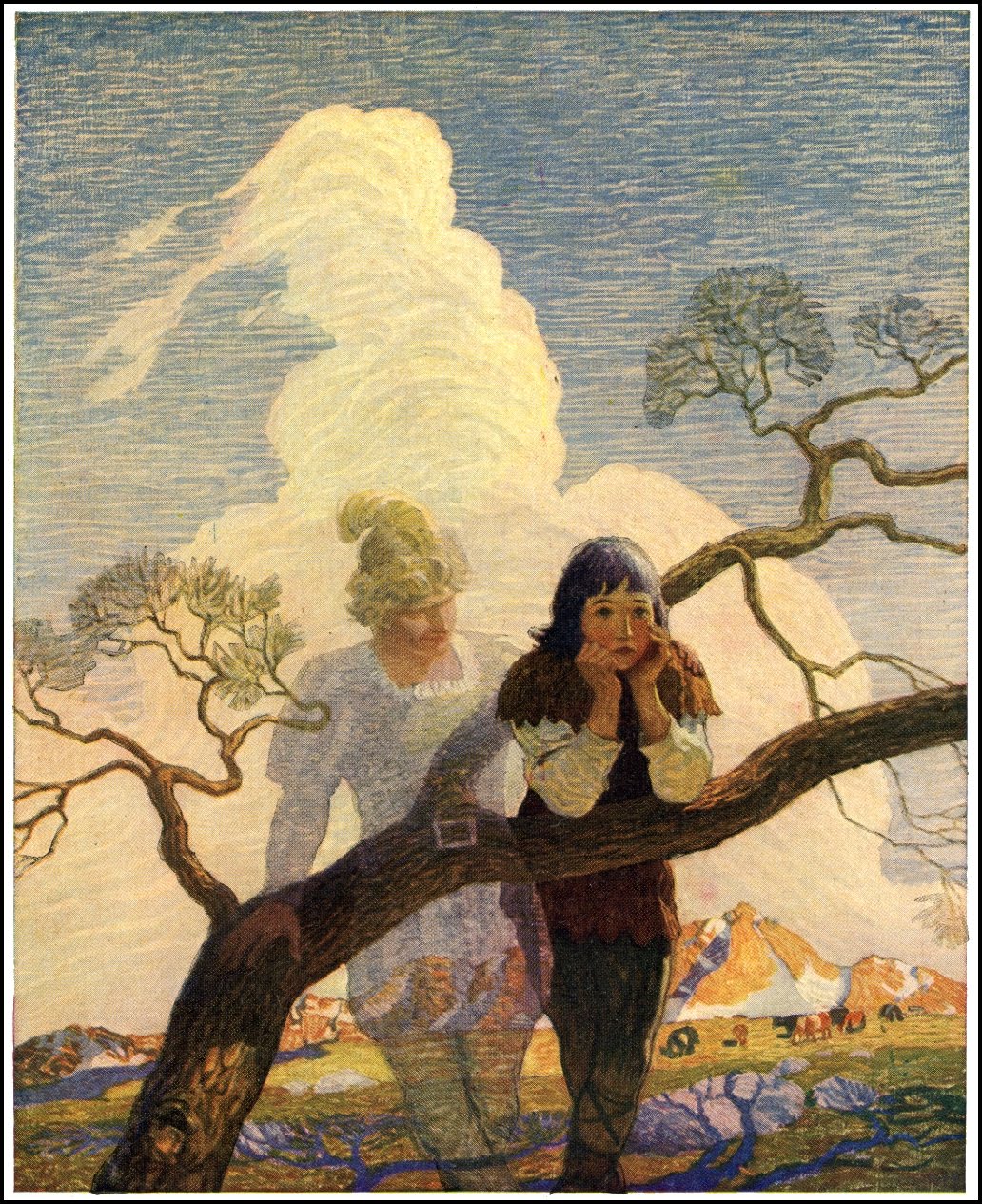

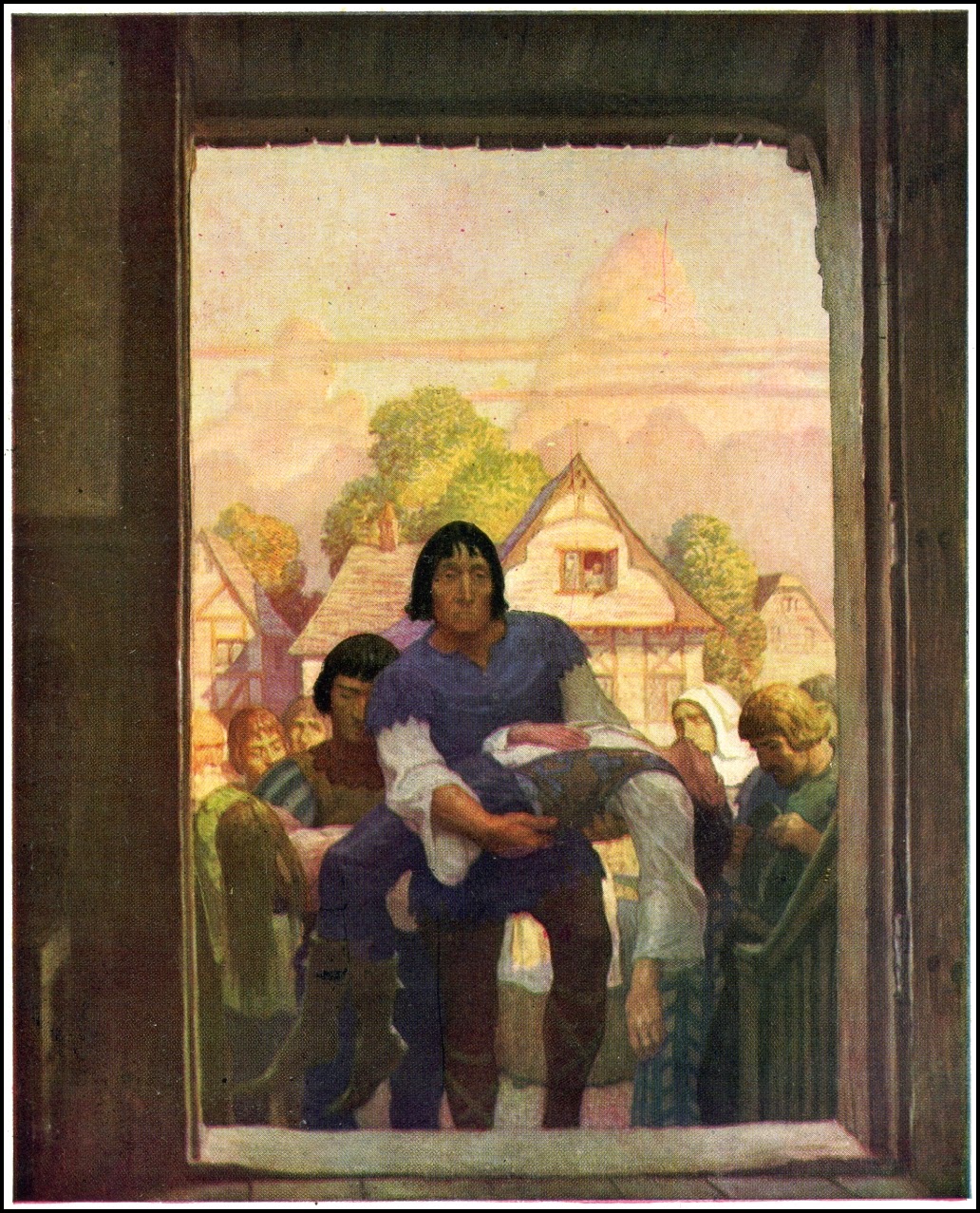

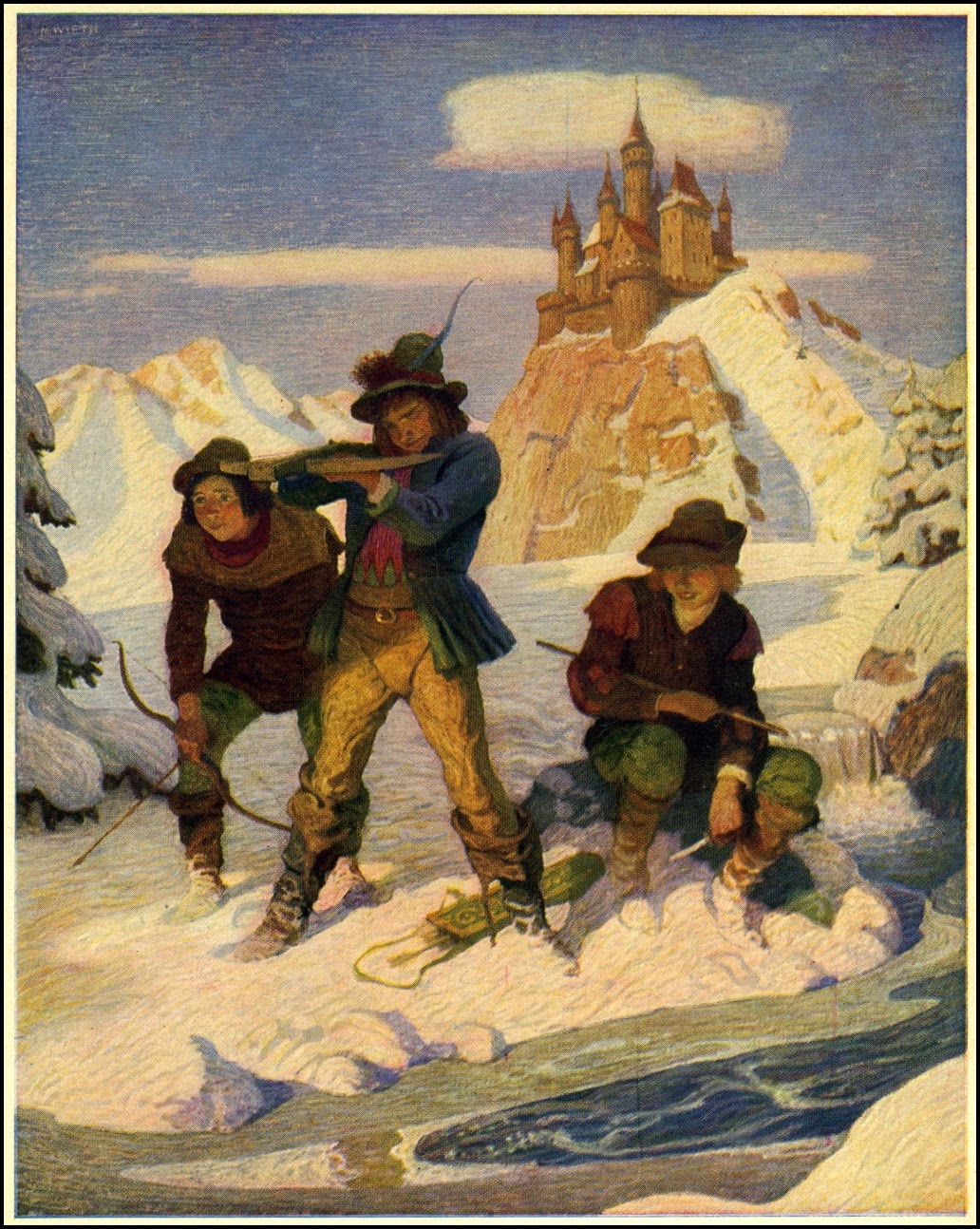

It reveals a work even more peculiar than the 1916 version. The story is set in the year 1490, in a fictional Austrian village. The narrator is a sixteen-year-old village boy named August Feldner, an apprentice in a print-shop. Twain, who was himself a printer’s apprentice in Hannibal, Missouri when he was a boy, fills the narrative with the arcana of the printing trade. The print shop’s master is a sympathetic character, but there are several villains: the master’s shrewish and scheming wife, a fraudulent magician-alchemist, and a persecuting priest. The apprentices, among whom August counts for little, are a mixed bag of characters, but all are obsessed with the perquisites and pecking order of the trade. Twain takes every occasion to demonstrate the superstitious and credulous mentality of the time, using his well-honed satirical style. But he also evokes the innocence of childhood and the humble pleasures or village life. Twain began writing this version while he was staying in a small Swiss village, which he likened to Hannibal in his diary. Into this fictional community there suddenly arrives a mysterious stranger, a boy apparently of August’s age, bedraggled, seeking food and shelter, for which he offers to work. When asked his name, he gives it as “Number 44, New Series 864,962.” Twain dwells on the boy’s bewitching beauty. Befriending August, and taking him into his confidence, he reveals himself as an “angel”, in fact a relative of Satan himself (Satan, of course, being the rebel angel), and existing outside of space and time. He communicates telephathically with August, teaches him how to make himself invisible, brings him articles from the future, and whisks him to mountain tops and China in an instant. They travel to the past. He also shows August humanity’s horrors, including the burning alive of a “witch”, the tragic lives of the poor, and the grim results of alternate time-lines of history. He seems utterly oblivious to August’s notions of propriety, piety, and ethics. When No.44’s diligence earns him a position as apprentice, the other apprentices go on strike in resentment, sabotaging an urgent printing job. No.44 conjures up an army of dopplegangers who do the work, and there is a comic battle in which each character fights his own duplicate. Finally, No.44 is burnt as a witch, only to reappear to August and explain to him that:

It reveals a work even more peculiar than the 1916 version. The story is set in the year 1490, in a fictional Austrian village. The narrator is a sixteen-year-old village boy named August Feldner, an apprentice in a print-shop. Twain, who was himself a printer’s apprentice in Hannibal, Missouri when he was a boy, fills the narrative with the arcana of the printing trade. The print shop’s master is a sympathetic character, but there are several villains: the master’s shrewish and scheming wife, a fraudulent magician-alchemist, and a persecuting priest. The apprentices, among whom August counts for little, are a mixed bag of characters, but all are obsessed with the perquisites and pecking order of the trade. Twain takes every occasion to demonstrate the superstitious and credulous mentality of the time, using his well-honed satirical style. But he also evokes the innocence of childhood and the humble pleasures or village life. Twain began writing this version while he was staying in a small Swiss village, which he likened to Hannibal in his diary. Into this fictional community there suddenly arrives a mysterious stranger, a boy apparently of August’s age, bedraggled, seeking food and shelter, for which he offers to work. When asked his name, he gives it as “Number 44, New Series 864,962.” Twain dwells on the boy’s bewitching beauty. Befriending August, and taking him into his confidence, he reveals himself as an “angel”, in fact a relative of Satan himself (Satan, of course, being the rebel angel), and existing outside of space and time. He communicates telephathically with August, teaches him how to make himself invisible, brings him articles from the future, and whisks him to mountain tops and China in an instant. They travel to the past. He also shows August humanity’s horrors, including the burning alive of a “witch”, the tragic lives of the poor, and the grim results of alternate time-lines of history. He seems utterly oblivious to August’s notions of propriety, piety, and ethics. When No.44’s diligence earns him a position as apprentice, the other apprentices go on strike in resentment, sabotaging an urgent printing job. No.44 conjures up an army of dopplegangers who do the work, and there is a comic battle in which each character fights his own duplicate. Finally, No.44 is burnt as a witch, only to reappear to August and explain to him that:

“Nothing exists; all is a dream. God — man — the world, — the sun, the moon, the wilderness of stars: a dream, all a dream, they have no existence. Nothing exists save empty space — and you!”… “And you are not you — you have no body, no blood, no bones, you are but a thought. I myself have no existence, I am but a dream — your dream, creature of your imagination. In a moment you will have realized this, then you will banish me from your visions and I shall dissolve into the nothingness out of which you made me….”

He explains that human ideas are self-evidently absurd, such as a belief in “a God who could make good children as easily as bad, yet preferred to make bad ones; who could have made every one of them happy, yet never made a single happy one; who made them prize their bitter life, yet stingily cut it short; who gave his angels painless lives, yet cursed his other children with biting miseries and maladies of mind and body; who mouths justice, and invented hell; who mouths morals to other people, and has none himself; who frowns upon crimes, yet commits them all; who creates man without invitation, then tries to shuffle the responsibility for man’s acts upon man, instead of honorably placing it where it belongs, upon himself; and finally, with altogether divine obtuseness, invites this poor abused slave to worship him!…”

It’s no wonder that Twain considered the book unpublishable. And it’s not surprising that it was written in the shadow of tragedy. Of the three daughters that Twain doted on, one died of meningitis in 1896, at the age of twenty-four, another drowned in a bathtub in 1909. Earlier, his only son had died of diptheria when but a toddler. Olivia, his wife of thirty-four years, to whom he was utterly devoted, died after a protracted illness while they were in Italy. Twain had plenty of reason to be bitter. This strange novel embodies, in one way or another, all of his life-long obsessions, from his fascination with childhood, and with the Middle Ages, to his paring of dual characters, one “normal” and the other a kind of pagan spirit — Tom and Huck mutated into August and #44. His hatred of injustice and religious hypocrisy are in there in spades. But most of all, the novel dwells on the puzzle of suffering and the multi-faceted nature of consciousness. All Twain’s doubts and torments are resolved in a bizarre kind of metaphysical solipsism. I don’t think, however, that this should be taken as a declaration of Twain’s actual belief. Twain was a Menippean writer, given to playing out contradictory schemata of the world in the form of satires, melodramas and burlesques. But there is no doubt about his using this instrument to deal with personal anguish.

It’s no wonder that Twain considered the book unpublishable. And it’s not surprising that it was written in the shadow of tragedy. Of the three daughters that Twain doted on, one died of meningitis in 1896, at the age of twenty-four, another drowned in a bathtub in 1909. Earlier, his only son had died of diptheria when but a toddler. Olivia, his wife of thirty-four years, to whom he was utterly devoted, died after a protracted illness while they were in Italy. Twain had plenty of reason to be bitter. This strange novel embodies, in one way or another, all of his life-long obsessions, from his fascination with childhood, and with the Middle Ages, to his paring of dual characters, one “normal” and the other a kind of pagan spirit — Tom and Huck mutated into August and #44. His hatred of injustice and religious hypocrisy are in there in spades. But most of all, the novel dwells on the puzzle of suffering and the multi-faceted nature of consciousness. All Twain’s doubts and torments are resolved in a bizarre kind of metaphysical solipsism. I don’t think, however, that this should be taken as a declaration of Twain’s actual belief. Twain was a Menippean writer, given to playing out contradictory schemata of the world in the form of satires, melodramas and burlesques. But there is no doubt about his using this instrument to deal with personal anguish.

In the same year that the recovered text reached general publication, a small film production company made a reasonably faithful cinematic version of the story. This is one of the oddest “family films” (for it was marketed as such) ever made. No.44’s final speech, blasphemous by any Christian standards, is in the film, which would nowadays make it non grata in the U.S., even though it probably voices the disenchantment of many modern Americans. It was filmed in Austria. Production values were low-end, but adequate. August was played by Chris Makepeace, a Canadian child actor who had briefly been successful in the comedy Meatballs. No.44 was played by Lance Kerwin, a hard-working juvenile television actor. The casting was perfect. Makepeace’s naïve persona and Kerwin’s mischievous one fit the story well. Ironically, Kerwin later became a drug addict, then found religion.

—

26166. [2] (Mark Twain) The Mysterious Stranger [ill. N.C. Wyeth] [1916 Harper Edition]

[not same as Eseldorf version [Diary of Young Satan] at 22281 or No.44 version]

26167. (Mark Twain) No.44, the Mysterious Stranger [Mark Twain Project text]

26173. (Joseph Csicsila) John S. Tuckey’s Mark Twain and Little Satan [article]

26174. (John Sutton Tuckey) Mark Twain and Little Satan: The Writing of The Mysterious Stranger

0 Comments.