Iceland, considering its small population (329,100 at last count), has produced a phenomenal amount of rock music that has reached a global audience. It’s as if Oshawa, Ontario or Eugene, Oregon each had a half-dozen world-level bands. Absurdly improbable, when you think of it. Reykjavík is a lively little city, but its frisky music scene, what Icelanders call jammið, is confined to a handful of clubs in the “101” district: Café Rosenberg, Kaffibarinn, Bar 11, Dillon, Den Danske Kro, The Celtic Cross, The English Pub. After making the rounds, people stagger outside to find a hot dog or a crushed sheep’s head as a post-gig snack. The hard-drinking Icelanders take their jammið seriously. Bands and audiences mix freely in this profoundly informal and egalitarian country. This small, but intense scene has produced phenomena like the Sugarcubes and Björk, Mínus, Sigur Rós, Quarashi, Sálin, Botnleðja, Maus, Agent Fresco, Samaris, Mammút, and Jakobínarína.

Ingólfr Arnarson founds the first settlement at Reykjavík in 874 A.D., laying the groundwork for jammið and the Icelandic music scene. He appears to be standing precisely at the spot where Kaffibarinn stands today. An 1850 painting of dubious historical accuracy by Johan Peter Raadsig.

In 2010, a new band emerged at the Músíktilraunir, an annual battle of the bands. Of Monsters and Men is comprised of two lead singers/guitarists, Anna Bryndís Hilmarsdóttir and Raggi Þorhallsson, Brynjar Leifsson (guitar), Kristján Páll Kristjánsson (bass), and Arnar Rósenkranz Hilmarsson (drums). Their sound was polished from the beginning, solid indie rock in roughly the same vein as Muse or Mumford & Sons, maybe Death Cab for Cutie. Within a year, they had their first album out, My Head Is an Animal, and it took the world by storm. “Little Talks”, “Dirty Paws”, “Mountain Sound” got extensive airplay in major world markets, and all the other cuts were quality work. Fame, world tours, and movie soundtracks followed. But this sort of instant success is a notorious peril for a good band. For three years, no second album. Music critics and “serious” listeners forgot about them. I heard the singles, but not the whole album until the spring of last year. It bowled me over. An intense, passionate sound, catchy melodies, serious lyrics.

I’m always running behind. There’s so much music to listen to. But I’ve just now heard the long-delayed second studio album, Beneath the Skin, released in the summer of 2015, as well as Live from Vatnagarðar, which was released on a small scale in 2013. I like the new album even better than the first. The music is more restrained, more introspective, not as grab-you-and-shake-you as the first round, but three cuts (“Crystals”, “Human”, and “I of the Storm”) have just as much hit-potential as their forerunners. I was particularly taken, however, by the quieter “Backyard” and “Winter Sound” (which kind of reminded me of some old Wall of Voodoo songs). Beneath the Skin, I hear, did very well with both critics and record-buyers. They did best of all here in Canada, where the album went gold and reached #1 on the charts. Most Icelanders are fluent in English, and use it both to access and communicate to the outer world. All the songs on the two studio albums are in English.

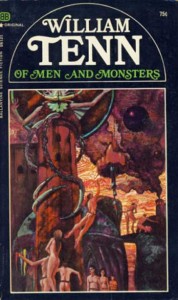

One thing has puzzled me. I’ve encountered no explanation of the band’s name, other than that Raggi suggested it. Had he read the brilliant little science fiction novel Of Men and Monsters, by William Tenn? It came out in 1968, and has stayed in print. I read it as a kid, and reread it six years ago. It’s a little masterpiece, with a razor’s edge balance of satire and tragedy, cynicism and hope, and is one of the best fables of the Little Guys against the Big Thing you can read. Much of it would fit the moods that the band achieves in their music.

If you’ve never encountered this old SF classic, you have a pleasurable experience awaiting you. I reviewed it here in this blog.

0 Comments.