Back in London (or Llundain, in Welsh), and I headed back to Camden Town, hoping to get a spot in the same “cheap” (by London standards) hostel. This proved successful, and I left my pack in storage while I spent another day exploring the city.

I had determined that the only cost-effective way of traveling in London is to buy a day pass for the bus system, and stay out of the costly Underground entirely. Buses move slowly, but once you figure it out, the spaghetti-like maze of routs is actually quite rationally planned. And from the top of double-deckers, you see a lot, and get a chance to orient yourself that the “tube” does not provide.

Since my previous explorations where in the west end of the center city, this time I concentrated on the east. I took a bus to Elephant & Castle, south of the Thames, then walked north across London Bridge, into The City. This is the district that comprises the actual “City of London”, and corresponds fairly closely to the boundaries of Roman Londinium. It’s the historic financial center of England, which is why English businessmen are said to “work in the City”. They have abandoned their bowler hats, but the current dress code still makes them look like flocks of penguins.

In fact, there is another, newer financial district further east, which has an impressive cluster of office towers. There are some modern buildings in The City, too, but they are scattered about randomly. Some are very striking, and one, at 30 St. Mary Axe, is more adventurous in design than anything in Toronto. It looks like a giant alien seed pod that has crash-landed. It should look jarringly out of place, but somehow the effect is satisfactory.

I don’t really care for Christopher Wren’s style, but I must admit that St. Paul’s is an impressive cathedral, and the peeling of its carillon was very harmonious. But I was drawn to another carillon, which was ringing simultaneously, several blocks away. This was at the church of St. Lawrence Jewry, near the Guildhall.

I don’t really care for Christopher Wren’s style, but I must admit that St. Paul’s is an impressive cathedral, and the peeling of its carillon was very harmonious. But I was drawn to another carillon, which was ringing simultaneously, several blocks away. This was at the church of St. Lawrence Jewry, near the Guildhall.

Tourists in London are drawn to Buckingham Palace and the Tower. Both of these are symbols of British monarchy. I was after a different symbolism. The issues I was discussing in the last entry boil down to the struggle between Crown and Parliament that is obviously going on in the U.S., and influencing events in Canada. I was searching for the Guildhall, because it represents the parliamentary side of the equation.

The Guildhall, a medieval (though much rebuilt and modified) building on the cite of an ancient Roman ampitheatre, is the historic town hall of the City of London. It represents, at least in my mind, the struggle between monarchy/aristocracy and democracy, because it was the locus of assertions by the city of its independence from feudal restrictions. There was a saying common in the middle ages: City air makes free. The Guildhall, in many ways, is a kind of architectural embodiment of the Magna Carta. It has more meaning for me the more impressive monuments that people seek out in London.

Prominent in its decoration are representations of Gog and Magog, enigmatic figures from the bible who are found in many Jewish, Christian and Islamic folk traditions. The giants Gog and Magog are guardians of the City of London, and images of them have been carried in the Lord Mayor’s Show since the days of Henry V. The Lord Mayor’s account of Gog and Magog says that the Emperor Diocletian had thirty-three wicked daughters. He married them off to keep them under control. But, led by the eldest, Alba, they murdered their over-controlling husbands. As punishment for this, they were cast adrift at sea, and ended up on a distant isle, which they named Albion, after Alba. Here they mated with demons, and gave birth to a race of giants, among whose descendants were Gog and Magog. The task of the giants is to defend the rights of the citizens — implicitly from the demands of the King and Aristocracy.

Nearby, I came across the Old Bailey, which is familiar to anyone who has read the Rumpole of the Bailey novels of John Mortimer, or seen their television adaptations with the inimitable performances of Leo McKern. The Old Bailey is a narrow lane where one can find the Central Criminal Court of London, as well as the dingy little pubs where barristers, prosecutors and judges lubricate the complexities of British Common Law. This legal tradition, founded on Magna Carta, is the source of law in many countries, including my own. From this traditional body of law, we have inherited the critical concept of habeas corpus, essential for the preservation of liberty. The present Royalist administration in the United States has unleashed vicious and systematic attacks on habeas corpus. The atrocities of Abu Ghraib and the obscenity of Guantanamo Bay are open assaults on habeas corpus, and thus on the fundamental freedoms of all Americans, far more than they are intended to combat terrorism.

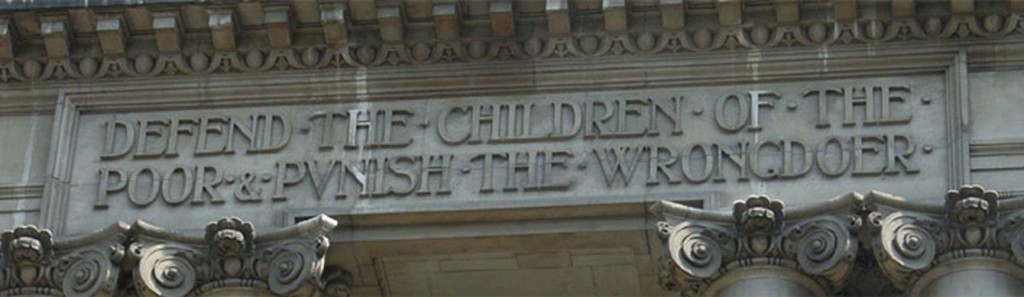

The Court building itself is unimpressive. In fact, it’s a downright ugly Victorian building, but it has a fine motto carved above its door: Defend the Children of the Poor and Punish the Wrongdoers. How much of that has actually occurred under its roof is hard to say, but at least the intention is stated.

London’s back lanes provide endless little surprises. At the shadowy corner of Cock Lane and Guiltspur Street, I found a small gilded statue of a chubby, naked child on the corner of a building. It was erected in 1666 on a pub called The Fortune of War, which later became the hangout of the Resurrectionists, or body-snatchers. Supposedly the stolen bodies were laid out among the tables where they quaffed their pints. This pub was demolished, but the statue built into the present structure. It marks the ending edge of the Great Fire. The fat child represents the claim, made on its inscription, that the fire was caused by The Great Sin of Gluttony (and not so much the Papists, as other monuments claim).

0 Comments.