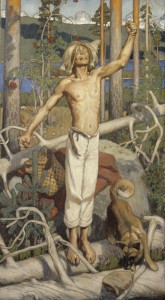

Kullervo is the darkest character in the Kalevala, the epic of Finnish mythology that had a profound effect on me in childhood. His story is told in runos 31 through 36 of the epic. Enslaved and abused as a child, Kullervo’s life is dominated by the quest for revenge, which leads him to commit horrifying crimes, including the rape of his own sister. The most striking part of the story is his death, where he asks his sword if he should kill himself, and the sword bursts into song:

“Mieks’en söisi mielelläni,

“Mieks’en söisi mielelläni,

söisi syylistä lihoa,

viallista verta joisi?

Syön lihoa syyttömänki,

juon verta viattomanki.”

“Why, if I desire it,

should I not kill you,

swallow up your wicked blood?

I have consumed innocent flesh,

and swallowed up guiltless blood.”

This little sequence was borrowed by Poul Anderson in The Broken Sword, and by Michael Moorcock in one of his Elric tales. Väinämöinen, the wise central character of the Kalevala, remarks that Kullervo’s fate proves that children should never be mistreated, since an abused child will grow up without wisdom or honour.

In 1892, the young and unproven composer Jean Sibelius composed Kullervo, a symphonic poem for soloists, chorus and orchestra, Op.7. Finland was still a provincial place, an unwilling dependency of the Russian Empire, isolated from the mainstream of European culture by its remote location and bizarre, non-Indo-European language. It could barely put together an orchestra and chorus capable of handling a work on this scale, and Sibelius demonstrated extraordinary ambition and chutzpah to get it performed. The Finns were just beginning to assert their independence and pride. The work had strong nationalist (i.e. subversive, to the Russian authorities) overtones.

Sibelius was later embarrassed by the work, which he regarded as an amateurish youthful effort. It was not often performed in his lifetime. But after his death, it was revived, as people discovered its extraordinary vitality. Yes, it has some amateurish awkwardness, but it is a hell of a spectacular show, and for a work by a young composer, it showed amazing command of orchestral forces. There are obvious borrowings from the composers that influenced him as a student, especially Tchaikovsky, but Sibelius’ unique voice is already there. The choral passages are magnificent, and unlike most choral interpretations of epic verse, they are right-sounding. It is as if the runos of the Kalevala were intended, all along, to be sung this way.

I possess two versions, one directed by Paavo Berglund, which I first heard when I was discovering Sibelius, as a teenager. Another version, directed by Jorma Panula, is not quite as good, but quite acceptable, and available on a bargain Naxos cd. I regret that I haven’t heard the version by Jukka-Pekka Saraste, the brilliant conductor who led the Toronto Symphony during the unfortunate period when its finances were troubled and labour relations went sour. I once heard him perform Sibelius’ Fifth in a mesmerizing, almost supernatural performance. This is not a deep work, like the Fifth, but I imagine that Saraste would interpret it perfectly. Colin Davis, perhaps the best non-Finnish interpreter of Sibelius, also has a version.

0 Comments.