Stephen Fry has the kind of effortless talent that makes me envious. He is a brilliant actor and comedian (Blackadder; Jeeves and Wooser; A Bit of Fry and Laurie), and fine writer of fiction, non-fiction, screenplays and plays (I’m in the middle of his novel Making History). Naturally, such a person would be expected to write an interesting biography. But I was unprepared for the extreme honesty and sparkling wit of this book. It’s devoted entirely to his childhood and teenage years, always the most interesting parts of an autobiography, if it is honest. His description of his first experience of feeling love is among the finest I’ve read. His self-evaluations strike me as spot-on, his confessions to misdeeds are not twisted into self-glamorizing. The book is absolutely engrossing. For the aspects of human culture that offend him, he reserves a special, eloquent anger: Read more »

Category Archives: BP - Reading 2006 - Page 2

14800. (Jon George) Zootsuit Black

This is Jon George’s second novel, which I read eagerly after being very pleased by Faces of Mist and Flame. This one is much more complicated, juggling several characters and situations. The plot involves a sudden alteration in the fabric of reality, experienced by the whole earth, a character trying to pin down the nature of psychic abilities, and characters flashing on events in the past. Among those events is the assassination of SS–Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich, who was perhaps the principal architect of the Holocaust. This fascinated me. I not only made a study of the Wansee Conference, where Heydrich consolidated his plans, but a friend showed me the exact spot in the Prague suburb of Kobylisy where he was shot by Czech partisans. I will recommend this novel, especially to anyone who has already read Faces of Mist and Flame, with the caveat that its narrative complexity requires more attentive reading.

READING – SEPTEMBER 2006

14749. (Cory Doctorow) Someone Comes to Town, Someone Leaves Town

14750. (Joseph Kage) Chapitre Premier: Esquisses de la vie Canadienne sous Le Régime Français

14751. (David G. Hubbard) The Skyjacker, His Flights of Fancy

(Bernard DeVoto) Mark Twain At Work:

. . . . 14752. (Bernard DeVoto) The Phantasy of Boyhood: Tom Sawyer [article]

. . . . 14753. (Mark Twain) “Boy’s Manuscript” [fragment anticipating Tom Sawyer]

. . . . 14754. (Bernard DeVoto) Noon and the Dark: Huckleberry Finn [article]

. . . . 14755. (Bernard DeVoto) The Symbols of Despair [article]

14756. (Robert Graves) I, Claudius

Read more »

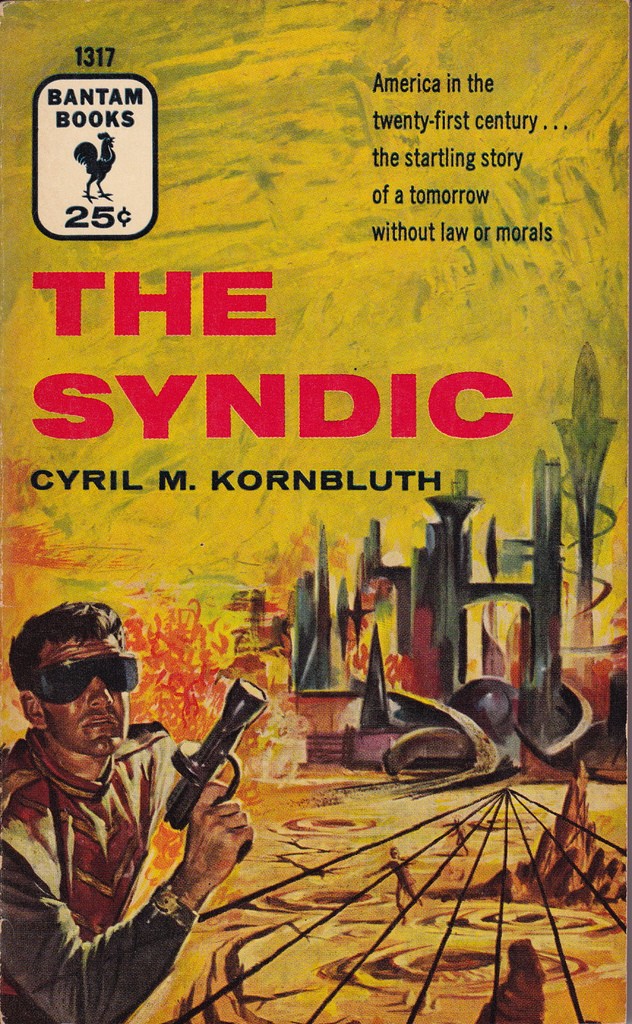

14777. (Cyril M. Kornbluth) The Syndic

There was something absolutely wonderful about the kind of science fiction that was published in the American SF magazines in the 1950’s. While the “mainstream” fiction writers struggled to obey increasingly rigid notions of “realism” and the short story virtually disappeared as an art form in the literary world, Science Fiction writers flourished in their small ghetto, free to let their imaginations roam, and free to satirize society with infinite jest. That wonderful creative cauldron gave us Theodore Sturgeon, Philip K. Dick, Avram Davidson, Edgar Pangborn, William Tenn, Alfred Bester, and many, many more. These were among the finest writers America ever produced. There was one writer that almost all these men looked up to and admired, and that was Cyril M. Kornbluth. Sadly, his career ended with premature death in 1958, after only seven years of writing. But in those seven years he produced several masterpieces in collaboration with Fredrik Pohl —such as the brilliant satire of advertising, The Space Merchants, and the remarkably prescient Gladiator-at-Law. He also produced several fine novels on his own, much more biting (perhaps because Pohl’s mellower personality influenced the collaborations), as well as a plethora of brilliant short stories. ‘The Little Black Bag’ and ‘The Marching Morons’ are perfect examples of his superb artistry.

There was something absolutely wonderful about the kind of science fiction that was published in the American SF magazines in the 1950’s. While the “mainstream” fiction writers struggled to obey increasingly rigid notions of “realism” and the short story virtually disappeared as an art form in the literary world, Science Fiction writers flourished in their small ghetto, free to let their imaginations roam, and free to satirize society with infinite jest. That wonderful creative cauldron gave us Theodore Sturgeon, Philip K. Dick, Avram Davidson, Edgar Pangborn, William Tenn, Alfred Bester, and many, many more. These were among the finest writers America ever produced. There was one writer that almost all these men looked up to and admired, and that was Cyril M. Kornbluth. Sadly, his career ended with premature death in 1958, after only seven years of writing. But in those seven years he produced several masterpieces in collaboration with Fredrik Pohl —such as the brilliant satire of advertising, The Space Merchants, and the remarkably prescient Gladiator-at-Law. He also produced several fine novels on his own, much more biting (perhaps because Pohl’s mellower personality influenced the collaborations), as well as a plethora of brilliant short stories. ‘The Little Black Bag’ and ‘The Marching Morons’ are perfect examples of his superb artistry.

A fine introduction to Kornbluth’s work would be this novel, The Syndic, published in 1953. It posits a future in which governments have collapsed under their own weight of bureaucracy and been replaced by the Mafia. In 1953, it was far-out whimsy. How would an Eastern European read it today? The real pleasure in reading Kornbluth is that his sharp satire is delivered in a crisp, purely colloquial style, as if Damon Runyan where writing sociological Science Fiction. A serious writer, today, would make heavy going of this stuff, stretching it out and filling it with stylistic tricks and learned references. Kornbluth wrote like an experienced barber.… a few deft strokes with a very sharp blade, done like magic, and over before you can catch your breath. Fifty-three years have passed since this novel hit the stands, and it is not quaint. It’s still a good, clean shave.

A fine introduction to Kornbluth’s work would be this novel, The Syndic, published in 1953. It posits a future in which governments have collapsed under their own weight of bureaucracy and been replaced by the Mafia. In 1953, it was far-out whimsy. How would an Eastern European read it today? The real pleasure in reading Kornbluth is that his sharp satire is delivered in a crisp, purely colloquial style, as if Damon Runyan where writing sociological Science Fiction. A serious writer, today, would make heavy going of this stuff, stretching it out and filling it with stylistic tricks and learned references. Kornbluth wrote like an experienced barber.… a few deft strokes with a very sharp blade, done like magic, and over before you can catch your breath. Fifty-three years have passed since this novel hit the stands, and it is not quaint. It’s still a good, clean shave.

14751. (David G. Hubbard) The Skyjacker, His Flights of Fancy

In the late 1960’s, there was a wave of “skyjackings” — where lone gunmen would force airplanes to fly to Cuba. This book was a contemporary psychiatrist’s attempt to analyze the motivations of the Skyjackers, based on interviews with them in jail. In most cases, Cuba simply extradited them to Canada, which then extradited them to the United States. Even at the time, it was understood by everyone that the skyjackings were not initiated by, or encouraged by the Castro regime, which was actually rather embarrassed by the phenomenon. The author rejects the idea that there was any serious political motivation behind the skyjackings. In most cases, the political proclamations of the perpetrators were far too shallow and silly to be taken seriously as motives. He goes through the personal history of each skyjacker and finds that they are remarkably uniform. The typical skyjacker was the child of a violent, bullying father and a deeply religious mother, who subsequently failed miserably in carving out any kind of success. They were usually obsessively religious, and socially and psychologically extremely conservative. Their sexual lives, most of the time, were pathetic. After some particularly devasting failure or betrayal, they quite spontaneously concocted a scheme to create a dramatic event that would somehow, they felt, resolve their difficulties, at least in a symbolic sense. The idea of the skyjackings seems to have occured to them simply because others had done it, and it was a big thing in the news. The similarity to the psychological profiles of serial killers, discussed in Elliott Leyton’s work, is striking. Leyton would have had a more common-sense approach to the case histories. Hubbard used his data to concoct a rather lame theory from the pseudo-science of psychotherapy which was then still very influential. But the case histories speak for themselves, and it’s interesting for a reader in 2006 to be reminded that air travel was not particularly safe forty years ago.

14749. (Cory Doctorow) Someone Comes to Town, Someone Leaves Town

This is an extremely imaginative and well-written novel, pulling together several themes that would not normally work well together. Doctorow combines a realistic representation of life in Toronto’s pleasantly chaotic Kensington Market neighbourhood with nightmarish fantasy elements that have the feeling of the grimmer parts or Norse, German or Native Canadian folklore, and throws in a little cyberpunk, as well. These disparate components are not set apart in blocks, but flow and blend into each other on a paragraph-by-paragraph, sometimes a sentence-by-sentence basis. I won’t summarize the plot: it will just sound arbitrarily grotesque, and will not give you any hint of the humanity and the effective language of the book. The book gives me some hope, because I was feeling that Science Fiction writing in North America was moribund, and this is an example of a returning vigour.

READING – AUGUST 2006

14719. (Brian Doyle) Easy Avenue

14720. (Mary Mapes) Truth and Duty ― The Press, the President, and the Priviledge of Power

(Walter Mosley) Futureland: Nine Stories of an Imminent World:

. . . . 14721. (Walter Mosley) Whispers in the Dark [story]

. . . . 14722. (Walter Mosley) The Greatest [story]

. . . . 14723. (Walter Mosley) Doctor Kismet [story]

Read more »

14746. (Elliott Leyton) Hunting Humans

This is the seminal work on the anthropology and sociology of serial killing. I read it in conjunction with an NFB documentary film “The Man Who Studies Murder”, which puts a face to the voice of the book. Leyton is a country boy from small-town Saskatchewan (who looks and sounds distinctly Metis, though I can’t say for sure that he is) and now lives in Newfoundland. Newfoundland is rural, poor by North American standards, and virtually every house has a gun. Economically, it’s the Canadian equivalent of Arkansas. But it has one of the lowest murder rates in the world. In the film, Leyton discusses the reasons why he considers cultural choices and mores the principal determinant of murder rates and styles of murder, often using his home as a laboratory.

The book on serial and mass killers, dealing with the “classic” cases, attempts to get beyond the kind of unverifiable psychiatric speculations that dominated the issue before Leyton came on the scene. As he demonstrates, psychiatry has been of little use in understanding the phenomenon. He shows the fundamental similarities in most serial killings, and does his best to deflate the nonsense generated by Thomas Harris’s “Hannibal Lecter” fantasies. Serial killers are invariably pathetic, ineffective losers, usually pretty dumb.…. never the suave supergeniuses of fiction. Leyton rejects biological and psychiatric explanations in favour of a cultural one, and argues it persuasively. He may not have the last word on this issue, but his opinions are more worth reading than most. He is also a witty and entertaining writer ― and from the evidence of the film, has the same qualities in person.

Tuesday, August 22, 2006 — The Ideology of Qutb

I just finished reading Sayyid Qutb’s Ma’alim fi-l-Tariq [“Milestones”]. This book is not available in my public library system. Since it bears the same relationship to the rise of Islamist totalitarianism as Mein Kampf and The Communist Manifesto do to European totalitarianism, you would think it would be smart for our libraries to have it. You cannot resist a movement of oppression and aggression by knowing nothing about it. Milestones is the ideological entry-point by which bored, spoilt-brat teenagers in Muslim families are drawn into the movement and converted into zealots for death and destruction. It should be read, grasped, and understood by sane people, so that its insanity can be countered. Read more »

14737. (Joseph Boyden) Three Day Road

This book caught my eye because it’s heroes are from the coast of Hudson’s Bay, a nostalgic place for me. Two Cree lads from Moose Factory fight in the trenches of World War I. Boyden writes beautifully, is familiar with Cree culture, and researched WWI trench warfare with a historian’s skill. The book compares well with the classic Canadian novel of WWI, Timothy Findlay’s The Wars. The Great War of 1914–1918 had a tremendous impact on Canada — far more than on the United States. Canada was involved during the entire length of the war, had twice as many soldiers on the front per-capita as the U.S., and one Canadian family in five suffered a casualty. The war ended the desire of most Canadians to keep any serious political ties with Britain, and scarred an entire generation. So it isn’t surprising that WWI novels continue to be written, and loom large in Canadian literature. This is a worthy example. Read more »