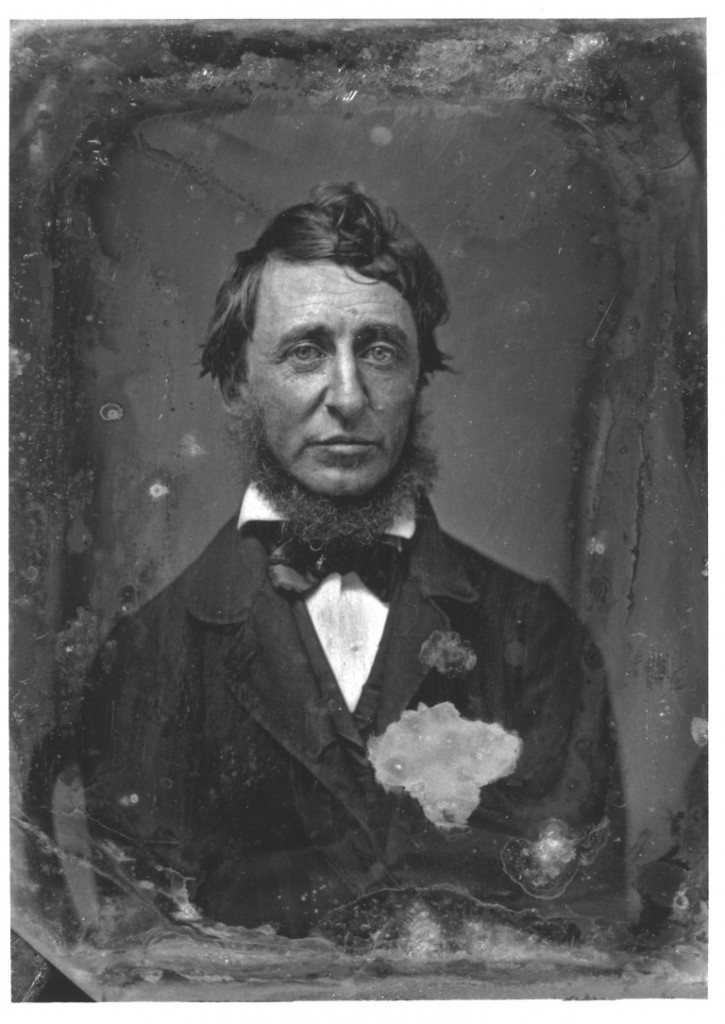

Thoreau is one of those people that you might read as a teenager, then keep in the back of your mind for the rest of your life. But do you get around to re-reading him later in life? One thing that strikes me now, on rereading him, is how much he gets distorted by false memory. How many people have decided that the ideal life is on a farm, and talk about Thoreau and “simplicity”? But for the actual Thoreau, farm life was the complex rat race he was fleeing from! He complained that everyone he knew was carrying a barn on their back. One man’s simplicity is another man’s 1984, I suppose. The economist John Kenneth Galbraith who had grown up on one of those dour Scottish-Canadian farms in southern Ontario once explained that after milking cows with frozen teats on subzero mornings and bailing hay by hand, nothing he ever did as an adult was classifiable as work, and he would much rather be a professor than go back to that simplicity, thankyou very much. I did my own fair share of farm work, and even with more modern machinery, I know exactly what he meant. Try standing up to your knees in half frozen sheep shit while cold drizzle soaks into you, for an entire day, while you wrestle fiercely kicking animals to the ground, one after another. Simplicity, indeed.

Thoreau is one of those people that you might read as a teenager, then keep in the back of your mind for the rest of your life. But do you get around to re-reading him later in life? One thing that strikes me now, on rereading him, is how much he gets distorted by false memory. How many people have decided that the ideal life is on a farm, and talk about Thoreau and “simplicity”? But for the actual Thoreau, farm life was the complex rat race he was fleeing from! He complained that everyone he knew was carrying a barn on their back. One man’s simplicity is another man’s 1984, I suppose. The economist John Kenneth Galbraith who had grown up on one of those dour Scottish-Canadian farms in southern Ontario once explained that after milking cows with frozen teats on subzero mornings and bailing hay by hand, nothing he ever did as an adult was classifiable as work, and he would much rather be a professor than go back to that simplicity, thankyou very much. I did my own fair share of farm work, and even with more modern machinery, I know exactly what he meant. Try standing up to your knees in half frozen sheep shit while cold drizzle soaks into you, for an entire day, while you wrestle fiercely kicking animals to the ground, one after another. Simplicity, indeed.

On rereading, I found Walden and Civil Disobedience to be pretty much as I remembered them. Thoreau made it clear in Walden that he was making an experiment in self-discipline, not designing a blueprint for everyone to live by. He had enough sense to know that if everyone tried to live off the beans in their backyard, the result would be grinding medieval poverty, not independence. He was not going off to live in a cave. He walked to town every day to see his friends, and he even went off on lengthy jaunts of tourism.

His travel journals contain some of his most entertaining writing. His prose style is remarkably modern-sounding for the 1850s. His observation of sensory detail was also unusual for the period. A reader having no appropriate clues might place the prose style at circa 1910. “A Yankee In Canada” describes the Charlevoix region north of Quebec City, a place I did a few hundred kliks of walkabout in, with Filip Marek. Thoreau spoke French reasonably well (he was of Channel Island ancestry), and asked questions everywhere. He was not only pre-occupied with nature, which describes with precision, but with economic and social facts as well. For example, he noted that the voting franchise was wider in Canada East than in New England, that the British still treated Quebec as a garrison town (it is still 17 years before Confederation), and which varieties of fruits and cloth were imported and exported.

One thing he got ironically wrong. He noticed a large number of stone Churches, imagining them to be a legacy of Normandy. But, in fact, most of the original churches of Quebec had been made of wood, in a simple style improvised by the Habitants. Over the next two centuries, most of these churches succumbed to the inevitable fires, and only a handful of them survive today on the Ile d’Orleans. But the style survived. The English settlers of New England, also coming from a land of stone churches, copied the Quebec wooden churches, perfecting them into the distinctive white Congregational jewels that still make many New England villages sublimely beautiful. The pretty stone and tin-roofed churches that Thoreau saw along the St. Lawrence were mostly built shortly before he saw then.. They are usually painted white in the trimmings, and built of pale gray stone, so that a Quebec village has a visual charm almost as striking as a Vermont one, but the effect is different. The “strip village” dominates in Quebec, following riverbanks, evolved from farm lots that are narrow on the roads, but extend for miles back into the forest. This configuration is critical in harsh winters, when the walking time to the nearest neighbour can determine life or death. By contrast, New England villages focus on a square, and are much more compact, but outlying farms must be serviced by more road mileage. He was, of course, fascinated by the Catholicism in Canada, as any New Englander would be, but he was not hostile. He was equally fascinated by the omnipresent kilted Scots Highlanders, having apparently never seen so many bare male legs.

But Thoreau’s prose is wonderful, and you can just picture yourself having a cheerful afternoon poking around in the woods with him. He claimed to have been a happy man, and perhaps he wasn’t lying.

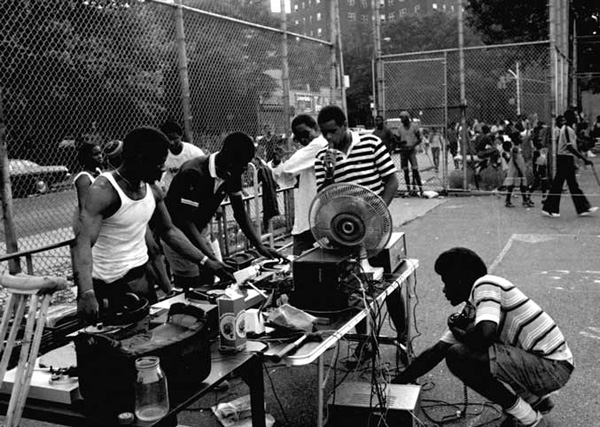

A straightforward history of the early days of Hip Hop, focusing more on the producers, record labels and people who ran the business end than on the performers. Hip Hop seems to have coalesced into existence simultaneously in several U.S. cities in the early seventies, but a conventional “birthday” is the August 11, 1973 party in a basement apartment in the Bronx. Soon, people DJs like Afrika Bambaataa and Kool Herc were throwing block parties featuring breakbeats and scratching. Emcees, began spontaneously rapping to the beats.Through the seventies, it was a spontaneous, informal and barely noticed seen…it was six years before the first Hip Hop album was recorded and released. As the musical fashion saturated the world, money started piling up, and the inevitable struggle between art, social conscience, and business interests. This is the part that interests the author. His analysis is common sense: money soon overwhelms art and social causes.

A straightforward history of the early days of Hip Hop, focusing more on the producers, record labels and people who ran the business end than on the performers. Hip Hop seems to have coalesced into existence simultaneously in several U.S. cities in the early seventies, but a conventional “birthday” is the August 11, 1973 party in a basement apartment in the Bronx. Soon, people DJs like Afrika Bambaataa and Kool Herc were throwing block parties featuring breakbeats and scratching. Emcees, began spontaneously rapping to the beats.Through the seventies, it was a spontaneous, informal and barely noticed seen…it was six years before the first Hip Hop album was recorded and released. As the musical fashion saturated the world, money started piling up, and the inevitable struggle between art, social conscience, and business interests. This is the part that interests the author. His analysis is common sense: money soon overwhelms art and social causes.