Back in the mid-1980’s, I became very interested in the native cultures of Siberia, partly because they have many similarities with the native cultures of northern Canada. I went so far as to correspond with several people in Siberia, something which was just then beginning to be possible. This was necessary, because there was then very little information available in English or French about this region, most of which had been sealed off by the Communist regime for most of the century. Some very nasty things happened there, not the least of which was the wholesale suppression and destruction of native cultures. I dug up the small number of relevant books and articles that I could, but there wasn’t much to be found. Read more »

Category Archives: B - READING - Page 32

16215. (Edward J. Vajda) Yeniseian Peoples and Languages; 16216. (Edward J. Vajda) Ket

16200. (Peter Bellwood) The First Farmers

I’ve been reading everything I can find on this subject for months, now, and this is by far the best book I’ve seen. It is modifying some of my views, and re-enforcing others. It will take me some time to absorb and reflect on the material, here, so I will not leap to a conclusive judgment until it has been well-mulled. Whatever your views on the subject of the neolithic transition to agriculture, this book is essential reading. It brings together the main blocks of evidence (from archaelogy, linguistics, genetics, paleoclimatology, skeletal anthropology, plant and animal biology) in a balanced and systematic way. In most cases, Bellwood lets the evidence speak for itself, and draws conclusions only when they seem compelled by the facts. I think he is missing a major theoretical element, if my hunches remain consistent with the evidence as it stands. But I think this will require more saturation in the existing literature, before I start mouthing off. I’m an amateur and an outsider. This can be an advantage, in certain circumstances, as the history of science has shown, but it is also very easy for an amateur to drift into crankery — which I hope never to do.

16197. (Frances Stonor Saunders) The Devil’s Broker ― Seeking Gold, God, and Glory in 14th Century Italy

This is a very well-written study of the role of the English condottieri who were the Haliburton Gang of fourteenth century Italy. It focuses on the character of John Hawkwood, a minor English knight who rose to leadership among the mercenary armies that were cast loose on France and Italy, when the Hundred Years War entered a lull. Saunders’ prose is excellent, and evocative, her grasp of the evidence is strong, and she has a common-sense vision of the real life behind the documents. Read more »

READING – APRIL 2008

15976. (Timothy Findley) Famous Last Words

15977. (Richard E. Michod) Evolution of the Individual [article]

(W. H. Wills & Robert D. Leonard) The Ancient Southwestern Community ― Models and

. Methods for the Stury of Prehistoric Social Organization:

. . . . 15978. (W. H. Wills & Robert D. Leonard) Preface [preface]

. . . . 15979. (Ben A. Nelson) Approaches to Analyzing Prehistoric Community Dynamics

. . . . . . . . [article]

. . . . 15980. (Elizabeth A. Brandt) Egalitarianism, Hierarchy and Centralization in the

. . . . . . . . Pueblos [article]

. . . . 15981. (Dean J. Saitta) Class and Community in the Prehistoric Southwest [article]

. . . . 15982. (Katherine A. Spielman) Clustered Confederacies: Sociopolitical Organization

. . . . . . . . in the Protohistoric Rio Grande [article]

. . . . 15983. (Barbara J. Mills) Community Dynamics and Archaeological Dynamics: Some

. . . . . . . . Considerations of Middle-Range Theory [article] Read more »

16140. (Marc Bekoff) The Emotional Lives of Animals

Both compact and comprehensive, this is the first book you should read to enter into the interesting science of cognitive ethology. Bekoff summarizes the reductionist strictures that ethologists had to confront when the field began to form, and intelligently discusses the moral and social implications of the science. The book, in effect, provides a case study of the cult of “scientism”, which often infected science in the twentieth century. This occurred when fake poses of objectivity, spurious quantification, and epistemological confusion led to nonsensical, but irritatingly tenacious orthodoxies.

(Nathaniel Hawthorne) The Celestial Railroad and Other Stories

Hawthorne’s allegorical short stories were, in some ways, the ancestors of some of the grimmer Twilight Zone episodes. This collection includes stories written between 1832 and 1851, and includes the most famous ones, “Young Goodman Brown” , “Ethan Brand”, “Rappaccini’s Daughter”, and “Dr. Heidegger’s Experiment”. All fine stories, but the one that tickled my fancy was the less well known “The Maypole of Merry Mount”. It’s a sort of 1836 version of The Wicker Man, except that the Puritans, not the Pagans, triumph. It is all the more interesting because Hawthorne seems to have been well aware of things that would not be part of common knowledge until James Frazer published The Golden Bough. Read more »

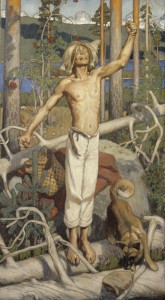

Sibelius’ Kullervo, Op.7

Kullervo is the darkest character in the Kalevala, the epic of Finnish mythology that had a profound effect on me in childhood. His story is told in runos 31 through 36 of the epic. Enslaved and abused as a child, Kullervo’s life is dominated by the quest for revenge, which leads him to commit horrifying crimes, including the rape of his own sister. The most striking part of the story is his death, where he asks his sword if he should kill himself, and the sword bursts into song:

“Mieks’en söisi mielelläni,

“Mieks’en söisi mielelläni,

söisi syylistä lihoa,

viallista verta joisi?

Syön lihoa syyttömänki,

juon verta viattomanki.”

“Why, if I desire it,

should I not kill you,

swallow up your wicked blood?

I have consumed innocent flesh,

and swallowed up guiltless blood.”

This little sequence was borrowed by Poul Anderson in The Broken Sword, and by Michael Moorcock in one of his Elric tales. Väinämöinen, the wise central character of the Kalevala, remarks that Kullervo’s fate proves that children should never be mistreated, since an abused child will grow up without wisdom or honour. Read more »

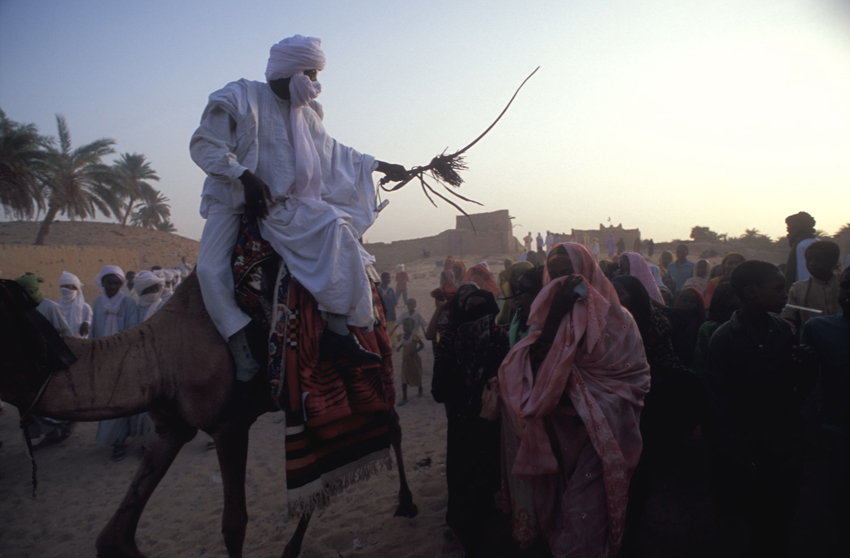

Monday, April 14, 2008 — Jeune Afrique 8 avril 2008 AFP: Les députés modifient la Constitution pour juger Hissène Habré — A Personal Ghost Comes Back in a Brief News Report

It seems that a relentless treadmill of events forces me to write, in this blog, about nothing but dictators, famines, and wars. For those of you who are tired of it, let me confess that I am, too. I wanted to devote a new entry to one of my real passions ― landscape, music, reading, nature, erotic pleasure, the exquisite freedom of the road. But an article forwarded to me unleashed a flood of memory and opened up private boxes that I’ve generally kept shut. And it was about a dictator. Now, I write a lot about dictators, and the observant among you will notice that I don’t much like them. But, in most cases, this is the result of studying history. Dictators are people I’ve mostly encountered in books. But there is one exception. There is a dictator with whom my relationship is more concrete, and has nothing to do with books. He is one of the “small-fry”. His crimes are monstrous, but his numerous victims were people the world cared nothing about. The slaugther and horror took place right next door to the current slaughter in Darfur, and was on the same scale, but in those pre-internet days it might as well have taken place in another solar system. The man I’m talking about is Hissène Habré.

16106. (David Matas & Hon. David Kilgour) Bloody Harvest: Revised Report into Allegations of Organ Harvesting of Falun Gong Practitioners in China [report]

David Kilgour has been one of Canada’s longest serving Members of Parliament (27 years), as a Cabinet Minister, and as Secretary of State for Asia-Pacific Affairs. Few Members of Parliament are as widely respected. One journalist has written: “in the past 25 years, no Canadian could take this kind of moral time-test and pass with such flying colours as David Kilgour.” — and no Canadian politician comes even close to him as a consistent and principled advocate of human rights. He has published four books on varied subjects, ranging from Espionage to Canadian-American relations. David Matas is a lawyer and lecturer on constitutional law, international law, and civil liberties. He was in the Canadian Delegation to the Stockholm International Forum on the Holocaust, and since 1997 has been the Director of the International Centre for Human Rights & Democratic Development. Read more »

15976. (Timothy Findley) Famous Last Words

This was Timothy Findley’s fourth novel, and it attempts to get into the morbid world of the celebrities and intellectuals who cosied up to the Nazis and the Italian Fascists. This was identical, psychologically, to the coterie of celebrities who cosied up to the Communists. It was a loathsome time, in which there were very few voices who spoke for anything good. Everyone was some kind of sleazy creep. Ezra Pound, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, Harry Oakes, Rudolf Hess, and von Ribbentrop appear as characters, among others, all seen through the eyes of a fictional Hugh Selwyn Mauberley (the persona of some of Pound’s poems), whose frozen corpse is found in an Alpine hotel, with a testament scrawled in pencil on the walls of three rooms. It’s a good and intriguing read, but the absence of any character that one can feel any sympathy for left me feeling worn out by the end. But that has always been my response to the intellectual world between the two World Wars. Frankly, I don’t care about the fact that people like Ezra Pound of Bertolt Brecht were talented writers — they were disgusting little pieces of shit, and no amount of cleverness or artistry makes them admirable. The Nazi-Communist-Fascist mentality was the lowest ebb of the human mind, when geniuses degraded themselves into moronic savages. There is probably no way to write about it, or read about it, without feeling ill. We are still suffering the aftereffects of that intellectual holocaust.