This novel pleased me. It’s well-written, the characters come alive, and the author doesn’t pussy-foot. Cunningham takes three characters from childhood, bringing them up to youthful adulthood. They end up forming a precarious family and raise a shild. Nothing very extraordinary happens. But it is all done with great skill. The book is grown-up. As I turned the pages, I was reminded of my protracted struggle with the current situation in Science Fiction publishing. I grew up with Science Fiction, and I would rather write in that genre than write the sort of thing that Michael Cunningham does. Read more »

Category Archives: B - READING - Page 44

14612. (Michael Cunningham) At Home at the End of the World

READING FEBRUARY 2006

14594. (Gavin Menzies) 1421, the Year China Discovered the World

14595. (Louise Levathes) When China Ruled the Seas

14596. (Birgit & Peter Sawyer) Medieval Scandinavia From Converson to Reformation,

. . . . . circa 800‑1500

14597. (Ellis Peters) The Summer of the Danes Read more »

14594. (Gavin Menzies) 1421, the Year China Discovered the World

Farley Mowat engaged in some unrestrained speculation with his “Alban” prehistoric explorers. Now, Gavin Menzies goes absolutely wild with speculation in his “reconstruction” of a gigantic global exploration by the Chinese admiral Zheng He in the year 1421.

Farley Mowat engaged in some unrestrained speculation with his “Alban” prehistoric explorers. Now, Gavin Menzies goes absolutely wild with speculation in his “reconstruction” of a gigantic global exploration by the Chinese admiral Zheng He in the year 1421.

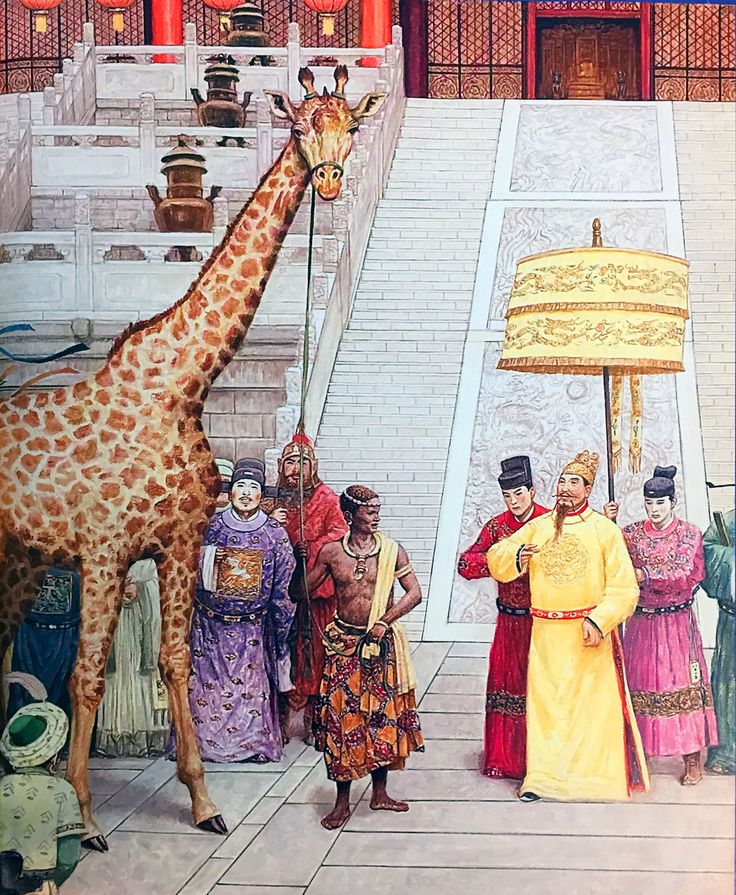

It is well known that a large Chinese Imperial fleet, under the direction of Zheng He (or Heng Ho), the eunuch aide-de-camp of the early Ming emperor Zhu Di, undertook seven long voyages that combined trade, diplomatic and exploratory motives. Chinese trade and exploration of the East African coast is well accepted by historians. Zheng He’s voyages are well documented by his secretary, Ma Huan, whose chronicling of some of the voyages was widely printed and distributed, and there are collateral accounts by Fei Xin and Gong Zhen, both officers on some of the voyages. There is also plenty of corroboration in Ming dynasty public records. Zheng He’s celebrity was such that plays were being performed about him while the voyages were still going, and a century and a half later, an immensely popular historical novel, Journey of the Three-Jeweled Eunuch to the Western Oceans by Luo Maodeng, retold the story with embellishments. Read more »

READING JANUARY 2006

(Stephen Leacock) Behind the Beyond

. . . . 14545. (Donald Cameron) Introduction [preface]

. . . . 14546. (Stephen Leacock) Behind the Beyond, A Modern Problem Play [article]

. . . . 14547. (Stephen Leacock) With the Photographer [article]

. . . . 14548. (Stephen Leacock) The Dentist and the Gas [article]

. . . . 14549. (Stephen Leacock) My Lost Opportunities [article] Read more »

14591. (Farley Mowat) The Farfarers

This is Farley Mowat’s odd book about a possible pre-viking European presence in the Canadian Arctic.

Mowat is very careful to warn the reader that he is engaging in a kind of speculative archaeology. He even intersperses the text with little passages of adventure fiction. But it is also clear that he has convinced himself pretty thoroughly that his speculations correspond to what actually happened. And the result is, of course, one of those books where a chapter begins with the assertion that something might have happened , which by the end of the chapter has been gradually transformed into what certainly did happen , and then becomes the premise for the next chapter, which begins with if that happened, then this might have happened , and so on. Gradually, a huge sequence of suppositions begins to have the appearance of a framework of solid evidence, when it is most clearly not.

What he begins with is something which is verifiably true. The eastern Arctic of Canada is littered with odd ruins and megalithic structures that can not be easily attributed to the Inuit, or to the earlier Dorset or Thule cultures. Nor do they appear to be built by the Norse. They are definitely very old. The most interesting concentrations are on the western shore of Ungava bay, and in a bay immediately south of the spectacular Torngat range, in Labrador. Read more »

14588. (Harry Mulisch) The Discovery of Heaven [= De ontdekking van de Hemel, tr. from Dutch by Paul Vincent]

This is a reasonably interesting novel, though not economically written. It’s a sprawling omnibus of digressions, combining fantasy, mysticism, politics and a kind of Jules et Jim triangle romance. Mulisch is intelligent, learned, and absolutely saturated with conventional systems and intellectual orthodoxy. There is a lot of thought in this book, but not a particle of original thought. This is, unfortunately, supposed to be the great masterpiece of modern Dutch literature. Well, the Dutch have blessed the world with wonderful painting and architecture, and their trance djs are superb, but literature just doesn’t seem to be their strong point. Nevertheless, I might recommend it for a lazy afternoon’s reading. The interaction of the characters is sometimes interesting.

14587. (S. Craig Watkins) Hip Hop Matters ― Politics, Pop Culture, and the Struggle for the Soul of a Movement

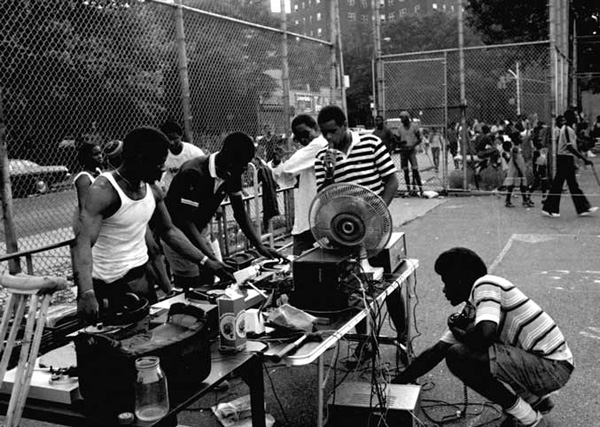

A straightforward history of the early days of Hip Hop, focusing more on the producers, record labels and people who ran the business end than on the performers. Hip Hop seems to have coalesced into existence simultaneously in several U.S. cities in the early seventies, but a conventional “birthday” is the August 11, 1973 party in a basement apartment in the Bronx. Soon, people DJs like Afrika Bambaataa and Kool Herc were throwing block parties featuring breakbeats and scratching. Emcees, began spontaneously rapping to the beats.Through the seventies, it was a spontaneous, informal and barely noticed seen…it was six years before the first Hip Hop album was recorded and released. As the musical fashion saturated the world, money started piling up, and the inevitable struggle between art, social conscience, and business interests. This is the part that interests the author. His analysis is common sense: money soon overwhelms art and social causes.

A straightforward history of the early days of Hip Hop, focusing more on the producers, record labels and people who ran the business end than on the performers. Hip Hop seems to have coalesced into existence simultaneously in several U.S. cities in the early seventies, but a conventional “birthday” is the August 11, 1973 party in a basement apartment in the Bronx. Soon, people DJs like Afrika Bambaataa and Kool Herc were throwing block parties featuring breakbeats and scratching. Emcees, began spontaneously rapping to the beats.Through the seventies, it was a spontaneous, informal and barely noticed seen…it was six years before the first Hip Hop album was recorded and released. As the musical fashion saturated the world, money started piling up, and the inevitable struggle between art, social conscience, and business interests. This is the part that interests the author. His analysis is common sense: money soon overwhelms art and social causes.

An interesting quotation: “Who would pay money for something they can hear for free at parties? Let’s keep it underground. Nobody outside of the Bronx would like this stuff anyway.” —- Joseph Saddler, aka Grandmaster Flash, 1979, when approached with the idea of putting rap music on records.

14586. (Valerio Massimo Manfredi) The Last Legion

An interesting historical novel set in the period of Romulus Augustus, the last Roman Emperor in the Western Empire. The book is translated from Italian. It is fast-paced adventure fiction, written in the spirit of Alexandre Dumas. There is a “surprise” ending, which the reader will probably see coming fairly early in the game. Though most of the action takes place in Italy, it is suffused with the “Matter of Britain”. Doesn’t anyone ever write about late Roman Spain, or Norica, or Africa?

14577. (John Donne) The Selected Poetry of Donne [ed. Marius Bewley]

Donne is best when he writes of love or death, dullest when building “metaphysical” structures or playing games with theology.

Where, like a pillow on a bed,

A pregnant bank swell’d up, to rest

The violet’s reclining head,

Sat we two, one another’s best.

Our hands were firmly cemented

With a fast balm, which thence did spring,

Our eye-beams twisted, and did thread

Our eyes, upon one double-string;

So to intergraft our hands, as yet

Was all the means to make us one,

And pictures in our eyes to get

Was all our propagation.

14576. (Kurt W. Treptow) Vlad III Dracula ― The Life and Times of the Historical Dracula

This seems to be the best book on Vlad III of Wallachia, the historical “Dracula”. It at least explodes the silliest interpretations, put forward by Marxists under the Ceaucescu regime, that seem to have found their way into many secondary sources. Vlad seems to have been a perfectly ordinary little gangster, committing plenty of atrocities, but not much different in style and motivation from those of other thugs ruling principalities. Compared to the colossal outrages of the religious wars that tore Germany apart, soon after, it was all small potatoes.

While Vlad enjoyed torturing people and impaling them, he was no more vicious than, say, the Reformation theologian John Calvin, who enjoyed torturing people by slowly roasting them on a spit while their heads were soaked with cold water to prolong the agony .… a torture that he once condemned two children to. And he isn’t any more of a monster than Guatamala’s dictator José Ríos Montt, whom Ronald Reagan admired and called “a man of great personal integrity and commitment.”