Since I found a set of scores for Haydn’s first fifty symphonies (published in Germany, and apparently withdrawn from the Mannes College of Music in New York City sometime in the 1960s), it behooves me to listen to them with score in hand. I’m not sure why the first two are not numbered, but labeled “A” and “B”, but I presume it’s because their attribution is doubtful. “B” certainly sounds like Haydn. “A” is plodding and mechanical, and could have been composed by anybody. The role of the composer in the first half of the 18th century was rather like that of a rave dj. He was expected to “spin” whatever was at hand, and much material was recycled from his own (or others’) output. Nobody kept track of who composed what, except as an after-thought. Composers where constantly fired and rehired by patrons, and hopping from one princely court to another created opportunities for purloining works, or rehashing one’s own. When necessary, baroque music could be manufactured in minutes, by assembling cookie-cutter patterns. Some baroque composers, like Giuseppe Torelli, seem to have “composed” more music than could be played end-to-end over their lifetimes. Someone used to the modern idea of a “symphony” would barely recognize these pieces as such. Later on, Haydn himself, and the young Mozart, would create the complex form of that name, by expanding the orchestration and creating structural unity beyond the mere lumping together of vaguely similar pieces. The symphonies of this period were what we would call “suites” today. But that doesn’t mean that they couldn’t be intelligent and entertaining.

Category Archives: C - LISTENING - Page 31

First-time listening for August, 2008

18962. (Franz Josef Haydn) Symphony “A” in B‑flat [1762]

18963. (Franz Josef Haydn) Symphony “B” in B‑flat [1765]

(Ruth Golden, soprano) Silent Noon: Songs of Ralph Vaughan Williams

. . . . 18964. (Ralph Vaughan Williams) House of Life, Six Songs to Poems of Dante Gabriel

. . . . . . . . Rossetti for Baritone and Piano [arr. for soprano and piano] [see original at 16063]

. . . . 18965. (Ralph Vaughan Williams) Four Last Songs to Poems of Ursula Vaughan Williams

. . . . 18966. (Ralph Vaughan Williams) “Linden Lea”, song for voice & orchestra (“In Linden Lea”;

. . . . . . . . “A Dorset Song”) [arr. voice & piano]

Read more »

Classical Composition in Early 19th Century Canada

When it comes to formal composition in Canada, before 1860, I know of nothing that was composed outside of Québec, the only part of the country with anything resembling an urban culture. There was, of course, plenty of folk fiddling, folk singing, tavern ballads, and hymn singing going on in Ontario, the West, and Atlantic Canada, but only Montréal and Québec City could support professional composers. Most of their work is unobtainable, but a sampling has been put together by l’Ensemble du Nouveau Québec under the title Anthologie de la musique historique du Québec, vol.1 ― l’époque de Julie Papineau, 1795–1862. As you might guess, it is pretty tame, provincial stuff, polkas, mazurkas and art songs of modest ambition. The most ambitious piece seems to have been Joseph Quesnel’s comic opera Lucas et Cécile (c. 1808), of which only the vocal parts survive. The two excerpts on the album display some panache, but they would have been old-fashioned in style at the time of their composition. All the works, by Quesnel, Frédéric Glackemeyer, Théodore Molt, Charles Sabatier, Ernest Gagnon, Célestin Lavigueur, and Antoine Dessane have the charm of small drawing-room compositions in a backwoods environment. They are most vigorous when they draw on folk material and local themes. However, the environment wasn’t entirely unsophisticated: Dessane made a setting of Alphonse Lamartine, at the time an avant-guarde poet. Nothing on the album, however, comes close to the impact of its best track: Antoine Gérin-Lajoie’s “Un Canadien Errant”. Strictly speaking, Gérin-Lajoie merely wrote evocative (and, at the time, politically charged) lyrics for a traditional folk song, but these lyrics are so perfect ― an exiled patriot, after the Rebellion of 1837, wanders the world, shedding tears of homesickness ― that earlier folk versions were entirely supplanted. The song has been performed by an astonishing variety of artists, ranging from Nana Mouskouri to Paul Robeson, as well as virtually every Canadian folksinger.

First-time listening for July, 2008

18926. (Niccolò Paganini) 24 Caprices for Solo Violin, Op.1

(Toronto Consort) Lasso: Chansons & Madrigals:

. . . . 18927. (Orlando di Lasso) Un jour l’ament

. . . . 18928. (Orlando di Lasso) Gallans qui par terre

. . . . 18929. (Orlando di Lasso) Ardant amour à 4

. . . . 18930. (Orlando di Lasso) Ardant amour à 5

. . . . 18931. (Orlando di Lasso) J’ay de vous voir

Read more »

YoungBird & Northern Cree Singers: Double Platinum

If you’re going to own one plains pow-wow cd, this is the one you should choose. Over the last decade, Youngbird, a powerhouse Pawnee band from Oklahoma, has loomed large in the pow-wow circuit in both the United States and Canada, with its Southern Style songs. But even more venerable are Canada’s Northern Cree Singers, from Saddle Lake, Alberta. They’ve been performing since 1980, and have 23 albums under their belts. Northern Cree are known for the sheer power of their singing, as well as well-crafted songwriting. They’ve long been the favourite among competitive dancers, since they particularly excel at “second songs”, the ones with variable rhythm and sudden, short stops, which show off a dancer’s moves. Well grounded in the Northern Style, they skillfully play off the Southern Style Youngbirds in this dynamite album recorded live at the annual Ermine Skin Band Pow-Wow, Hobbema, Alberta. Outsanding songs include Youngbird’s “Deal With It” and “Baby Dolls II”, and Northern Cree’s “Free Flyin’ ” and “Nike Town”.

If you’re going to own one plains pow-wow cd, this is the one you should choose. Over the last decade, Youngbird, a powerhouse Pawnee band from Oklahoma, has loomed large in the pow-wow circuit in both the United States and Canada, with its Southern Style songs. But even more venerable are Canada’s Northern Cree Singers, from Saddle Lake, Alberta. They’ve been performing since 1980, and have 23 albums under their belts. Northern Cree are known for the sheer power of their singing, as well as well-crafted songwriting. They’ve long been the favourite among competitive dancers, since they particularly excel at “second songs”, the ones with variable rhythm and sudden, short stops, which show off a dancer’s moves. Well grounded in the Northern Style, they skillfully play off the Southern Style Youngbirds in this dynamite album recorded live at the annual Ermine Skin Band Pow-Wow, Hobbema, Alberta. Outsanding songs include Youngbird’s “Deal With It” and “Baby Dolls II”, and Northern Cree’s “Free Flyin’ ” and “Nike Town”.

Ziryab and the Music of Andalusia

The multi-talented Paniagua family of Madrid (one of them is also an architect) have been creating, reconstructing and performing medieval Spanish music since they were teenagers. They are the acknowledged masters. All of Spain’s early musical traditions fall under their gaze, and among them is the genre known as “arabo-andalouse”, which flourished under Muslim rule in Spain, among Muslim, Christian, and Jewish musicians alike. Atrium Musicae de Madrid, one of the family’s ensembles, has produced a fine introduction to the instrumental side of the this tradition in their album Musique Arabo-Andalouse. Read more »

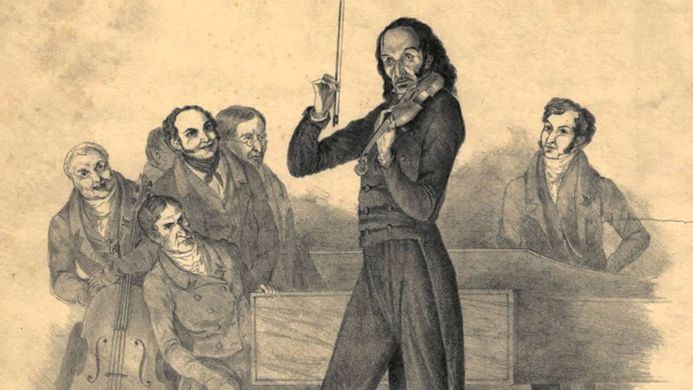

Variations and Variations of Variations — Paginini’s Rabbit-like 24th Caprice

Niccolò Paganini’s 24 Caprices for solo violin, completed around 1817, are considered among the most difficult things for a violinist to master, especially the striking final caprice, in A minor. Apart from its status as the ne plus ultra showpiece to demonstrate a violinist’s virtuosity, it’s a thumping good tune, extended into variations. Those variations have fascinated later composers, and have generated a huge number of reworkings, and fresh variations of their own device. Wikipedia lists works by 29 composers based on the last caprice. Read more »

Niccolò Paganini’s 24 Caprices for solo violin, completed around 1817, are considered among the most difficult things for a violinist to master, especially the striking final caprice, in A minor. Apart from its status as the ne plus ultra showpiece to demonstrate a violinist’s virtuosity, it’s a thumping good tune, extended into variations. Those variations have fascinated later composers, and have generated a huge number of reworkings, and fresh variations of their own device. Wikipedia lists works by 29 composers based on the last caprice. Read more »

First-time listening for June 2008

18672. (Modest Moussorgski) Boris Godunov [orch. by Rimsky-Korsakov] [opera highlights;

. . . . . d. Karajan; w. Vishnevskaya, Spiess, Maslennikov, Talvela]

18673. (Johann Sebastian Bach) Art of the Fugue, Volume 1, Groups 1–3, bwv.1080

. . . . . [orchestral version arr. by Marcel Bitsch & Claude Pascal]

(Geraint Jones, organ) Portugaliae Musica, vol. 4 — Musique Portugaise pour orgue:

. . . . 18674. (Antonio Carreira) Fantasie

. . . . 18675. (Manuel Rodrigues Coelho) Five Versets on Ave Maris Stella

. . . . 18676. (Carlos Seixas) Fugue in A Minor

Read more »

Sibelius: En Saga

Throughout my life, Sibelius has remained unchallenged as my favourite composer. As much as I might love Mozart, or Dvorak, or Vaughan Williams, and take delight in even their minor compositions, none has the place in my heart, and subconscious, that Sibelius has. The first work of the granite Finn that I ever heard was En Saga, Op.9. It has usually been considered no more than a rousing showpiece, but I think it offers some depths to explore. Read more »

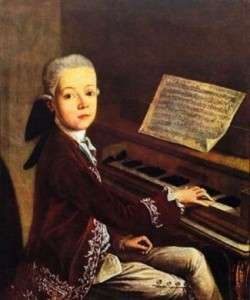

Mozart: Symphony #1 in E‑flat, K.16

Mozart composed his first symphony at the age of eight, and what’s remarkable is not only that it is a perfectly competent work, which could be played to good effect at any concert, but that it already shows many distinctly Mozartian features. It already has the sense of playful invention, of twisty-turny, peekaboo surprise that Mozart preserved in even his most serious works until the end of his life. It was composed on a visit to London, and it shows the distinct influence of Johann Christian Bach, who was also in London at the time. Influence, not mere copying, all the more remarkable because it was only his sixteenth work. It is not, as some assumed, the work of Mozart’s controlling and ambitious father, Leopold, passed off as the boy’s. While this seven minute symphony is no masterpiece, it’s impossible to listen to it without wondering how the hell this stuff could be in the mind of an eight-year-old.

Mozart composed his first symphony at the age of eight, and what’s remarkable is not only that it is a perfectly competent work, which could be played to good effect at any concert, but that it already shows many distinctly Mozartian features. It already has the sense of playful invention, of twisty-turny, peekaboo surprise that Mozart preserved in even his most serious works until the end of his life. It was composed on a visit to London, and it shows the distinct influence of Johann Christian Bach, who was also in London at the time. Influence, not mere copying, all the more remarkable because it was only his sixteenth work. It is not, as some assumed, the work of Mozart’s controlling and ambitious father, Leopold, passed off as the boy’s. While this seven minute symphony is no masterpiece, it’s impossible to listen to it without wondering how the hell this stuff could be in the mind of an eight-year-old.