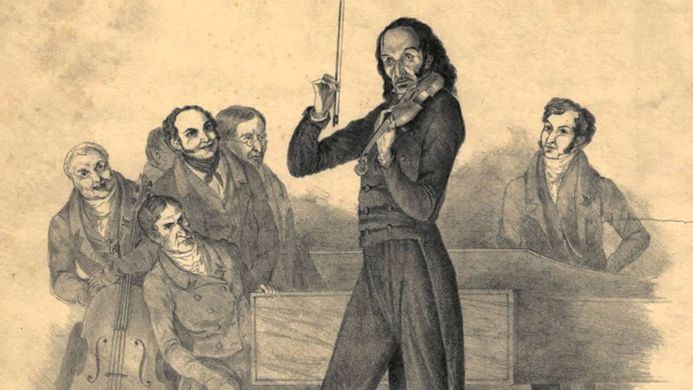

Niccolò Paganini’s 24 Caprices for solo violin, completed around 1817, are considered among the most difficult things for a violinist to master, especially the striking final caprice, in A minor. Apart from its status as the ne plus ultra showpiece to demonstrate a violinist’s virtuosity, it’s a thumping good tune, extended into variations. Those variations have fascinated later composers, and have generated a huge number of reworkings, and fresh variations of their own device. Wikipedia lists works by 29 composers based on the last caprice.

Niccolò Paganini’s 24 Caprices for solo violin, completed around 1817, are considered among the most difficult things for a violinist to master, especially the striking final caprice, in A minor. Apart from its status as the ne plus ultra showpiece to demonstrate a violinist’s virtuosity, it’s a thumping good tune, extended into variations. Those variations have fascinated later composers, and have generated a huge number of reworkings, and fresh variations of their own device. Wikipedia lists works by 29 composers based on the last caprice.

When Brahms produced his Variations for Piano on a Theme from Paganini, Op.35, both Liszt and Schumann had already worked on virtuoso piano interpretations of Paganini’s 24th. Brahms’ piece is closer to Schumann’s. He divides the the work into into two segments, Book I and Book II, each beginning with the theme, and running through variations to a bravura climax. This makes the piece sound oddly repetitive, since both sets are very similar in organization and style. Brahms, apparently, was experimenting with playing technique, and I’m told the piece is as difficult for a pianist as the original is for a violinist. But as a non-player, I’m probably missing most of its technical significance. I can see however, that he squeezes every possible emotion that you can out of the little melody, reminding you that few tunes have any fixed, inate emotional content. I have performances by Walter Rosen and Charles Klein. I play the Klein one quite often.

Karol Szymanowski’s Three caprices about Paganini themes for violin and piano was composed in 1918, roughly at the time of his love affair with the 15-year-old Russian poet Boris Kochno, and the writing of his erotic novel Efebos. The three caprices (#20, 21 and 24), in Szymanowski’s hands, are sweeter than Paganini’s originals… dripping with romantic feeling. The A minor caprice takes Paganini’s solo violin and gives it a plucky piano accompaniment that balances it well. The pizzicato passage has particularly nice interplay between the two instruments.

Sergei Rachmaninov’s Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini in A Minor, Op.43 [Рапсодия на тему ПаганиниРапсодия на тему Паганини] is probably more often played than the Paganini’s original piece. It’s a perennial “B‑side” item, usually thrown in with one of Rachmaninov’s piano concertos. Often, it’s paired with Ernst Dohnanyi’s Variations on a Nursery Theme, and that’s how I first heard it. Julius Katchen’s 1954 performance on Decca / London, which I own on the original “heavy” vinyl that weighs and feels like an old lacquer recording, is one such. I have other other performances: one in a box set of the concertos by Rafael Orozco, one by Margrit Weber, and a sparkling one by Van Cliburn, but Katchen’s remains my favourite. Rachmaninov’s treatment of the caprice is in standard variation form, but he manages to make it feel like a piano concerto, with sweeping orchestral passages, and dreamy interplay between soloist and orchestra. It was first performed in Baltimore, in 1934, with Rachmaninov at the keyboard. The heart of the piece is the lovely, slow eighteenth variation, half-way through, which is a striking “upside down” version of the theme in D‑flat. This heart-throbbing melody was ripped off for popular songs, and constantly turned up in passionate romance movies from the 30s to the 50s. Rachmaninov is said to have quipped: “This one is for my Agent.” It may be a bit much for today’s taste. But there are plenty of other entertaining, stick-in-your-memory passages in the work. I’ve always liked the abrupt, anti-climactic ending, coming after a dramatic buildup.

The under-rated Polish composer Witold Lutosławski produced yet another solo piano take on the 24th caprice. Lutosławski lived a rather hard life. A year after he was born, in 1913, his family fled to Russia to help organize Polish resistance to the German occupation, only to be trapped there by the Bolshevik revolution. At the age of five, his father and brother were executed by the Communists ― by a firing squad, a few days before their scheduled “trial”. Returning to Poland shortly after, he studied mathematics and music. He was serving in the Polish armed forces as a radio technician when the Communists and Nazis invaded and divided Poland. He was captured by German soldiers, but he escaped while being marched to prison camp, and walked 400 km back to Warsaw. At the same time, his surviving brother was captured by the Russians, and ultimately died in the Gulag. He spent the Nazi occupation of Warsaw composing and playing Resistance songs in the underground cafés that sprouted up when the Nazis banned the playing of Polish music. It was here that he composed the Variations on a Theme of Paganini. It was one of only a handful of his hundreds of early compositions that survive being incinerated during the Warsaw Uprising. After the War, he struggled for decades with Communist censorship. Many of his best works were suppressed, and were only played outside of Poland. But he continued to build an international reputation from sheer force of creativity and originality. Towards the end of his life, he became closely related with Solidarity, and lived to see Poland’s liberation. Considering the conditions under which it was composed, it’s not surprising that the Variations are far from Rachmaninov’s interpretation. Actually, they sound as if someone had been scheduled to play the Rachmaninov rhapsody, assassinated the conductor and all the orchestra, then proceeded to play a demented, frenetic parody of it, solo, under the influence of phenylcyclohexylpiperidine. In 1977, Lutosławski revised and expanded the composition into a piano concerto, which I haven’t heard.

0 Comments.