Fur Traders Descending the Missouri, c. 1845 by George Caleb Bingham. It was originally titled “French Trader, Half-breed Son” — Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York City

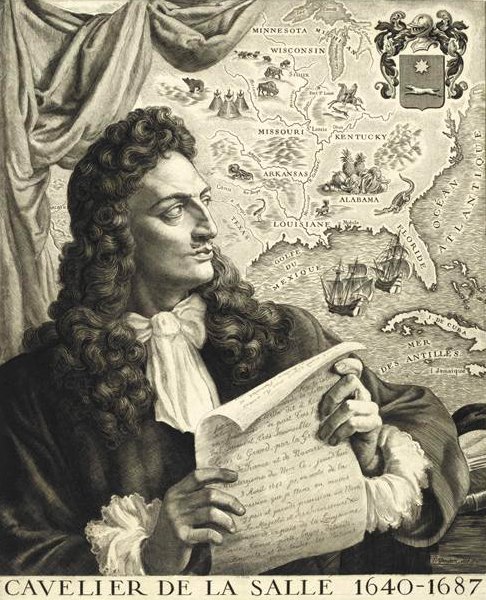

This is not, strictly speaking, a history. It’s more of a meditation on a theme. Marchand, a journalist raised in a New England French Canadian family, retraces the route traveled by Robert de La Salle in the seventeenth century. Along the way, he digs up surviving traces of French America in small towns from Wisconsin to Texas (La Salle was not a small-scale explorer) and contemplates the impact of the French empire in America. He is right, of course, to say that American historians under‑report this era. Apart from the vague impression that the Midwest was explored by General Motors cars, and a horde of mispronounced French place-names, most of it has fallen out of the American historical consciousness.

As he points out, there was a concerted effort in the Nineteenth Century to view the huge area between the Appalachians and the Rockies as a pristine wilderness, with only a few scattered Indian tribes to be pushed aside by rugged pioneer settlers. In reality, the entire region was a network of stable towns and agricultural settlements. For example, when American troops moved into Green Bay, Wisconsin , in 1816, they found a well-established town of farmers and traders. The French-speaking inhabitants were told that they would not be allowed to engage in trade unless they were American citizens. When they applied for citizenship, most were refused. Those who were allowed to stay in business could no longer engage in free trade, but only deal with the state-supported monopoly of the American Fur Company, which rapidly forced them into bankruptcy. The new regime stripped most farmers of their property, refusing to recognize land titles. Marchand only touches on this briefly, but I am familiar with the process from many historical sources, and what he hints at could be expanded into an entire book. The French-speaking society that stretched from Michigan to Montana to the mouth of the Mississippi was submerged by force and law, as well as by numbers. Those who didn’t vanish into marginal poverty, or abandon their language and religion, fled to Western Canada. There, French-speaking Métis culture shaped Canadian history in dramatic ways.

As he points out, there was a concerted effort in the Nineteenth Century to view the huge area between the Appalachians and the Rockies as a pristine wilderness, with only a few scattered Indian tribes to be pushed aside by rugged pioneer settlers. In reality, the entire region was a network of stable towns and agricultural settlements. For example, when American troops moved into Green Bay, Wisconsin , in 1816, they found a well-established town of farmers and traders. The French-speaking inhabitants were told that they would not be allowed to engage in trade unless they were American citizens. When they applied for citizenship, most were refused. Those who were allowed to stay in business could no longer engage in free trade, but only deal with the state-supported monopoly of the American Fur Company, which rapidly forced them into bankruptcy. The new regime stripped most farmers of their property, refusing to recognize land titles. Marchand only touches on this briefly, but I am familiar with the process from many historical sources, and what he hints at could be expanded into an entire book. The French-speaking society that stretched from Michigan to Montana to the mouth of the Mississippi was submerged by force and law, as well as by numbers. Those who didn’t vanish into marginal poverty, or abandon their language and religion, fled to Western Canada. There, French-speaking Métis culture shaped Canadian history in dramatic ways.

What horrified the newcomers, and made it possible to render this history invisible, was the defining difference that underlies and bifurcates North America . West of the Appalachians and north of the Great Lakes, there was a society in which people of Native, French, Scottish, and African descent intermarried, worked and lived together. Across the huge arc from the Maritime Provinces of Canada to Louisiana, politics consisted of a complex set of alliances between native tribes and habitants, in which intermarriage was not merely tolerated, but encouraged. Such marriages wer the primary method of making alliances, securing trade routes, and creating viable communities. The founder of Chicago , for example, was a Black trader born in the New World, but educated in France. Charles Langlade, who fought Braddock and Washington in 1755, was a perfect fusion of Native and French blood and culture. The Scots and Orkneymen who entered the system followed the same rules. When the British captured this vast territory [France traded away its claim to it, in exchange for a single Caribbean island], they were profoundly contemptuous of this multilingual, multiracial society, but with only a handful of troops to control it, they were forced to recognize the status quo. Native people and political institutions remained an integral part of Canadian life for at least another century (and still retain some influence to this day). Influential native families remained part of the social and political elite. The impoverishment and cultural suffocation of native communities, which is Canada’s greatest shame, largely occurred in the middle of the Twentieth Century.

At the end of the American Revolution, the British abandoned the huge territory south of the Great Lakes to its own devices. For awhile, the scattered towns continued to govern themselves by their local councils, continued to trade and farm (and party, dance, fiddle and make love with a cheerful abandon that enraged the new rulers). But eventually, a tide of settlers swept over the Appalachians , most of whom were fanatical Indian haters, and there is nothing that angers ethnic cleansers more than “miscegenation.” Ultimately, the fierce warriors of the plains would be romanticized as Noble Enemies and then as mystical symbols of new age hocus pocus. But not the métisized, francophone culture. For for more than a century there were thousands of novels, comic books, and movies produced in which sinister, dirty, French-speaking “half-breeds” slinked around twirling their mustaches, stabbing blond heroes in the back, and selling poisoned whiskey. I recently saw a 1950’s Hollywood film in which one of my own direct ancestors was portrayed somewhat like Smeagal, in Lord of the Rings. Even the Europeans, who romanticize Native American cultures to a degree of high fantasy, have never shown any interest in Métis society.

But all was not immediately suppressed. While doing research in Kansas City , I came across some curious narratives from the French period in Missouri . Some of the old francophone fur trading families of that State preserved their prosperity and local pre-eminence until just before the Civil War. Catholicism in the great “pays d’enhaut” had always been folkloric and improvisational, the Church no more able to enforce its rules than the French Crown had been able to enforce obedience. Severed from even the last vestiges of ecclesiastical influence, the mid-nineteenth century francophone bourgeois of Missouri made a fashion of being children of the Enlightenment, passing their leisure hours reading Voltaire and Jefferson (in translation). This became so notorious that a catchphrase evolved: “Dieu ne croisera jamais le Mississippi” ――”God will never cross the Mississippi ”. Clergymen fumed bitterly on the other side of the river, but it took them a generation to work up the nerve to launch a crusade. Marchand, unfortunately, didn’t hit on this vein.

That doesn’t surprise me. Marchand is fascinated by Catholicism, and his own upbringing in Catholic school in New England . I understand the phenomenon. I’ve always noticed the strange intensity of being Catholic in the United States. Canadian Catholics don’t experience it. I went to French language catholic schools, staffed with nuns and brothers. But we never had more than twenty minutes of religious instruction per week, and that was as bland and innocuous as a Unitarian sermon. Not a syllable of hellfire, and certainly no tirades against sex. Where I grew up, Catholicism meant normalcy, speaking French and playing hockey. Any excessive interest in theology was regarded as fanaticism, some kind of mental illness typical of Protestants. Reasonably demure Anglicans, and such, were okay, but anyone who talked about the Bible and sin was obviously a kook. But Catholic French Canadians in New England felt besieged, and they huddled around their parish priests and catholic schools like a circle of covered wagons. There, the faith became something quite different. Marchand’s book breathes this experience.

Another element: the book is haunted by Francis Parkman, the first popular historian of the French era in America, and the lens through which the subject has been seen ever since. Some of the best writing in the book is about Parkman’s character and influence. Other fine segments involve conversations with historical re-enactors. Marchand’s book is well-written, and extremely entertaining. It offers tid-bits and suggestions rather than a systematic history, but that is the best way to edge into an unfamiliar subject. For most Americans, this aspect of their history is a very unfamiliar subject.

0 Comments.