(Kagan 1974) Judge Dee and the Monastery Murders

(Malle 1971) Murmur of the Heart [Le souffle au coeur]

(McNaughton 1973) Monty Python’s Flying Circus: Ep.37 ― Dennis Moore

(McNaughton 1973) Monty Python’s Flying Circus: Ep.38 ― A Book at Bedtime

(Wareing 1988) Doctor Who: Ep.678 ― The Greatest Show in the Galaxy, Part 1

(Wareing 1988) Doctor Who: Ep.679 ― The Greatest Show in the Galaxy, Part 2

(Ritt 1963) Hud

(Wareing 1988) Doctor Who: Ep.680 ― The Greatest Show in the Galaxy, Part 3

(Wareing 1989) Doctor Who: Ep.681 ― The Greatest Show in the Galaxy, Part 4

(Seltzer 1986) Lucas

(Guðmundsson 2014) Ártún

(Silberling 2004) Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events

(Lourié 1953) The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms

(Elston 2013) The Other Pompeii: Life & Death in Herculaneum

(Marcus 2007) Roman Mysteries: Ep.3 ― The Pirates of Pompeii, Part 1

(Hitchcock 1936) Sabotage

(Liu & Li 2008) Justice Bao [包青天; Bāo Qīng Tiān]: Ep.1 ― Beating the Dragon Robe

Read more »

FILMS — FEBRUARY 2019

First-time listening for February 2019

25488. (Niccolò Paganini) Sonata #2 in D for Violin & Guitar “Centone di Sonate”, Op.64a

. . . . . MS112 #2

25489. (Niccolò Paganini) Grande Sonata for Violin & Guitar in A, Op.39 MS3

25490. (Niccolò Paganini) Sonata Concertata for Guitar & Violin in A, Op.61 MS2

25491. (Niccolò Paganini) Cantabile in D for Violin and Guitar, Op.17 MS109

25492. (Waka Flocka Flame) Big Homie Flocka

Read more »

READING — FEBRUARY 2019

24088. (Alberto Renzulli et al) Pantelleria Island as a Centre of Production for the Archaic ]

. . . . . Phoenician Trade in Basaltic Millstones [article]

24089. (Kenan Işik & Rifat Kuvanç) A New Part of Horse Trapping Belonging to Urartian King

. . . . . Minua from Adana Archaeology Museim and on Urišḫi-Urišḫusi-Ururda Words in

. . . . . Urartian [article]

24090. (Frida Beckman) Gilles Deleuze

Read more »

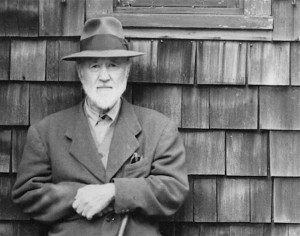

Two Wild Spirits: Heinrich and Ives

Those of us who admire a wild and irreverent spirit in music have long looked to Charles Ives (1874–1954) as our patron saint. With his multimetric chaos, his noisy brass bands, cheerful mixing of popular and classical themes, his temporal dyssynchronies and his startling flights into the infinite, he fulfilled every requirement for an eccentric genius ahead of his time. And he was profoundly, quintessentially American. But he was little known in his lifetime. The bulk of his compositions were written then tucked away, unperformed, in a New England barn while he pursued a more successful career as an insurance salesman. He also published pamphlets advocating what we would now call “direct democracy” and got into a heated argument with a young Franklin Roosevelt over his idea of promoting government bonds cheap enough for the ordinary citizen. But it was not until the 1960’s that his works were frequently played, and his name became familiar to classical musicians and listeners. Much of this change came about through the ardent advocacy of conductor Leonard Bernstein. It is possible to listen to a performance of Ives’ Symphony #4 today and experience it as “modern, avant-garde music” even though it was composed in the 1910s! (It wasn’t performed until 1965).

But fascinating as Ives is, he is not alone in the story of American music. Another composer, living a full century before him, shared many of Ives’ characteristics. Like Ives, he was self-taught, eccentric, experimental and ahead of his time. Like Ives, he wore his patriotism on his sleeve, loved loud noises and order disguised as chaos, and was drawn to transcendental themes. He died 13 years before Ives was born, and Ives probably never heard of him. Unlike Ives, however, he has found no high-profile champion. His works are played only occasionally and few people have heard them.

The man in question was Anthony Philip Heinrich. He was born in 1781, in the northernmost village of Bohemia, in what was then a predominantly German-speaking part of that land. Like Ives, he pursued a successful career as a businessman, relegating music to a hobby. But the Napoleonic wars ruined him, and he found himself penniless in Boston in 1810. He plunged into a new life enthusiastically, determined to be a wandering musician on the opening frontier. He traveled mostly on foot, living rough, through Pennsylvania, Ohio and Kentucky. This experience instilled in him a profound love of nature and an idealistic patriotism for his adopted country. Finally he settled in a log cabin in Kentucky and began to compose. America as yet had no real symphony orchestras and few trained musicians. His larger compositions could only be played in Europe. Eventually, he participated in founding the New York Philharmonic, and achieved some public success, but this quickly faded, and he died, reduced again to poverty, in 1861.

His music not only drew on American folk music and on the melodies and rhythms of Native Americans [Comanche Revel; Manitou Mysteries; The Cherokee’s Lament; Sioux Galliarde], but it was saturated with the signature element of American music: improvisation. Musicologists would no doubt classify him as his century’s most consistent practitioner of musical indeterminacy. Bird song filled his music, which often sported spectacularly grand ornithological titles: The Columbiad, or Migration of American Wild Passenger Pigeons and The Ornithological Combat of Kings. Perhaps the piece that sums him up is the vocal/orchestral suite, The Dawning of Music in Kentucky, or, the Pleasures of Harmony in the Solitudes of Nature. Nothing he composed followed the musical conventions of Europe. Altogether, I’ve heard 18 of his works, and all of them gave me pleasure, while some of them seemed to me both radical and profound. In other words, the qualities that drew me to Ives were present in Heinrich a century before.

It’s important, in this dark time for America, to remember that the nation that has sunk to the level of electing a scurrilous con-man, criminal and traitor to its highest office has in the past, over and over again, nurtured creative men and women imbued with the spirit of liberty, and will no doubt do so again. At this moment, I’m listening neither to Ives nor Heinrich, but to a country-rock album from 1968, The Wichita Train Whistle Sings. It’s by Mike Nesmith, remembered mostly as being one of television’s Monkees, but actually a man of varied talents. You can hear many elements of Heinrich and Ives bubbling through this almost, but not quite forgotten album. And they are bubbling in many works by singers, composers, garage bands, rappers, and electronic artists today. To use another Mike Nesmith album title: And the Hits Just Keep On Comin’.

FILMS – JANUARY 2019

(Melville 1950) Les Enfants Terribles

(Arkush 1979) Rock’n’Roll High School

(Crossland 2011) Murdoch Mysteries: Ep.41 ― Kommando

(Dante 1984) Gremlins

(Trelfer 2016) Dark Corners Review: (54) Gremlins: The Greatest Christmas Horror Film

. . . Retrospective

(Dante 2011) Joe Dante Introduces Gremlins for the Ciné Nasty Series

(Sawall 2010) Etruscans: Glory Before Rome

(Hough 1978) Return from Witch Mountain

(Grinter & Hawkes 1972) Blood Freak

(Trelfer 2018) Dark Corners Review: (332) Blood Freak

(Copp 2010) Inside the Milky Way

(Mancori & Mann 1964) Son of Hercules in the Land of Darkness [RiffTrax version]

(Wise 1951) The Day the Earth Stood Still

Read more »

First-time listening for January 2019

25401. (Johannes Ockeghem) Requiem [Missa pro defunctis]

25402. (Paul Oakenfold) A Lively Mind

25403. (Richard Strauss) Salome, Op.54 [complete opera; d. Sinopoli; Studer, Terfel,

. . . . . Hiestermann]

25404. (Jon Hopkins) Singularity

25405. (Aztec Camera) Walk Out to Winter: The Best of Aztec Camera

Read more »

READING – JANUARY 2019

24073. (Bruno Ernst) The Magic Mirror of M. C. Escher

24074. (Ľubomír Novák) Yaghnobi: An Example of a Language in Contact [article]

24075. (Bastiaan Star et al) Ancient DNA Reveals the Arctic Origin of Vikin Age Cod from

. . . . . Haithabu, Germany [article]

24076. (Bob Woodward) Fear ― Trump in the White House

24077. (Olivier Putelat et al) Une chasse aristocratique dans le ried centre-Alsace au premie

. . . . . moyen âge [article]

Read more »

Wednesday, January 30, 2019 — Toronto with Frosting

Attache ta tuque! Toronto doesn’t usually get much snow, compared to most of the rest of the country. Montrealers laugh at our lame, half-hearted winters. It’s position on the west end of Lake Ontario, with a ridge of highlands to its west, means that the prevailing westerlies usually drop most of their snow before they reach the city. The closest American city, Buffalo, positioned at the east end of Lake Erie, gets much more snow. But every now and then a snowstorm will be big enough to dump a hefty load on Toronto. The evening it hit was a bit grim for Torontonians, many of whom immigrated from warmer lands.

Attache ta tuque! Toronto doesn’t usually get much snow, compared to most of the rest of the country. Montrealers laugh at our lame, half-hearted winters. It’s position on the west end of Lake Ontario, with a ridge of highlands to its west, means that the prevailing westerlies usually drop most of their snow before they reach the city. The closest American city, Buffalo, positioned at the east end of Lake Erie, gets much more snow. But every now and then a snowstorm will be big enough to dump a hefty load on Toronto. The evening it hit was a bit grim for Torontonians, many of whom immigrated from warmer lands.

But look at the magic of the following sunny day:

Image of the Month

Triumph of the Virtues by Andrea Mantegna [also known as Pallas Expelling the Vices from the Garden of Virtue and as Minerva Expelling the Vices from the Garden of Virtue]

Triumph of the Virtues by Andrea Mantegna [also known as Pallas Expelling the Vices from the Garden of Virtue and as Minerva Expelling the Vices from the Garden of Virtue]

Tempera on canvas, 160 x 192 cm painted around 1500. Musée du Louvre, Paris

I had no title or artist for this painting at first. It attracted me because I couldn’t figure out, for the life of me, what the hell it was about. It took me hours to find the painter and title. I first found the Pallas version of the title. I could find no reference anywhere in Greek mythology to this particular incident, but it is clearly Pallas Athena, bearing all her symbolic paraphernalia, who is the main character. There are a plenitude of tales around Athena. However, the Minerva version of the title provides a hint: Minerva was the Roman goddess conventionally equated with Athena, and the story is probably a Roman one dating from much later. Mantegna would far more likely have culled the story from some Latin source. On the other hand, he may have simply made it up. The Renaissance played fast and loose with Classical sources, and doubtless this was painted to suit political rhetoric about “draining the swamp”. The painting literally represents a swamp enclosed in a ruined wall, with Athena driving out a horde of monsters that represent the “vices” in the conventional medieval fashion. The painting was commissioned to celebrate the coronation of Isabella d’Este as Marquise of Mantua. She was widely seen as the ideal ruler in her time, and has been revered by feminists ever since.