14612. (Michael Cunningham) A Home at the End of the World

14613. (Ian Rankin) Strip Jack

14614. (Kim Stanley Robinson) Fifty Degrees Below Zero

14615. (Dean Mahomet) The Travels of Dean Mahomet, An Eighteenth-Century Journey

. . . . . Through India [ed. with an intruction and biographical essay by Michael H. Fisher]

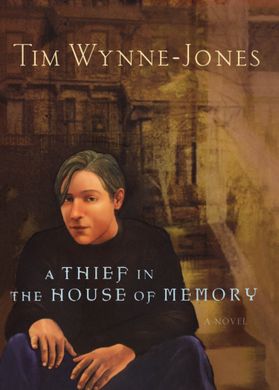

14616. (Tim Wynne-Jones) A Thief in the House of Memory

14617. (Allen F. Davis) Spearheads For Reform ― The Social Settlements and the Progressive

. . . . . Movement 1890–1914

Read more »

Category Archives: BP - Reading 2006 - Page 6

READING MARCH 2006

14616. (Tim Wynne-Jones) A Thief in the House of Memory

Tim Wynne-Jones lives in the picturesque town of Perth, Ontario, about an hour’s drive from Ottawa. A small-town Canadian sensibility is the framework for this novel, written for teenagers, but it is not the nostalgia of Leacock’s Sunshine Sketeches by a longshot. It is closer to the haunted past and stiffled hopes in Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg Ohio. A Thief in the House of Mermory is beautifully written. The prose style is exquisite, full of invention and wordplay, and the dialog feels true. Despite the disturbing and depressing subject matter, the book is not just the product of facile cynicism. It is about confronting the past and dealing with it, and the decision to know the truth even if it brings you pain. Wynne-Jones is clearly writing intelligent, moving, and technically superb fiction for the “young adult” market, and the Toronto publisher Douglas & McIntyre is not putting obstacles in his way. I will eagerly investigate his other books, and the publisher.

Tim Wynne-Jones lives in the picturesque town of Perth, Ontario, about an hour’s drive from Ottawa. A small-town Canadian sensibility is the framework for this novel, written for teenagers, but it is not the nostalgia of Leacock’s Sunshine Sketeches by a longshot. It is closer to the haunted past and stiffled hopes in Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg Ohio. A Thief in the House of Mermory is beautifully written. The prose style is exquisite, full of invention and wordplay, and the dialog feels true. Despite the disturbing and depressing subject matter, the book is not just the product of facile cynicism. It is about confronting the past and dealing with it, and the decision to know the truth even if it brings you pain. Wynne-Jones is clearly writing intelligent, moving, and technically superb fiction for the “young adult” market, and the Toronto publisher Douglas & McIntyre is not putting obstacles in his way. I will eagerly investigate his other books, and the publisher.

14615. (Dean Mahomet) The Travels of Dean Mahomet, An Eighteenth-Century Journey Through India [ed. with an intruction and biographical essay by Michael H. Fisher]

This is a fascinating document. Dean Mahomet came from a modestly successful Muslim family in India in the 18th Century, just at the period when the East India Company was absorbing and taking over the crumbling Mughal Empire. At the age of eleven, he became the friend and confidant of a teenage British officer, and for the next sixteen years they advanced together in that curious entity, the Indian Army. Together, they saw action at the siege of Gwalior, the Great Mutiny, and other key events. When a sudden (though apparently undeserved) disgrace ended his friend’s career, D.M. chose to accompany him to his native Ireland. He seems to have been personally charming, and was thoroughly self-educated in the literary culture of England.

This is a fascinating document. Dean Mahomet came from a modestly successful Muslim family in India in the 18th Century, just at the period when the East India Company was absorbing and taking over the crumbling Mughal Empire. At the age of eleven, he became the friend and confidant of a teenage British officer, and for the next sixteen years they advanced together in that curious entity, the Indian Army. Together, they saw action at the siege of Gwalior, the Great Mutiny, and other key events. When a sudden (though apparently undeserved) disgrace ended his friend’s career, D.M. chose to accompany him to his native Ireland. He seems to have been personally charming, and was thoroughly self-educated in the literary culture of England.

In Cork, Ireland, he married into the local Anglo-Irish gentry. He wrote and published his book, which is an account of his military career, with an emphasis on describing the sights and customs of the regions in Northern India that he traversed. It must be remembered that, for him, most places in India were just as “foreign” as Belgium or Denmark would be to an Englishman. The description of a famine is particularly engrossing. Read more »

14614. (Kim Stanley Robinson) Fifty Degrees Below

Kim Stanley Robinson is always readable, though the narrative often stops dead so that the reader can be supplied with large quantities of scientific, historical, or political information. It’s to Robinson’s credit that he can pull off these disquisitions without losing the reader. But it makes his novels a bit emotionally cool. This is Robinson’s Global Warming novel. It begins, interestingly, with the city of Washington ravaged by a devastating flood. The description of the clumsy and inadequate response is wonderfully prescient — the book was released only months before the New Orleans flood, and must have been written in 2004. The book didn’t strike terror into my heart, as was intended, since the science fictional premise is that the United States is suddenly forced to have Canada’s climate. I’ve been outdoors in fifty-below zero weather numerous times, and, while a bracing experience, the phrase “fifty below” doesn’t have quite the same scare value for me that it does for a Californian.

Kim Stanley Robinson is always readable, though the narrative often stops dead so that the reader can be supplied with large quantities of scientific, historical, or political information. It’s to Robinson’s credit that he can pull off these disquisitions without losing the reader. But it makes his novels a bit emotionally cool. This is Robinson’s Global Warming novel. It begins, interestingly, with the city of Washington ravaged by a devastating flood. The description of the clumsy and inadequate response is wonderfully prescient — the book was released only months before the New Orleans flood, and must have been written in 2004. The book didn’t strike terror into my heart, as was intended, since the science fictional premise is that the United States is suddenly forced to have Canada’s climate. I’ve been outdoors in fifty-below zero weather numerous times, and, while a bracing experience, the phrase “fifty below” doesn’t have quite the same scare value for me that it does for a Californian.

14612. (Michael Cunningham) At Home at the End of the World

This novel pleased me. It’s well-written, the characters come alive, and the author doesn’t pussy-foot. Cunningham takes three characters from childhood, bringing them up to youthful adulthood. They end up forming a precarious family and raise a shild. Nothing very extraordinary happens. But it is all done with great skill. The book is grown-up. As I turned the pages, I was reminded of my protracted struggle with the current situation in Science Fiction publishing. I grew up with Science Fiction, and I would rather write in that genre than write the sort of thing that Michael Cunningham does. Read more »

READING FEBRUARY 2006

14594. (Gavin Menzies) 1421, the Year China Discovered the World

14595. (Louise Levathes) When China Ruled the Seas

14596. (Birgit & Peter Sawyer) Medieval Scandinavia From Converson to Reformation,

. . . . . circa 800‑1500

14597. (Ellis Peters) The Summer of the Danes Read more »

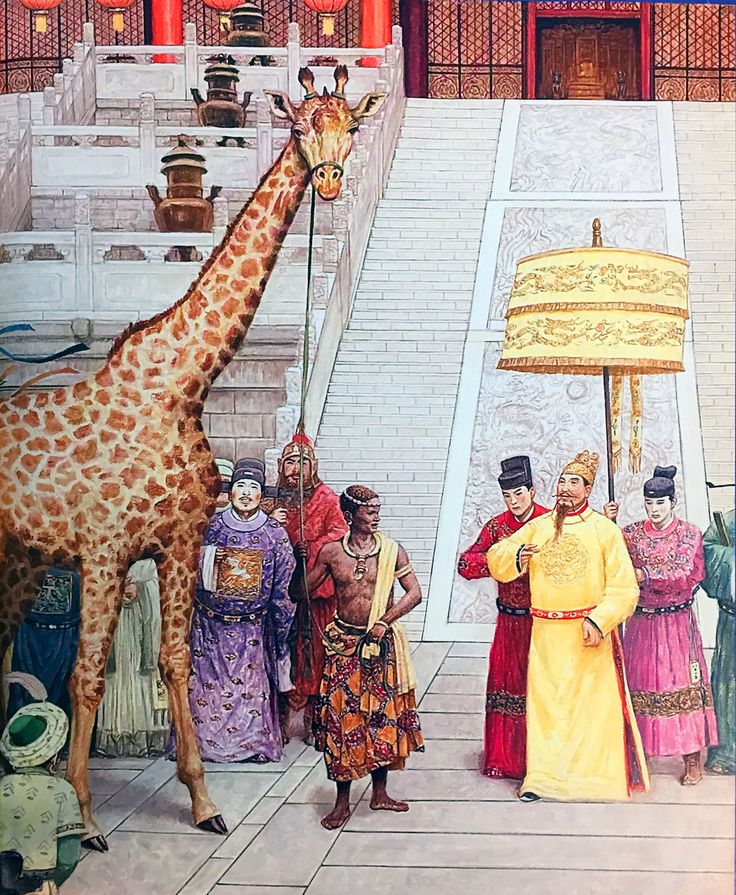

14594. (Gavin Menzies) 1421, the Year China Discovered the World

Farley Mowat engaged in some unrestrained speculation with his “Alban” prehistoric explorers. Now, Gavin Menzies goes absolutely wild with speculation in his “reconstruction” of a gigantic global exploration by the Chinese admiral Zheng He in the year 1421.

Farley Mowat engaged in some unrestrained speculation with his “Alban” prehistoric explorers. Now, Gavin Menzies goes absolutely wild with speculation in his “reconstruction” of a gigantic global exploration by the Chinese admiral Zheng He in the year 1421.

It is well known that a large Chinese Imperial fleet, under the direction of Zheng He (or Heng Ho), the eunuch aide-de-camp of the early Ming emperor Zhu Di, undertook seven long voyages that combined trade, diplomatic and exploratory motives. Chinese trade and exploration of the East African coast is well accepted by historians. Zheng He’s voyages are well documented by his secretary, Ma Huan, whose chronicling of some of the voyages was widely printed and distributed, and there are collateral accounts by Fei Xin and Gong Zhen, both officers on some of the voyages. There is also plenty of corroboration in Ming dynasty public records. Zheng He’s celebrity was such that plays were being performed about him while the voyages were still going, and a century and a half later, an immensely popular historical novel, Journey of the Three-Jeweled Eunuch to the Western Oceans by Luo Maodeng, retold the story with embellishments. Read more »

READING JANUARY 2006

(Stephen Leacock) Behind the Beyond

. . . . 14545. (Donald Cameron) Introduction [preface]

. . . . 14546. (Stephen Leacock) Behind the Beyond, A Modern Problem Play [article]

. . . . 14547. (Stephen Leacock) With the Photographer [article]

. . . . 14548. (Stephen Leacock) The Dentist and the Gas [article]

. . . . 14549. (Stephen Leacock) My Lost Opportunities [article] Read more »

14591. (Farley Mowat) The Farfarers

This is Farley Mowat’s odd book about a possible pre-viking European presence in the Canadian Arctic.

Mowat is very careful to warn the reader that he is engaging in a kind of speculative archaeology. He even intersperses the text with little passages of adventure fiction. But it is also clear that he has convinced himself pretty thoroughly that his speculations correspond to what actually happened. And the result is, of course, one of those books where a chapter begins with the assertion that something might have happened , which by the end of the chapter has been gradually transformed into what certainly did happen , and then becomes the premise for the next chapter, which begins with if that happened, then this might have happened , and so on. Gradually, a huge sequence of suppositions begins to have the appearance of a framework of solid evidence, when it is most clearly not.

What he begins with is something which is verifiably true. The eastern Arctic of Canada is littered with odd ruins and megalithic structures that can not be easily attributed to the Inuit, or to the earlier Dorset or Thule cultures. Nor do they appear to be built by the Norse. They are definitely very old. The most interesting concentrations are on the western shore of Ungava bay, and in a bay immediately south of the spectacular Torngat range, in Labrador. Read more »

14588. (Harry Mulisch) The Discovery of Heaven [= De ontdekking van de Hemel, tr. from Dutch by Paul Vincent]

This is a reasonably interesting novel, though not economically written. It’s a sprawling omnibus of digressions, combining fantasy, mysticism, politics and a kind of Jules et Jim triangle romance. Mulisch is intelligent, learned, and absolutely saturated with conventional systems and intellectual orthodoxy. There is a lot of thought in this book, but not a particle of original thought. This is, unfortunately, supposed to be the great masterpiece of modern Dutch literature. Well, the Dutch have blessed the world with wonderful painting and architecture, and their trance djs are superb, but literature just doesn’t seem to be their strong point. Nevertheless, I might recommend it for a lazy afternoon’s reading. The interaction of the characters is sometimes interesting.