This fascinating book dates from 1989, when the Gay Rights movement was in confusion and transformation. The authors, who came from a background of neuropsychology and mathematics (Kirk), public relations and advertising (Madsen), where among the minority of gay intellectuals who felt that the stagnation that their cause had suffered during the resurgence of religious fundamentalism in the U.S. owed more to flaws and failures in the gay community than to the strength of its enemies. They felt that there was a clearly trodden path by which despised minorities had historically won a place in American society, and that their generation of gay activists had failed to follow that path, and become their own worst enemies. In retrospect, much of their argument now seems common sense. Considerable progress has been made in this area (though much more in Canada than in the United States), and it has been made largely by the growth of a new mindset among gays. Kirk and Madsen presaged this new mindset. Read more »

Category Archives: B - READING - Page 37

15132. (Marshall Kirk & Hunter Madsen) After the Ball: How America Will Conquer Its Fear and Hatred of Gays in the ’90s

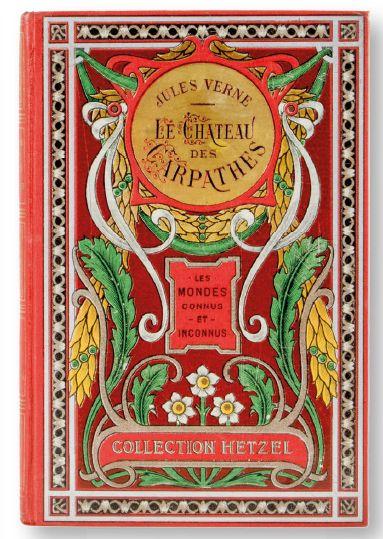

15131. (Jules Verne) Le château des Carpathes

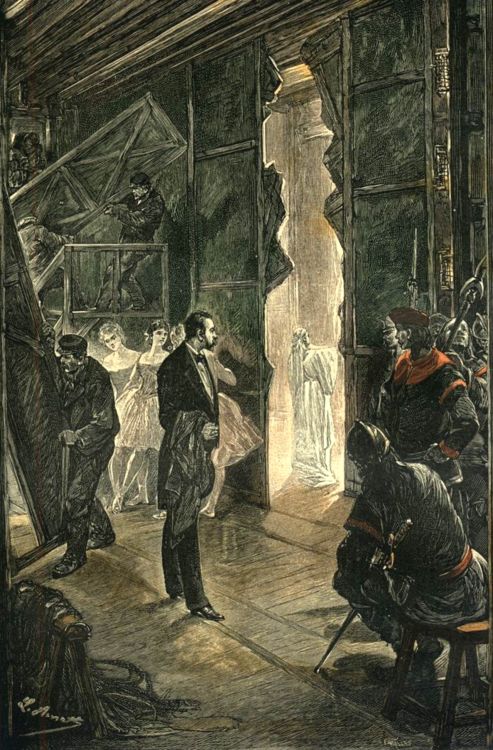

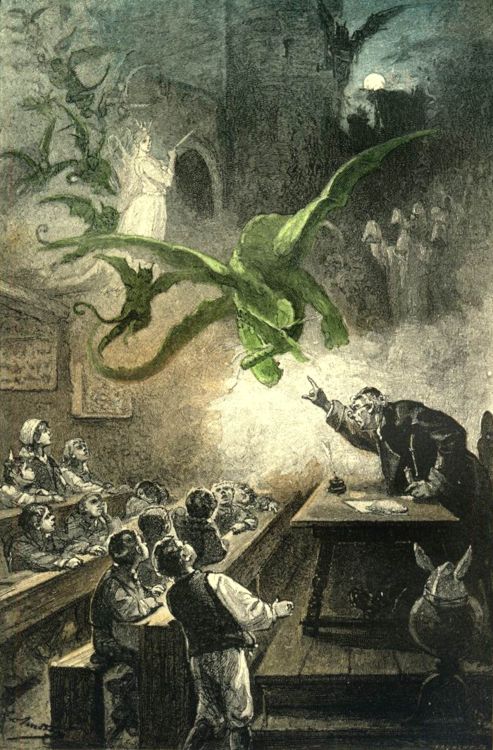

This is a minor work by Jules Verne, but it entertained me greatly because it’s set in Transylvania, where I have just been hiking and touring. In fact, the main action takes place precisely in the place I was exploring on foot with my friend Isaac White ― the mountains of Hunedoara. Here he places a mysterious castle, and a mad scientist who has invented television. The book was written in 1893, and counts as one of the first fictional speculations on this idea that did not involve the supernatural. However, the story is pedestrian by Verne’s standards, and consists mostly of dissertations on the flora, fauna, geology, and history of the region, in the style that Verne fell back on when he wrote on autopilot.

This is a minor work by Jules Verne, but it entertained me greatly because it’s set in Transylvania, where I have just been hiking and touring. In fact, the main action takes place precisely in the place I was exploring on foot with my friend Isaac White ― the mountains of Hunedoara. Here he places a mysterious castle, and a mad scientist who has invented television. The book was written in 1893, and counts as one of the first fictional speculations on this idea that did not involve the supernatural. However, the story is pedestrian by Verne’s standards, and consists mostly of dissertations on the flora, fauna, geology, and history of the region, in the style that Verne fell back on when he wrote on autopilot.

illustrations by

Léon Benett

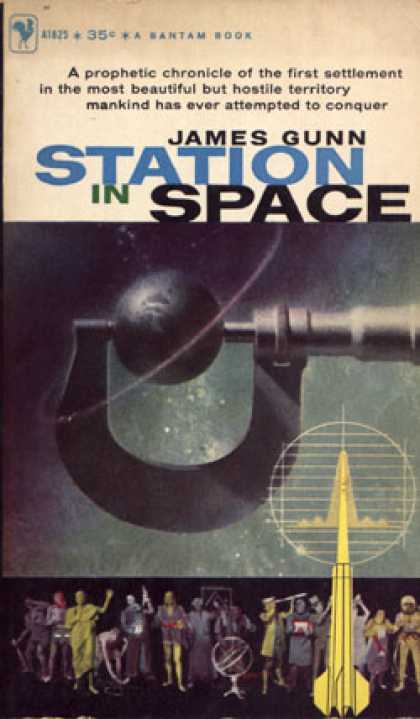

(James E. Gunn) Station In Space

James Gunn was writing “hard science fiction” in the 1950’s, and was in some ways the precursor of people like Ben Bova and Larry Niven. The connected stories in this book are Gunn’s attempt to envision the construction of an orbiting space station, at a time when “serious” scientists still dismissed talk of space exploration as mere fantasy. Unlike many who had written stories in which eccentric scientists built space ships in their back yards, Gunn understood that such a project would require engineering and financing on a mammoth scale, and would involve political complexities. The stories are quaint, now, but will interest anyone who reads fiction with a historical perspective.

James Gunn was writing “hard science fiction” in the 1950’s, and was in some ways the precursor of people like Ben Bova and Larry Niven. The connected stories in this book are Gunn’s attempt to envision the construction of an orbiting space station, at a time when “serious” scientists still dismissed talk of space exploration as mere fantasy. Unlike many who had written stories in which eccentric scientists built space ships in their back yards, Gunn understood that such a project would require engineering and financing on a mammoth scale, and would involve political complexities. The stories are quaint, now, but will interest anyone who reads fiction with a historical perspective.

contents:

15119. (James E. Gunn) The Cave of Night [story]

15120. (James E. Gunn) Hoax [story]

15121. (James E. Gunn) The Big Wheel [story]

15122. (James E. Gunn) Powder Keg [story]

15123. (James E. Gunn) Space Is a Lonely Place [story]

15105. (Joseph-Charles Taché) Des provinces de l’Amérique du Nord et d’une union fédérale

The Separatist movement in Québec has managed to train an entire generation into thinking that Québec’s entry into Confederation was some sort of conspiratorial swindle, but the truth of the matter is that the very idea of Confederation originated in that province, and was largely promoted by French Canadian intellectuals seeking a strategy to defend and preserve their culture. The fact is that the principle threat to the language and distinct culture of French Canada was, in the 19th century, the possibility of the absorption of Canada by the United States. The first detailed and systematic proposal for a Canadian Confederation was this treatise by Taché, published in 1858. Taché was a doctor practicing in the lumber camps of the wilder parts of the Gaspé peninsula, where he became enamored with aboriginal culture, and collected folklore. His later career in journalism focused on the development of a strong and distinct French Canadian literature, preferably one that “ventured into the unknown.” As a matter of principle, he refused to wear any article of clothing not manufactured in Canada. He was, in effect, a romantic nationalist of the 19th century mode. Not altogether progressive, he preferred a timid reform of the archaic system of seigniorial land tenure, rather than the complete abolition that the public clamored for. This lost him support in his political career, though in other issues he remained highly popular. Read more »

READING – JUNE 2007

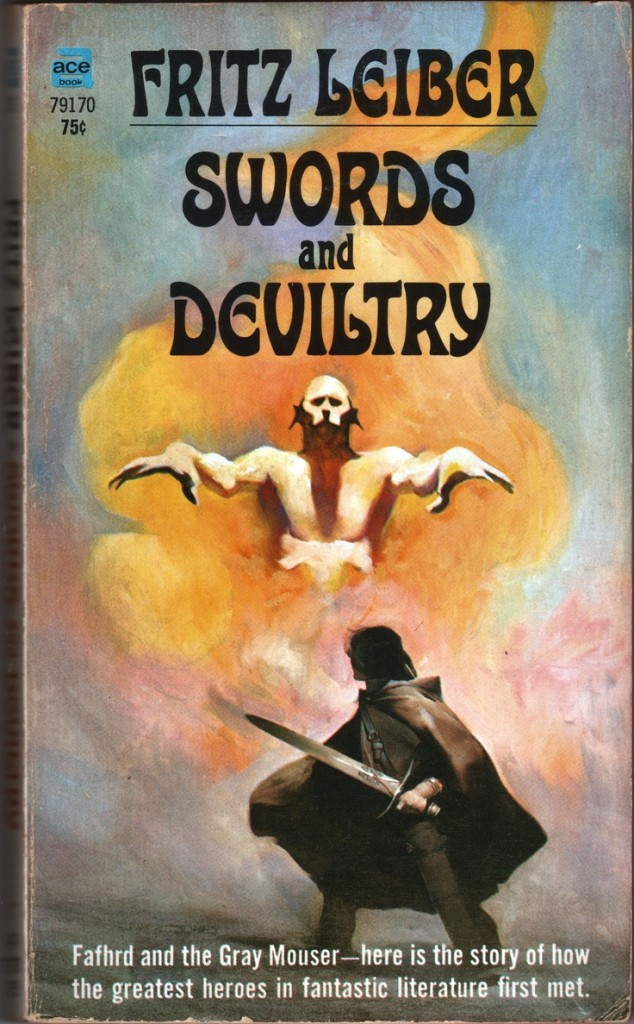

(Fritz Leiber) Swords and Deviltry:

. . . . 15064. (Fritz Leiber) Introduction [preface]

. . . . 15065. (Fritz Leiber) Induction [story]

. . . . 15066. (Fritz Leiber) The Snow Women [story]

. . . . 15067. (Fritz Leiber) The Unholy Grail [story]

. . . . 15068. [2] (Fritz Leiber) Ill Met In Lankhmar [story]

15069. (Robert Benchley) Happy Childhood Tales [story] Read more »

15087. (Philip Zimbardo) The Lucifer Effect ― Understanding How Good People Turn Evil

Psychologist Philip Zimbardo devised and supervised one of the most famous experiments in social dynamics, the Stanford Prison Experiment. A group of college students were cast in the roles of “guards” and “inmates” in a mock prison. Intense abuses spontaneously developed, as the “guards” quickly evolved into sadistic monsters.

But this book is not just about his landmark experiment. Zimbardo was asked to testify as an expert witness in abuse of power and the psychology of turture during the investigations of the abuses in Abu Ghraib. It was this experience that prompted him to put together a comprehensive study of all the social psychology experiments, such as Milgram Experiment, which led up to his own work, and to blend it with a detailed analysis of Abu Ghraib. Read more »

(Fritz Leiber) Swords and Deviltry

God only knows how much “sword & sorcery” type fantasy is in print. But if, like me, you find very little of it appealing to either your imagination or your intelligence, then it’s nice to be reminded that some of the classics of the field remain fresh and satisfying. Few people can claim to have written better heroic fantasy than Fritz Leiber, whose Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser stories where written with wit and sophistication. He wrote with an adult sensibility, avoiding the prissiness and infantile repression that were common in the field. These stories, which were written over several decades, were collected in several volumes, of which this is the first. The last story, “Ill Met In Lankhmar”, is just about as good as a story about a muscular barbarian hero can get. Read more »

God only knows how much “sword & sorcery” type fantasy is in print. But if, like me, you find very little of it appealing to either your imagination or your intelligence, then it’s nice to be reminded that some of the classics of the field remain fresh and satisfying. Few people can claim to have written better heroic fantasy than Fritz Leiber, whose Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser stories where written with wit and sophistication. He wrote with an adult sensibility, avoiding the prissiness and infantile repression that were common in the field. These stories, which were written over several decades, were collected in several volumes, of which this is the first. The last story, “Ill Met In Lankhmar”, is just about as good as a story about a muscular barbarian hero can get. Read more »

READING – MAY 2007

15055. (Captain Marryat) The Settlers In Canada

15056. (P. G. Wodehouse) Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen

15057. (Agatha Christie) Three-Act Tragedy

15058. [6] (Edgar Pangborn) A Mirror for Observers

15059. (P. G. Wodehouse) The Inimitable Jeeves

15060. (Gyula Kristó) Early Transylvania, 895–13245

15062. (Jan Kulich) Kutná Hora, St. Barbara Cathedral and the Town

15063. (P. G. Wodehouse) Jeeves in the Offing

READING – APRIL 2007

15036. (Simon Schama) Rough Crossings ― Britain, the Slaves, and the American Revolution

15037. (Timothy Finn) Three Men {Not} in a Boat and Most of the Time Without a Dog

15038. (Don Aker) Stranger At Bay

15039. (George Santayana) Classic Liberty [article]

15040. (Tony Karon) Condi’s Free Ride: The Fantasy of American Diplomacy in the Middle

. . . . . East [article]

15041. (Glen Greenwald) Your Modern-day Republican Party [article]

15042. (Neil McKenna) The Secret Life of Oscar Wilde

Read more »

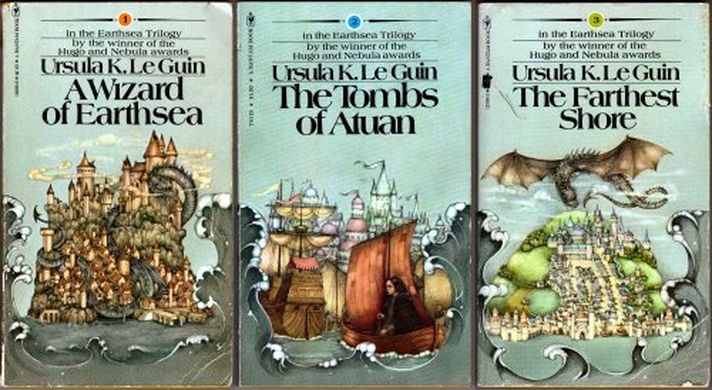

Ursula K.LeGuin’s Earthsea books

I decided to read through the well-known series of juvenile fantasy that I never got around to reading. Lequin’s Earthsea books are widely admired. Certainly, the first volume starts off well. The fantasy world is well-constructed, with the geography meticulously thought out. Things move along quickly, because the prose style is very lean, with only the odd bit of concrete, sensory description thrown in judiciously. I would never right that “thin” a prose myself, but LeGuin seems to be able to get away with it. The main character, Ged, is a bit of a stick of wood. I found myself picturing him as Wesley Crusher dressed up in a wizard cloak. The dragon is the best character. The second book was unfocused, the third was a good read, but recycled the themes of the first, and the fourth, written a full twenty-two years after the first, was downright boring. There was a fifth, published in 2001, which I haven’t even looked for. I would have to say that only the first volume really inspired me, and that it supplied all that I needed from the series.

I decided to read through the well-known series of juvenile fantasy that I never got around to reading. Lequin’s Earthsea books are widely admired. Certainly, the first volume starts off well. The fantasy world is well-constructed, with the geography meticulously thought out. Things move along quickly, because the prose style is very lean, with only the odd bit of concrete, sensory description thrown in judiciously. I would never right that “thin” a prose myself, but LeGuin seems to be able to get away with it. The main character, Ged, is a bit of a stick of wood. I found myself picturing him as Wesley Crusher dressed up in a wizard cloak. The dragon is the best character. The second book was unfocused, the third was a good read, but recycled the themes of the first, and the fourth, written a full twenty-two years after the first, was downright boring. There was a fifth, published in 2001, which I haven’t even looked for. I would have to say that only the first volume really inspired me, and that it supplied all that I needed from the series.