14835. (Kenneth Hsien-yung Pai [Bái Xiānyǒng] ) Crystal Boys

14836. (Alfred J. Andrea) The Crusades in the Context of World History [article]

14837. (Iota Sykka) Unique Mycenaean Suit of Armor Due for Conservation [article]

14838. (Cesare, marchese di Beccaria-Bonesana) Des délits et des peines, traduction nouvelle

. . . . . et seule complète, accompagnée de notes historiques et critiques sur la législation

. . . . . criminelle ancienne et moderne, le secret, les agens provocateurs, etc.

14839. (François-Marie Arouet, dit Voltaire) Commentaire sur le livre Des délits et des

. . . . . peines de César de Beccaria

14840. (Joseph Michel Antoine Servan) Discours sur La justice criminelle, 1766, avec des notes

Read more »

Category Archives: B - READING - Page 39

READING – NOVEMBER 2006

14851. (Stanley Elkin) The Living End

Stanley Elkin was never exactly popular, but his dark tragi-comic fantasies appealed to an off-beat minority. The Living End, written in 1979, is still very readable, though hard to describe. It manages to include a journey through heaven and hell where there really are pearly gates, and you are really damned to eternal torment because you took the Lord’s name in vein, and a war between Minneapolis and St. Paul [“Let me tell you something, gentlemen. A St. Paul baby ain’t got no business on the point of a Minneapolis bayonet.”] Elkin’s twisted humour is not for everyone. Does anyone read him, nowadays? So many interesting and unique writers end up lost in the shuffle of time.

14843. (Nicholas Ostler) Empires of the Word, A Language History of the World

The title of this book is a little misleading. Only a few of the world’s thousands of languages are even mentioned in it. What the book is really about is the successful Lingua francas, the languages that achieved widespread usage through conquest, trade, or cultural prestige. So his attention focuses on Akkadian, Aramaic, Greek, Sanskrit, Chinese, Malay, Latin, Portuguese, Spanish, French, Russian, and English, each of which expanded far beyond their ethnic puddles. On this topic, it is a fine introduction to the general reader. Anyone who studies world history should read it. Ostler is at his best when talking about Sanskrit, which he obviously is particularly attracted to. His explanation of why Sanskrit is so rich in puns, for example, is very interesting. Elsewhere, I’ve written about the sophistication of the Sanskrit grammarian Panini. Ostler gives a clear explanation of why his work is so remarkable. Ostler is not, like many people who have written on the topic, unthinkingly triumphant about the future dominance of English as a world language. In the book, he shows exactly how a “universal” language can evaporate its own utility and popularity. Personally, I suspect that English will retain its role as the “Latin” of this century, and that this will in no way inhibit the renaissance of local vernaculars and new regional players. We are entering a new age of linguistic wealth.

14835. (Kenneth Hsien-yung Pai [Bái Xiānyǒng] ) Crystal Boys

Bai Xianyong is said to be the best stylist among today’s Taiwanese writers, and among the best writing in Chinese today. This is not something I’m in a position to judge. This novel translates well, partly because the subject matter, the subculture of gay hustlers in Taipei, is easily compared to similar settings in Europe or North America. Chinese society, for most of the thousands of years of its history, was not infected by the barbaric homophobia that obsessed Christian Europe. Unfortunately, European cultural norms, and of course the vicious gay-hatred of Communism on the mainland, have had their influence, and today the gay subculture of Taiwan occupies much the same social position that it does in America. Bai’s hustler characters could as easily be found in Toronto’s Church and Wellesley village, or in West Hollywood. The perfume of Chinese imagery, of jade and plum blossoms and so on, makes it seem a bit different. So do the numerous references to contemporary Chinese pop culture. Is it a good novel? Yes. The characters seem real, and you care about what happens to them. I recommend it.

READING – OCTOBER 2006

14797. (Akdi Rostagno, Julian Beck & Judith Malina) We, The Living Theatre

14798. (Will Bunch) The Media Is Helping Bush Scare the Populace [article]

14798. (Lisa Finnegan) No Questions Asked – News Coverage Since 9/11 [introduction and chapter

. . . . . outlines of book to be published in December, 2006]

14799. (Robert Bowring) China’s growing might and the spirit of Zheng He [article]

14800. (Jon George) Zootsuit Black Read more »

Friday, October27, 2006 — Tread Softly

I’ve never been a big fan of William Butler Yeats — from that period, Gerard Manley Hopkins is more to my taste — but this short poem pleases me. If you have ever been quietly, unselfishly and vulnerably in love with another person, you will know that he has captured the sensation exactly.

He wishes for the cloths of heaven

Had I the heavens’ embroidered cloths,

Enwrought with golden and silver light,

The blue and the dim and the dark cloths

Of night and light and the half-light,

I would spread the cloths under your feet:

But I, being poor, have only my dreams;

I have spread my dreams under your feet;

Tread softly, because you tread on my dreams.

No tedious cycles of history, sloughing beasts, or celtic blarney, here. Apparently, Yeats occasionally stepped off the cosmic merry-go-round to feel something in an ordinary way. Love is not a topic that poets of the twentieth century handled well. Too plebian, I guess. And it takes courage.

[Addendum: A reader informs me that Yeat’s poem is actually religious in nature, and not about love at all. He explained the references in the phrasing that identify it as actually being about contrition, repentance and “hidden evil”. *sigh* Why are poets attracted to such tedious nonsense? I guess it was to good to be true to think a twentieth century poet would be willing to address an issue that really matters, and requires real thought, rather than the endless re-arrangement of inane religious twaddle.]

14801. (Stephen Fry) Moab Is My Washpot

Stephen Fry has the kind of effortless talent that makes me envious. He is a brilliant actor and comedian (Blackadder; Jeeves and Wooser; A Bit of Fry and Laurie), and fine writer of fiction, non-fiction, screenplays and plays (I’m in the middle of his novel Making History). Naturally, such a person would be expected to write an interesting biography. But I was unprepared for the extreme honesty and sparkling wit of this book. It’s devoted entirely to his childhood and teenage years, always the most interesting parts of an autobiography, if it is honest. His description of his first experience of feeling love is among the finest I’ve read. His self-evaluations strike me as spot-on, his confessions to misdeeds are not twisted into self-glamorizing. The book is absolutely engrossing. For the aspects of human culture that offend him, he reserves a special, eloquent anger: Read more »

14800. (Jon George) Zootsuit Black

This is Jon George’s second novel, which I read eagerly after being very pleased by Faces of Mist and Flame. This one is much more complicated, juggling several characters and situations. The plot involves a sudden alteration in the fabric of reality, experienced by the whole earth, a character trying to pin down the nature of psychic abilities, and characters flashing on events in the past. Among those events is the assassination of SS–Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich, who was perhaps the principal architect of the Holocaust. This fascinated me. I not only made a study of the Wansee Conference, where Heydrich consolidated his plans, but a friend showed me the exact spot in the Prague suburb of Kobylisy where he was shot by Czech partisans. I will recommend this novel, especially to anyone who has already read Faces of Mist and Flame, with the caveat that its narrative complexity requires more attentive reading.

READING – SEPTEMBER 2006

14749. (Cory Doctorow) Someone Comes to Town, Someone Leaves Town

14750. (Joseph Kage) Chapitre Premier: Esquisses de la vie Canadienne sous Le Régime Français

14751. (David G. Hubbard) The Skyjacker, His Flights of Fancy

(Bernard DeVoto) Mark Twain At Work:

. . . . 14752. (Bernard DeVoto) The Phantasy of Boyhood: Tom Sawyer [article]

. . . . 14753. (Mark Twain) “Boy’s Manuscript” [fragment anticipating Tom Sawyer]

. . . . 14754. (Bernard DeVoto) Noon and the Dark: Huckleberry Finn [article]

. . . . 14755. (Bernard DeVoto) The Symbols of Despair [article]

14756. (Robert Graves) I, Claudius

Read more »

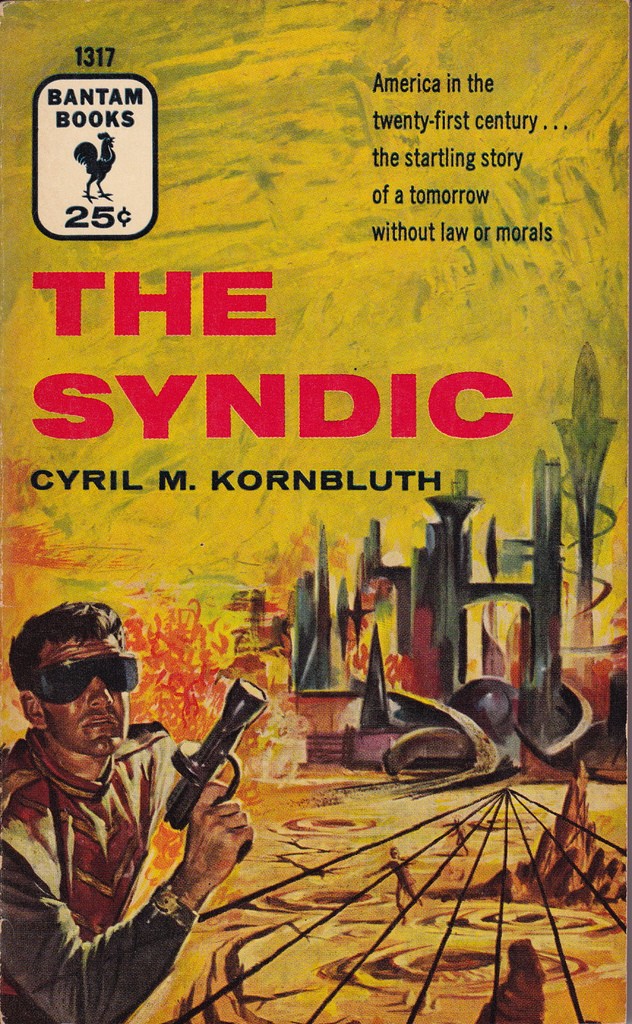

14777. (Cyril M. Kornbluth) The Syndic

There was something absolutely wonderful about the kind of science fiction that was published in the American SF magazines in the 1950’s. While the “mainstream” fiction writers struggled to obey increasingly rigid notions of “realism” and the short story virtually disappeared as an art form in the literary world, Science Fiction writers flourished in their small ghetto, free to let their imaginations roam, and free to satirize society with infinite jest. That wonderful creative cauldron gave us Theodore Sturgeon, Philip K. Dick, Avram Davidson, Edgar Pangborn, William Tenn, Alfred Bester, and many, many more. These were among the finest writers America ever produced. There was one writer that almost all these men looked up to and admired, and that was Cyril M. Kornbluth. Sadly, his career ended with premature death in 1958, after only seven years of writing. But in those seven years he produced several masterpieces in collaboration with Fredrik Pohl —such as the brilliant satire of advertising, The Space Merchants, and the remarkably prescient Gladiator-at-Law. He also produced several fine novels on his own, much more biting (perhaps because Pohl’s mellower personality influenced the collaborations), as well as a plethora of brilliant short stories. ‘The Little Black Bag’ and ‘The Marching Morons’ are perfect examples of his superb artistry.

There was something absolutely wonderful about the kind of science fiction that was published in the American SF magazines in the 1950’s. While the “mainstream” fiction writers struggled to obey increasingly rigid notions of “realism” and the short story virtually disappeared as an art form in the literary world, Science Fiction writers flourished in their small ghetto, free to let their imaginations roam, and free to satirize society with infinite jest. That wonderful creative cauldron gave us Theodore Sturgeon, Philip K. Dick, Avram Davidson, Edgar Pangborn, William Tenn, Alfred Bester, and many, many more. These were among the finest writers America ever produced. There was one writer that almost all these men looked up to and admired, and that was Cyril M. Kornbluth. Sadly, his career ended with premature death in 1958, after only seven years of writing. But in those seven years he produced several masterpieces in collaboration with Fredrik Pohl —such as the brilliant satire of advertising, The Space Merchants, and the remarkably prescient Gladiator-at-Law. He also produced several fine novels on his own, much more biting (perhaps because Pohl’s mellower personality influenced the collaborations), as well as a plethora of brilliant short stories. ‘The Little Black Bag’ and ‘The Marching Morons’ are perfect examples of his superb artistry.

A fine introduction to Kornbluth’s work would be this novel, The Syndic, published in 1953. It posits a future in which governments have collapsed under their own weight of bureaucracy and been replaced by the Mafia. In 1953, it was far-out whimsy. How would an Eastern European read it today? The real pleasure in reading Kornbluth is that his sharp satire is delivered in a crisp, purely colloquial style, as if Damon Runyan where writing sociological Science Fiction. A serious writer, today, would make heavy going of this stuff, stretching it out and filling it with stylistic tricks and learned references. Kornbluth wrote like an experienced barber.… a few deft strokes with a very sharp blade, done like magic, and over before you can catch your breath. Fifty-three years have passed since this novel hit the stands, and it is not quaint. It’s still a good, clean shave.

A fine introduction to Kornbluth’s work would be this novel, The Syndic, published in 1953. It posits a future in which governments have collapsed under their own weight of bureaucracy and been replaced by the Mafia. In 1953, it was far-out whimsy. How would an Eastern European read it today? The real pleasure in reading Kornbluth is that his sharp satire is delivered in a crisp, purely colloquial style, as if Damon Runyan where writing sociological Science Fiction. A serious writer, today, would make heavy going of this stuff, stretching it out and filling it with stylistic tricks and learned references. Kornbluth wrote like an experienced barber.… a few deft strokes with a very sharp blade, done like magic, and over before you can catch your breath. Fifty-three years have passed since this novel hit the stands, and it is not quaint. It’s still a good, clean shave.